In the weeks following the October 25 coup there were numerous reports that the military was looking to name a civilian prime minister to head up the military’s refashioned government.

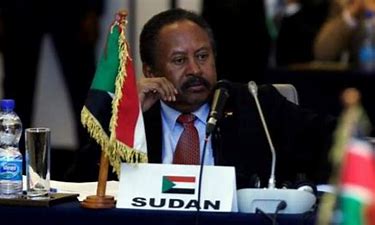

Always high up on the list of candidates was the current transitional prime minister, Abdallah Hamdok, whom the military kept under house arrest while most of the rest of the cabinet and hundreds of other civilian government officials remained in detention.

The November 21 agreement between Lt-Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Hamdok appears to be the culmination of the military’s efforts, thereby creating the appearance of continuity in civilian leadership. Acknowledging that the agreement is not optimal, Hamdok has justified the deal as a way to defuse the political standoff following the coup without further loss of life.

While many details remain unclear, as currently stands, the agreement would represent a validation for the military coup. It would also signify a startling turnabout for the military, which has been facing widespread domestic condemnation, escalating popular protests, and international isolation, including the revoking of aid and debt relief. In fact, it was becoming increasingly apparent that the military could not sustain the coup – politically or economically – and would need to find a way to walk back their extra-legal action.

Public reactions to the agreement in Sudan have been mostly highly critical as it falls short of protesters’ demands for the restoration of the internationally recognized pre-October 25 civilian cabinet, release of all political prisoners detained since the coup, and that civilians take over leadership of the transition process from the military.

Instead, Hamdok appears to have conceded to the military’s demand that the cabinet be reshuffled to one more pliable to the military’s interests. The agreement, thus, reinforces the fundamental obstacle to Sudan’s democratic transition – the military’s sense of entitlement to run the government.

Twelve civilian ministers from the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), a leading civilian coalition, resigned their positions following the deal. All but two ministers from the pre-coup cabinet have now resigned – and those two remain in custody.

Moreover, three-quarters of the FFC Central Committee have refused even to meet with Hamdok. He, therefore, appears to have lost his domestic constituency by signing onto the deal with the military.

Civilians have also contended that the agreement between Burhan and Hamdok lacks a legal basis. The transitional government has been operating from a transitional Constitutional Charter signed in 2019 by the military and leading civilian groups as part of a three-year transition process.

As part of that power sharing deal, the FFC was responsible for appointing the prime minister who would select a cabinet. Furthermore, any amendments to the Charter required the approval of the Legislative Council – or in its absence, the Sovereignty Council and Council of Ministers. Since all these provisions were disregarded, the FFC concludes that the November 21 agreement is between two individuals, not the institutional stakeholders to the 2019 Charter. It consequently lacks both a legal foundation – and legitimacy.

The backbone of the civilian calls for change has been a network of “resistance committees” – grass roots civil society organisations established starting in 2013 to educate the public and advocate for democratic change in Sudan. These diffuse, though well-organised, committees provide a structure to focus and sustain civilian demands for change. Born out of Sudan’s legacy of nonviolent resistance to military and authoritarian rule harkening to the 1964 and 1985 revolutions, these committees represent a distinctive feature of Sudan’s political landscape.

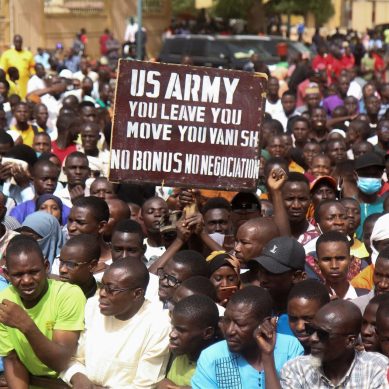

These resistance committees have vowed to continue protesting until they see a genuine restoration of the democratic transition process. Since the coup, many of these committees have called for the total and immediate withdrawal of the military from Sudanese politics.

In short, the Burhan-Hamdok agreement has largely not been viewed as credible by Sudan’s key domestic stakeholders. Instead, it is seen as a means of affirming and legitimising the role of the military in government and Burhan’s position as head of state (a role he assumed but was not authorised under the 2019 Constitutional Charter).

The Burhan-Hamdok agreement raises other fundamental concerns over governance norms in Sudan. Paradoxically, rather than having to make political concessions for mounting the coup, the military would be rewarded for co-opting the democratic transition.

“The agreement, thus, reinforces the fundamental obstacle to Sudan’s democratic transition—the military’s sense of entitlement to run the government.”

Since the October 25 coup, Sudan’s security forces have also been willing to use lethal force on unarmed civilians. According to the Central Committee of Sudan Doctors, many of the more than 40 protesters who were killed by the military were shot in the head or chest.

Security forces, thus, were shooting to kill, not to disperse the protests or protect property. This use of violence speaks to the military’s attitudes toward civilians and public expression. It has also deepened public antipathy for the military, squandering the measure of goodwill that had been established since the democratic transition began in 2019.

Similarly revealing has been the military’s effort since the coup to replace civilian officials with stalwarts from the regime of long-time autocratic ruler Omar al-Bashir. This is significant since the Bashir era had been widely vilified, including by the military, since the 2019 protests.

That the military is now apparently attempting to restore elements of the Bashir administration, including Islamists, suggests an affinity for – and interest in maintaining continuity with – the Bashir era, further exposing the military’s lack of commitment to a democratic transition.

Another revelatory move by the military since the coup has been the firing of the Deputy Governor of the Central Bank, Farouck Hussein, as well as the directors of the Nile Bank, Al-Nile Savings Bank and Industrial Development Bank. These moves have been accompanied by reported pressure on the Central Bank to transfer funds to accounts controlled by the military.

This predatory style of government is another trademark of the Bashir era and is consistent with the military’s heavy involvement in the Sudanese economy, purportedly controlling some 250 businesses.

So, where does this leave Sudan’s democratic transition? As with all coups, Sudan is on shaky legal ground. The constitutional basis of the Sovereignty Council was established by the 2019 power sharing agreement. Since Burhan dissolved the Sovereignty Council and other transitional governing bodies in his October 25 takeover, his authority as the transitional leader of the Council has also been rescinded.

His claim to authority now comes solely from the barrel of a gun. As with other coups, what now is lawful is, effectively, whatever the military says it is.

The same logic applies to the trajectory of the transition. Unfortunately, all indications are that the military was never that serious about a genuine transition.

Instead, its objective seems to be to maintain a principal governing role for the military in Sudan, a posture it has held for all but 10 years since independence in 1955. Moreover, as we’ve seen in other coups in Africa over the past year, militaries have limited incentives to lead democratic transitions.

“The Sudanese public has thus far demonstrated that they will not accept the new governing arrangement, despite Hamdok’s reinstatement as prime minister.”

- A Tell /ACSS report