Kenyans have carved out a roadmap for themselves and democratic reformers across the continent, experts say. The country’s 2022 General Election has not followed the familiar script of voters exercising their civic duty only to helplessly sit back and watch their votes be manipulated.

As work-in-progress, Kenyans have attempted to correct this through comprehensive constitutional reforms, an active and vigilant citizenry, and an increasingly independent judiciary.

In the process, Kenyans have carved out a roadmap for themselves and democratic reformers across the continent to follow to enhance the integrity and legitimacy of their electoral processes.

In a report, the Africa Institute of Security Studies says, “Rather than opting for violence to enhance his leverage or distract from the electoral math, Odinga told his partisans to go home while he worked through the judicial system.”

The second instalment of the report looks at three other takeaways from the election that has many lessons for African governments and judiciaries to borrow from.

1. The need to Further technocratise the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC)

The election was not problem-free, to be sure. In their petition, Odinga’s Azimio La Umoja party alleged that the IEBC bungled the verification of results from the polling stations, especially during the final stages of tallying.

Four of the seven IEBC commissioners, including Deputy Chair Juliana Cherera, disowned the results moments before they were released on August 15 by IEBC Chair Wafula Chebukati. The dissenting IEBC commissioners say they were excluded from verifying and aggregating results.

According to Cherera, “We [IEBC] have improved our processes…we upped the bar but there was opaqueness in the last phase.”

This points to a key area for further reform. Leading jurists are now debating how the problems that beset the final phase of the election might be addressed. One recommended fix is to expand the provisions of the Maini Kiai Petition.

Kiai observes that his eponymous petition can be improved by empowering the polling stations to announce their results after capturing them on the hardcopy Form 34 A, the primary record of Kenya’s polls.

“With hindsight, there is still room for manipulation because anything can happen during the electronic transmission of Form 34 A to Nairobi for verification. Think of it, why should the final results be verified away from their source? It leaves room for the kind of disputes we saw within the IEBC itself.”

Kiai adds that manual entry of results at the polling station need not be electronically transmitted for “verification” in Nairobi. “We have learned with hindsight that electronic transmission can be manipulated even in more perfect settings. We are looking at a few external precedents that can be written into our electoral laws such as the Netherlands which reverted to manual entries across the board” to safeguard against potential foreign interference.

“Enhancing the technocratic dimensions and strictures on the IEBC may also lead to a more secure environment for election workers.”

Enhancing the technocratic dimensions and strictures on the IEBC may also lead to a more secure environment for election workers. Chairman Chebukati lamented that his senior staff and commissioners had faced intimidation, threats, arbitrary arrests, and enforced disappearances during the tallying.

A chilling illustration of this was the murder of senior IEBC officer, Daniel Mbolu Musyoka. He was abducted from a tallying center in the battleground of Embakasi on August 11 as he prepared to announce results.

Two days later his body was found dumped near a forest with signs of torture and strangulation. Deputy Chair Cherera, similarly, has alleged multiple threats against her.

Kenya’s security services are facing pressure to investigate these and other serious complaints—a stark reminder of the still unfinished work Kenyans face to consolidate their hard-earned democratic gains.

2. Ethnicity need not define voter motivations

Contrary to widely held expectations, Kenya’s largest and most economically influential community, the Kikuyu, voted overwhelmingly for William Ruto, a Kalenjin, handing him a victory in his rivalry with Uhuru Kenyatta, his former close ally of over 20 years. This is significant given the fresh memories of the infamous 2007 polls, when elite rivalries among both communities and the Luo, from which Odinga hails, exploded into bursts of violence that brought Kenya to the brink of civil war.

In turning up for Ruto this time around, Central Kenyans also effectively repudiated the powerful Kikuyu Council of Elders—the region’s unofficial but powerful kingmakers—who told their followers to vote according to wishes of the Kenyatta family.

Notably, Ruto secured landslides in the home constituencies of President Kenyatta and Odinga’s running mate, Martha Karua – one of Central Kenya’s most formidable politicians. According to Kenyan political scientist Macharia Munene, “people are turning away from that [ethnicity], saying they are no longer going to be taken for granted.”

To illustrate this, both Ruto and Odinga ate aggressively into their respective strongholds, pockets of which became fiercely contested battlegrounds – far from the “safe zones” they had been assumed to be. Simply put, the old politics of undisputed ethnic kingpins and dominant political families seems to have lost resonance among Kenyan voters.

6. Incumbent presidents do not always secure their preferred successor

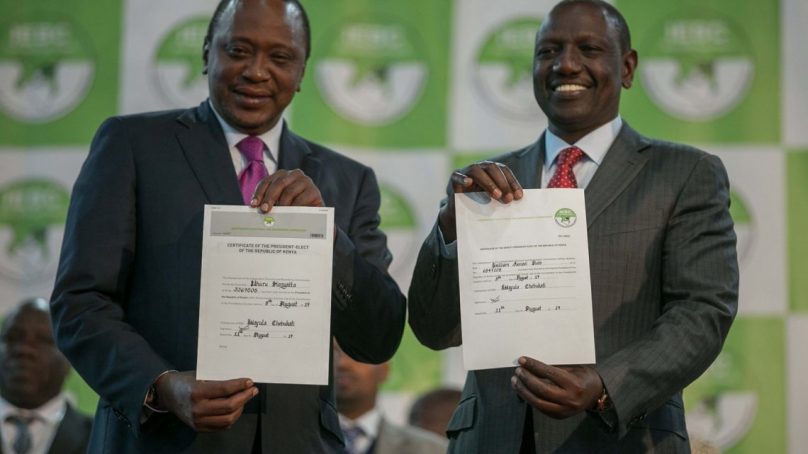

Raila Odinga’s loss has been widely interpreted as a major humiliation for President Kenyatta. Kenyatta had thrown his weight behind Odinga following their “handshake” in 2018 that put their enmity aside and further isolated William Ruto.

Some say that the voting patterns were an attempt by voters to hold Kenyatta and Odinga accountable for trying to institute BBI, an initiative that proved to be hugely unpopular.

Others say the Odinga brand was invariably damaged as the Ruto ticket pushed a narrative that the veteran opposition leader was merely Kenyatta’s “project.”

This harkened back to the equally consequential election of 2002 in which a younger Kenyatta, then President Daniel Arap Moi’s hand-picked successor, garnered only 31 per cent of the vote in what turned out to be a massive opposition landslide against the regime. His portrayal as “Moi’s project,” proved to be a major liability as even his own constituency channeled its votes to the opposition.

Kenya’s increasingly unpredictable and competitive elections buck the general trend in the region where predetermined electoral outcomes and poll-fixing are the often norm.

3. Sustained civic engagement on institutional reforms can have a strategic impact

Ruling parties in much of Africa often go to great lengths to keep electoral commissions on a tight leash to maintain themselves in office. In Kenya, the ongoing shifts toward more credible elections were rooted in sustained public interest litigation aimed at breathing new life into the IEBC and bringing electoral laws in line with constitutional requirements.

The tenacity and forward-thinking by civil society and professional groups – particularly the Law Society of Kenya – was key to all this, as shown by the history of ground-breaking constitutional petitions dating back to the 2017 elections.

This, in turn, benefited greatly from a judicial branch that has demonstrated an increasing willingness to assert its independence and rule in the public interest. Collectively, these advancements underscore the value of institutional reform, as painstaking as the process may be.

“Kenyans have carved out a roadmap for themselves and democratic reformers across the continent.”

Kenya’s 2022 general election has not followed the familiar script of voters exercising their civic duty only to helplessly sit back and watch their votes be manipulated. Kenyans have attempted to correct this through comprehensive constitutional reforms, an active and vigilant citizenry, and an increasingly independent judiciary.

In the process, Kenyans have carved out a roadmap for themselves and democratic reformers across the continent to follow to enhance the integrity and legitimacy of their electoral processes.

A Tell / Africa Institute of Security Studies / Paul Nantulya