Mubarak Nur, an Afar teenager who stuck out the rebel occupation in Abala in northern Ethiopia, recalls the looting and killings his home town witnessed.

Nur recalls, “[The Tigray forces] did what you can see. They looted everything when they entered: blankets, food, wheat, vehicles. They also killed some people here. I saw them shoot one person.”

Another Afar resident from Abala, Mohammed Idriss, said several people were killed by Tigrayan rebel forces as they fired from the mountain escarpment that towers over the town.

“I saw five people I know, including two Tigrayans, killed by heavy machine gun fire,” he said. “Their bodies were divided into pieces; I saw this with my own eyes. Many Afar and Tigrayans were killed when they fired into the town.”

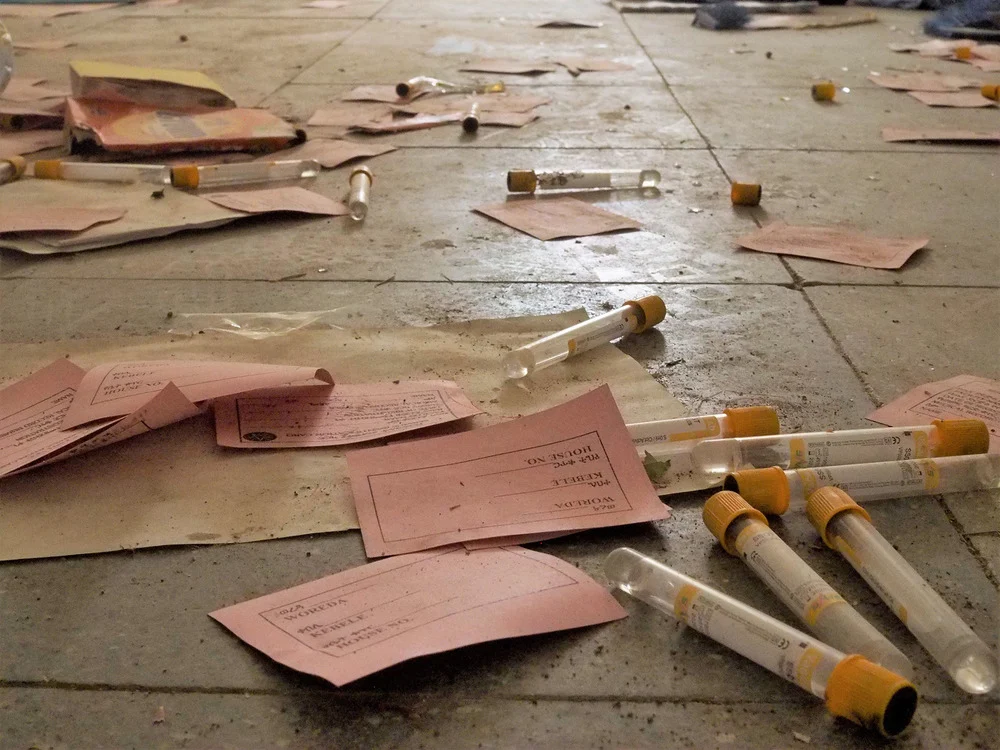

The nearby town of Erebti, a short drive from Abala, was also occupied by the TPLF after they entered the Afar region. The compound of its main government office was littered with broken computers and desk chairs when we visited last week, and the outer wall of the main building was adorned with the slogan: “Tigray shall be victorious.”

Since the TPLF left Abala and other parts of Afar, there has been a lull in fighting across Ethiopia. On March 24, the federal government declared a “humanitarian ceasefire”. The Tigray rebels responded by saying they would observe a “cessation of hostilities”.

The situation, however, remains tense. Afar fighters have set up ad hoc checkpoints close to the frontline and the UN official who asked not to be named, said their team was shot at recently by local militia while driving near Abala.

There has been a fair amount of sabre-rattling from both sides since the truce came into force, as well as reports of renewed clashes between the TPLF and Eritrean troops in northern Tigray; but for the most part it appears to be holding. It has been bolstered by a series of high-level talks between military commanders from both sides, mediated by the African Union.

This led to the TPLF’s withdrawal from Afar in late April. Since then, restrictions on aid entering Tigray have eased.

Between June 2021 and up to April 1 this year, virtually no aid reached Tigray, whereas roughly 1,000 trucks have arrived in Mekelle, the region’s capital, in the past two months. All passed through Abala – a key choke point, before entering rebel-held territory. The vehicles form long lines outside Semera as they queue for customs clearance.

Banking services, road links and communications are still cut. However, and many more trucks need to enter Tigray to meet the region’s needs. The United States has warned that 700,000 people could face famine, and Mekelle’s main Ayder Hospital has been forced to close.

“There is no power, medical supplies, or oxygen,” a doctor at the hospital told The New Humanitarian by phone, adding that all patients, except emergency cases, have been sent home and no new ones are being admitted. “We don’t know what will happen to them,” the doctor said. “If they are critical, they will die.”

Last week, the petrol station next to the World Food Programme’s warehouses in Semera was full of truck drivers stocking up on supplies for the long drive to Tigray. One driver, who was smoking a cigarette in the forecourt, described witnessing poor conditions in Mekelle.

“There are a lot of beggars and everything is expensive,” he said. “There is no beer, water or soft drinks to buy.”

Yet foreign diplomats in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, are hopeful the resumption of aid will build confidence and pave the way for proper negotiations. One, speaking on condition of anonymity, said both sides appear serious about “giving peace a chance” after months of fighting.

Many issues are yet to be resolved. The most glaring is the fate of western Tigray. It is under the occupation of regular and irregular Amhara forces – accused by rights groups and the US of conducting a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the area’s Tigrayan population.

Any concessions from the federal government over western Tigray would be deeply unpopular among the Amhara, Ethiopia’s second biggest ethnic group, whose eponymous home region was the site of heavy fighting last year.

Last month, amid bubbling discontent in the region, Amhara security forces launched a crackdown against militia groups opposed to the ceasefire – even though they had played a key role in repelling the TPLF as it advanced towards Addis Ababa in November. So far, at least 4,000 people have been arrested.

Meanwhile, the 300,000 residents of Afar displaced by the conflict face an uncertain future. Mohammed Hussein, the head of the region’s aid office, said there aren’t enough funds to rebuild, and the local government is struggling to get humanitarian supplies to those who need them most.

“We are deploying the resources we have as a region,” said Mohammed. “But right now, it is beyond our capacity to address each and every need.”

Some ethnic Afar are starting to return to Abala. At a small camp of huts made from sticks and plastic sheets pitched by a dry riverbed just outside the town of Erebti, Kulsuma Faya said her family had been on the road for several months.

A few hours before she was interviewed, one of the children from the camp – a one-year-old girl called Madina – had died from an infection.

“We are angry because we didn’t receive any help so far. We have no food, no water,” said Kulsuma. “One of the children just died. The men are burying her now.”

“The main thing we need is to return home,” she added. “But we don’t know if we can. Everything there is destroyed.”

- The New Humanitarian report