NASA has pulled off the first powered flight on another world. Ingenuity, the robot rotorcraft that is part of the agency’s Perseverance mission, lifted off from the surface of Mars on April 19, in a 39.1-second flight that is a landmark in interplanetary aviation.

“We can now say that human beings have flown a rotorcraft on another planet,” says MiMi Aung, the project’s lead engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Ingenuity’s short test flight is the off-Earth equivalent of the Wright Brothers piloting their aeroplane above the coastal dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. In tribute, the helicopter carries a postage-stamp-sized piece of muslin fabric from the Wright Brothers’ plane. “Each world gets only one first flight,” says Aung.

The flight came after a one-week delay, because software issues kept the helicopter from transitioning into flight mode two days ahead of a planned flight attempt on April 11. Today, at 12:34 a.m. US Pacific time, Ingenuity successfully spun its counter-rotating carbon-fibre blades at more than 2,400 revolutions per minute to give it the lift it needed to rise three metres into the air.

The $85-million drone hovered there, and then, in a planned manoeuvre, turned 96 degrees and descended safely back to the Martian surface. “This is just the first great flight,” says Aung.

Four further flights, each lasting up to 90 seconds, are planned in the next two weeks. The next one is tentatively scheduled for April 22. In it, Ingenuity will aim to rise five metres above the surface, fly laterally for about two metres, then fly two metres back and land at the same place it took off.

Eventually the helicopter may fly faster and farther, travelling up to 300 metres from its take-off point. Each successive flight will push Ingenuity’s capabilities to see how well the drone fares in Mars’s thin atmosphere, which is just one per cent as dense as Earth’s.

“We will be pushing the envelope,” says Aung – probably to the point that Ingenuity will ultimately crash, by design.

Space agencies have sent drifting aircraft to other planets before. For example, the Soviet Union’s Vega One and Vega One missions sent balloons into Venus’s atmosphere in 1985. But Ingenuity’s flight is the first controlled flight on another planet.

“I’m just thrilled with the way it has turned out,” says John Grunsfeld, a former astronaut who approved the Ingenuity programme when he served as NASA’s associate administrator for science.

Ingenuity’s purpose is to test whether helicopters could be used to explore other worlds. As it flies across the terrain, it snaps black-and-white images of the surface below, and colour images looking toward the horizon.

Future helicopters could help rovers, or even astronauts, to make their way across the surface, by scouting for interesting areas ahead and relaying images of what the landscape looks like.

Big rotorcraft could also get into areas that are inaccessible to rovers rolling across the ground, says Anubhav Datta, an aerospace engineer at the University of Maryland in College Park who has been working on Mars helicopter concepts for decades.

“If we are serious about human missions to Mars we should be serious about sending large helicopters to truly explore what awaits there,” he says. “The most interesting places we want to explore are not on flat land but up the slopes, on the cliffs, down the craters and into the caves.” Cameras and other instruments aboard helicopters could capture information about such places.

NASA is already building a car-sized octocopter named Dragonfly that it plans to send to Saturn’s moon Titan. Set to launch in 2027, the copter would explore Titan’s atmosphere, which is four times denser than Earth’s and is rich in primordial organic compounds. That’s a very different environment from the one that Ingenuity is experiencing on Mars.

But the early flight lessons from Ingenuity will inform Dragonfly’s design. “We’re looking forward to learning from the Ingenuity team’s experience flying in an extra-terrestrial sky,” says Elizabeth Turtle, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, who is Dragonfly’s principal investigator.

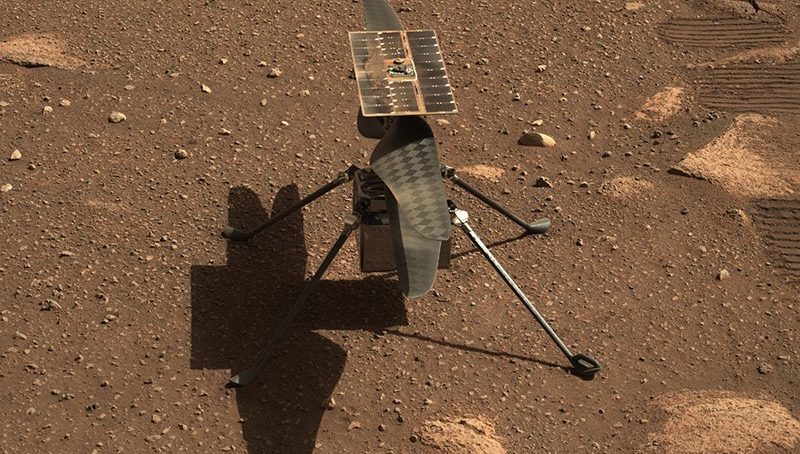

Ingenuity arrived in Mars’s Jezero Crater in February, nestled under the belly of the Perseverance rover. From its landing site, Perseverance drove to a flat ‘airfield’ in the crater that is relatively free of rocks, and deposited Ingenuity there. The rover then rolled to a slight rise 65 metres away, a vantage point from which it watched and videotaped Ingenuity’s first take-off and flight.

The biggest challenge in designing Ingenuity was making it small and light enough to be carried under Perseverance’s belly, while still being capable of flight, says Aung. The helicopter ended up weighing just 1.8 kilograms. Engineers tested it on Earth in a special chamber at JPL from which nearly all the air had been sucked out, to simulate the thin Martian atmosphere.

Compared with a similar-sized helicopter on Earth, Ingenuity has larger blades that spin much faster, to lift it into the thin Martian air. Datta says that he will be anxiously awaiting information on how much power the helicopter takes to hover; this knowledge will help engineers to better understand the aerodynamics on Mars.

Another researcher, William Farrell at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, is crossing his fingers that Ingenuity will help scientists to gain a better idea of the electrical properties of the Martian atmosphere. To do this, it would need to fly – or at least spin its blades – near dusk on Mars.

Farrell and his colleagues recently calculated that the moving helicopter blades could become electrically charged through contact with the dust in the surrounding air, much as helicopter blades on Earth can build up charge in sand storms.

That could cause a faint blue-purplish glow along the blades, best visible in the dim light of dusk. Farrell has asked the Ingenuity team if it could rotate the blades during dusk at some point – and if that happens, he will be watching closely.

The thin Martian atmosphere means that winds there are not particularly strong. Ingenuity can handle winds of a little over 10 metres per second while flying, and stronger winds when it’s sitting on the ground. It is powered by solar panels to keep it warm during the freezing Martian nights, when temperatures can sink to -90 ºC at Jezero Crater.

Ingenuity is designed to last just 30 Martian days, which end on 4 May. After that, team scientists will turn their attention back to the rover on which it travelled to Mars. Ingenuity will rest in perpetuity in Jezero Crater as Perseverance trundles off on its main mission to collect rock samples for eventual return to Earth.

- A Nature magazine report