The risk of death by suicide in the United States is higher when guns are easily accessible in a home, research finds. However, keeping firearms unloaded and locked away in homes resulted in a decreased suicide and homicide incidence in the past five years, according to the findings.

This was the outcome of an undertaking by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded project in which paediatricians counsel parents about ways to limit gun access by keeping firearms unloaded and locked away in their homes.

Sandy Hook set the stage for federal funding to open up, says Nina Vinik, a former programme director and now a consultant at the Joyce Foundation. Among the numerous efforts to push for gun policy, “advocates saw that the case for federal funding for research was just an easy one for people to understand and get behind”, she says.

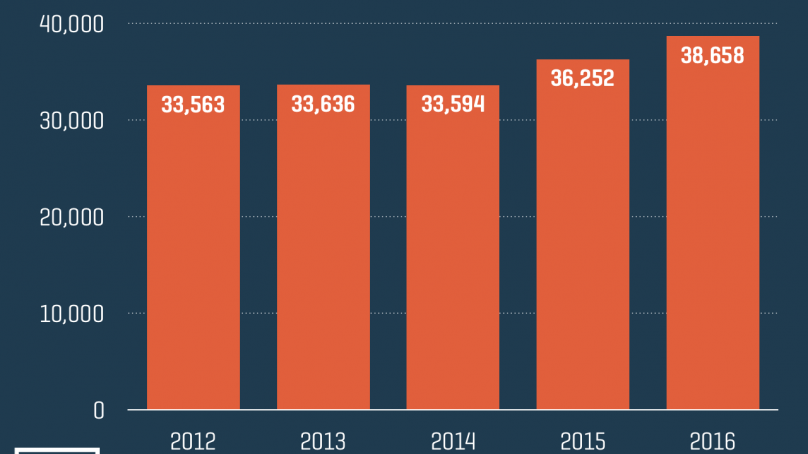

Funding figures bear this out. According to data provided by NIH, between 1996 and 2015 the agency spent just under $2 million per year on average on research related to firearms. A new analysis by Nature estimates that the average more than tripled to just over $6 million per year over the next four years.

Then, in February 2018, a shooter in Parkland, Florida, killed 17 people at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and injured 17 others before police arrested him. A national firestorm erupted over gun-control policies alongside renewed advocacy for research funding.

The next month, lawmakers added language to the annual budget legislation that clarified the conundrum posed by the Dickey Amendment, stating that “the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has the authority to conduct research on the causes of gun violence”.

Lawmakers eventually authorised dedicated funding in December 2019, giving $12.5 million each to the CDC and the NIH specifically for gun-violence research. Congress approved a second round of funding for the 2021 fiscal year in December and President Biden in his budget request for 2022 asked for $50 million to go to the agencies.

In March 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic looming, the NIH put out a call for projects seeking to study public-health questions related to gun violence.

Wallace at Tulane was one of nine researchers funded through the mechanism. She says that her research on gun laws could have direct relevance to policy. Gathering evidence that rules in some states reduce deaths for pregnant people could persuade other states to enact similar measures. That would be huge, Wallace says, because it “identifies a policy that states can pass now and have an immediate impact”.

Lisa Wexler, a community-based participatory researcher at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also answered the NIH’s funding call. She was looking for ways to involve families in her work to prevent suicides in rural Alaska.

During the 1990s and 2000s, Wexler worked there as a mental-health counsellor and a community organiser, and saw the crisis faced by Alaska Native youth. Alaska’s Indigenous people are twice as likely to die by suicide as are non-native residents of the state, and it is the leading cause of death for Alaska Native men under the age of 24.

She and her collaborators at the Maniilaq Association, an Alaska Native non-profit organisation in Kotzebue that provides health services to Northwest Alaska residents, are laying the groundwork to test a new approach to gun safety. At health clinics, they will give people a brief talk about the need to safely store firearms at home, and offer them a lockable ammunition box or the option to have someone install a gun cabinet.

“Making the environment safer is incredibly important, and it’s sort of an overlooked part of what we need to be doing for suicide prevention specifically in this country,” says Wexler. Past studies have shown that limiting access to lethal means correlates with a decline in suicide rates.

Wexler’s programme, by involving all residents, acknowledges the Alaska Native values of community support and belonging – as well as the ubiquity and necessity of gun ownership in the region.

A Los Angeles police officer throws assault rifle into a garbage container on the street during an anonymous gun buyback event

“Hunting and fishing and gathering and living close to the land and animals and sea is still very deeply ingrained in the region here,” says Arlo Davis, Family Safety Net coordinator at the Maniilaq Association, who works with Wexler. “Our challenge is how do we do this research without shaming anybody – because most households have guns.”

Any shift in suicide trends will take some years to see, Wexler says, but she hopes such an approach will be one way to reduce the death toll. Across the country in Philadelphia, implementation scientist Rinad Beidas at the University of Pennsylvania is testing whether routine paediatric visits can be an effective time to talk with new parents about gun safety.

Like Wexler, Beidas hopes to prevent suicides – the risk of death by suicide is higher when guns are easily accessible in a home. Her NIH-funded project will have paediatricians counselling parents about ways to limit gun access – for instance, by keeping firearms unloaded and locked away in their homes – alongside the conventional checklist of child-safety measures, including car seats and smoke alarms. Study volunteers will also receive locks for their guns from the programme.

“Just like we made cars safer with seatbelts, we want to make homes safer around safe firearm storage,” she says.

All told, the NIH disbursed about $8.5 million to nine new proposals in 2020, short of the $12.5 million authorized by Congress. The agency attributes the shortfall to the timing with the pandemic: “We did not receive as many applications to the [Funding Opportunity Announcement] as we would have liked,” a spokesperson for the NIH told Nature by e-mail.

The agency applied the remaining money, plus another $1.5 million, towards 12 other projects that included firearm research as an aspect of their proposal, for a total of about $14 million.

Branas served on review committees evaluating research applications for both the NIH and the CDC, and says that, despite the low number of applications specifically to the gun-research call, he was encouraged by the responses. “We felt like maybe there was some kind of pent-up interest in the topic, and people just didn’t have an outlet to apply.”

At the CDC, 18 research projects received just over $8 million for multi-year studies. The CDC also spent $2.2 million on an effort to gather data on emergency-room visits for non-fatal firearm injuries in 10 states. The appropriation for this fiscal year will be used to fund the existing projects.

“It was incredibly gratifying and important to receive this funding,” says James Mercy, director of the Division of Violence Prevention at the CDC’s Injury Center. “We’ve been operating for almost 25 years not being able to fully address the role of firearms in violence.”

It’s not yet clear whether the available funding levels will be sustained or expanded. One theme could be key to keeping bipartisan support for funding, says Mark Rosenberg, who led the CDC’s Injury Center at the time it was facing heat from Congress in 1996. In his view, more projects should be studying the impact that regulations have on those who own guns legally, because policy is often stymied by the perception that safety measures serve only to restrict rights.

“I don’t know yet how to measure it effectively, but until you measure it, people will be free to say that any law impinges too much on the rights of law-abiding gun owners.”

Some watchers are hopeful that the funding levels will increase, even if they don’t hit Biden’s target of $50 million annually. “We’ve opened the door now and I don’t see it closing,” says Vinik. State governments seem to have momentum as well: lawmakers in California, New Jersey and Washington state, among others, have allocated funds for researching violence prevention and safety.

But what’s still missing, researchers say, is federal support to tackle big, expensive, basic questions. For instance, nearly 40 per cent of US households have a gun, and most people buying one say it’s for protection. But the limited data that are available suggest that homes with guns are not safer, says Studdert.

“That’s a very fundamental disconnect between the admittedly somewhat modest science we have in this area, and the perspectives of most gun buyers in the United States.”

Community organisations have for decades created and used violence-prevention techniques, but they have not been tested with field surveys. “Some of them probably work, some of them probably don’t. But we need the research to identify the ones that work and the effective ingredients in those programmes,” Morral says. “And that’s expensive.”

Morral and others think that more investment will be needed to fully address the public-health issue that guns present in the United States. An analysis commissioned by Arnold Ventures and the Joyce Foundation, published this month, estimates that meeting public-health data collection and research needs on this topic will cost between $587 million and $639 million in federal funding over five years. That’s a big gap. “Twenty-five million is a pittance,” Branas says. “We need at least another zero at the end of that.”

- A Nature report