Despite shortcomings, Kenyans have set a new and higher electoral bar for themselves, their neighbours, and the rest of Africa – demonstrating how closely contested elections can be credibly resolved through sufficiently independent institutions.

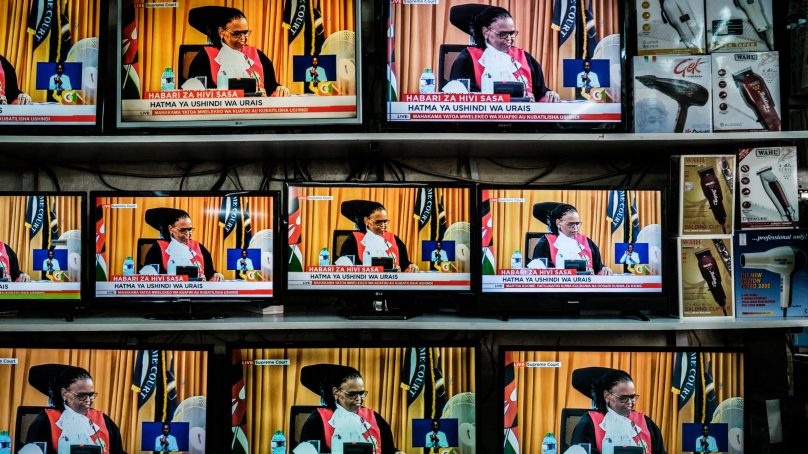

Kenya’s Supreme Court has upheld the results of the August 2022 presidential election affirming that Deputy President William Samoei arap Ruto will be Kenya’s fifth president. Ruto garnered 50.5 per cent of the vote versus Raila Odinga’s 48.9 per cent – a difference of 233,000 votes out of more than 14 million cast.

Most distinctively, the electoral process was conducted in a markedly more transparent, competitive, and democratic climate than any previous Kenyan election. Understanding the factors that contributed to this higher standard, therefore, is vital to normalising these measures – in Kenya and elsewhere in Africa.

1. Independent Monitoring Enhances the Legitimacy of the Outcome

The results validated by the Supreme Court were widely accepted, in part, because they were corroborated by the Nairobi-based Elections Observation Group (ELOG), Kenya’s largest election monitoring coalition. Its parallel vote tabulation (PVT) produced almost similar results to that of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) with a margin of error of between 0.1 and 2.1 per cent.

ELOG deployed 5,000 observers in all 47 counties, covering 47,000 polling stations. An additional 1,000 PVT monitors crunched incoming data from the IEBC portal in real time.

Complementing the PVT, for the first time in Kenya – and possibly Africa – IEBC data released from the polling stations was accessible to the public. This allowed Kenyan media to run their own tallies and release provisional results 72 hours before the IEBC.

Armed with this data, they also provided 24-hour analysis of the polls, setting a new norm worth emulating. The steady stream of data allowed the political parties, civil society organisations, and ordinary citizens to concurrently track the unfolding results.

In other words, the public was kept informed of the seesaw nature of the contest and the factors that were shaping the outcome – facilitating its credibility.

2. Candidates Set Tone by Disavowing Violence

To their credit and despite the tight race, both leading candidates showed restraint from invoking their supporters to violence during the electoral process. Raila Odinga, in particular, demonstrated leadership and a commitment to the democratic process when, in the days after the election results were announced by the IEBC and his supporters were ready to take matters into their own hands, he said he would take his case to the courts.

Rather than opting for violence to enhance his leverage or distract from the electoral math, he told his partisans to go home while he worked through the judicial system. Odinga invoked the same principle by accepting the court’s unanimous verdict, even though he disagreed with it. This courageous leadership must not be taken for granted. Kenyans of all political persuasions should honour this act of public service where the interests of the nation are put ahead of those of the individual. It is a standard to be upheld in future elections.

“Rather than opting for violence to enhance his leverage or distract from the electoral math, Odinga told his partisans to go home while he worked through the judicial system.”

Similar acts of political magnanimity were observed down the ticket. Concession speeches by those who lost gubernatorial or local races, similarly, came in early and often. This created what Kenyan political commentator Patrick Gathara called “an un-Kenyan election,” a sharp contrast with previous elections that were filled with glaring malpractices.

3. The Courts Can Be a Force for Stability

“Beginning with the adoption of a new constitution in 2010, Kenya has slowly and purposefully been reinventing itself and its democracy,” says Patrick Gathara. He contends it also demonstrated a high degree of democratic maturity as Kenyans opted to litigate their differences over the election, rather than resort to force.

Much of this heightened trust in the courts can be traced to the 2010 Constitution which strengthened the independence of Kenya’s judiciary and other oversight institutions. Odinga’s decision to pursue legal channels to address his grievances was motivated, in part, by a renewed sense of confidence in the judicial system. For courts to play a similarly stabilising role across Africa, this judicial trust must be earned, however.

A pivotal step in this evolution of judicial independence was the historic Maina Kiai Petition of 2016, a civil society-led petition introduced ahead of the 2017 election by legal scholar Maina Kiai.

In agreeing with it, the High Court issued a ruling that overhauled Kenya’s electoral laws by introducing ground-breaking standards of transparency, ownership, integrity, and accountability – the outcomes of which were visible in the recently concluded polls.

Among other changes, the Court ruled that election results at each polling station are final and cannot be altered in any way. This overturned the practice of vesting sweeping powers in the IEBC chair to alone “confirm, alter, vary, and/or verify the presidential election results.”

The Kiai Petition was upheld in its entirely in August 2017 by the Court of Appeals, Kenya’s highest court, rejecting a government appeal. The Supreme Court decision to overturn the 2017 elections was based on this petition.

While doubts over the autonomy of Kenya’s judiciary persist, with many Kenyans saying at least some of the country’s judges are corrupt, Kenya’s upper courts have painstakingly established institutional traditions of independence irrespective of their composition.

Supporters cite the March 2022 landmark Supreme Court ruling that declared the controversial Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) illegal and promptly stopped the government-backed referendum that would have endorsed it.

This initiative would have brought back the “imperial presidency” model of the Daniel Arap Moi era, which the 2010 Constitution abolished.

Another benefit from the enhanced transparency of the electoral process is that the Supreme Court will continue to be under heightened scrutiny in future elections. Since the public had access to all the IEBC polling data, citizens are in a better position to assess the court’s performance than they have been in the past.

A Tell / Africa Institute of Security Studies / Paul Nantulya