Today, post-Saudi Arabia takeover, the question is how and where Newcastle United could accommodate crowds of 60,000-plus. Hemmed in architecturally at St James’ Park, Newcastle might need to move to grow.

Compared to 2019, it feels the club are preaching to the convertible, yet last week Newcastle United Supporters’ Trust concluded a survey in which 73 per cent of respondents said their preference was to remain at St James’ “with renovations”. Only 19 per cent said they wanted to move.

The Trust’s Paul Karter was unsurprised: “We’re a one-club city and I think the tradition and love of having a city-centre stadium is huge in the eyes of Newcastle United fans. There’s heritage there.

“But it’s difficult. It’s a small city, there’s not a huge amount of space.”

Heritage sells, that is obvious from the outside interest in English football. Newcastle United want to be global, but the club does not have the enormous benefit of being in London. Half an hour in Spurs’ club shop reveals an endless number of Korean fans whose spend-per-head is significant. There is a small Australian range, too, at the club managed by Ange Postecoglou, where the famous Tottenham cockerel motif is replaced by a kangaroo.

Newcastle are joining Tottenham on an end-of-season trip to Australia to keep ‘exporting the brand’, but northern English provincial infrastructure is another hurdle – there are, for example, no direct flights from Newcastle airport to the United States.

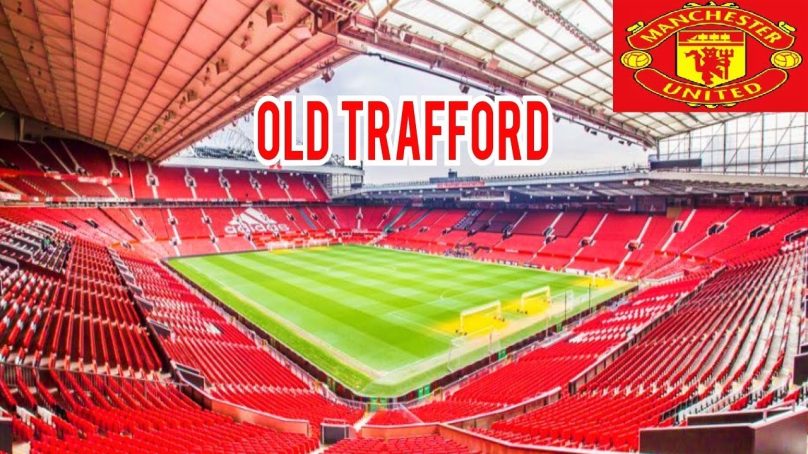

Infrastructure and cost affect Sir Jim Ratcliffe as he enters Old Trafford. Manchester United’s first aim is to establish funding for a redevelopment or a new development, then design and submit a planning application. It could be 2028, 2029 or 2030 before a spade is in the ground.

In the 20 years since Arsenal began demolishing existing premises on the Ashburton Grove site, there has been an escalation in the prices of core materials. According to figures from the Building Costs Information Service (BCIS), one cubic metre of ready-mix concrete in 2004 cost on average £63. By 2014, it was £98, while today it is £136, a 40 per cent increase in 10 years.

One tonne of high-tensile steel bars has risen from £333 in 2004 to £638 in 2014 to £1,200 in 2024 – an increase of 88 per cent in the past 10 years. One tonne of structural steel has gone from £720 in 2004 to £1,075 in 2014 to £1,706 in 2024 – up 130 per cent in 20 years.

A new Old Trafford is likely to be over £1 billion, maybe double, and debt is a loaded word at the club. Given Real Madrid said recently they will not pay off the vast restructure of the Bernabeu stadium until 2053, United’s repayments could go on until the 2060s.

Chris Rumfitt, of the club’s Supporters’ Trust, says at least Ratcliffe’s presence “means there’s a bit more trust – if it had been the Glazers proposing this, we would not trust them to do it right”.

The trust has a voice on the task force set up to address the next step. It had its first meeting last week. The trust has independently conducted its own surveys, asking supporters about priorities rather than the move-or-stay question.

“We thought the best place to start was with, ‘What do we want from the stadium?’” Rumfitt says. “Once you work that out, it maybe leads to the conclusion of the million-dollar question.

“The answer is that opinions are really mixed. There’s a great desire to understand the options and the consequences during the process. We have 55,000 season-ticket holders and, if at any point during work, capacity dropped below that number, then it’s obviously an issue.

“Then, if we did build a new stadium, what would it look like and where would it be? What do we mean by ‘next door’? Would we be looking to be on the same land in the way the Spurs stadium is adjacent to White Hart Lane? Given the amount of available land around Old Trafford, it’s doable.

“Football fans are conservative animals and, yes, everybody fears what could be lost. That’s the argument against a new stadium. The biggest fear is the creation of a generic, soulless, identikit bowl.

“That said, the new stadiums have got a lot better. I think Arsenal are a bit of a victim of the fact they went first. A lot of lessons have been learnt since about designing for atmosphere. Tottenham has it, I haven’t been to the Atletico Madrid stadium but I’m told it is similar, designed to prioritise atmosphere.”

An example of what does not work, Rumfitt argues, is West Ham at the Olympic Stadium, although the owners can point to the beneficial economics of the deal and the fact they have won a trophy since taking residence in 2016.

“West Ham is fundamentally not a football stadium,” he says, “and if you’re in the back section of the away end, you might as well watch it on the telly. It’s appalling. Upton Park and the horrible but brilliant atmosphere was one of the few places that remained genuinely intimidating. West Ham lost so much when they left.”

The Theatre of Dreams is quite a title to behold in this context. There is pressure. As Phillips of AST says: “Moving to a new ground is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get things right.”

Once you have walked through the last of the 2,000 doors at the Emirates or past the ‘H’ fine dining area at Tottenham or emerged from the red lighting of Old Trafford’s home dressing room, you end up high in the Milburn Stand at St James’, scanning a pitch that has been played on since 1880. It has never moved or been rotated.

It is surprisingly moving to think of Newcastle’s early greats such as Andy Aitken or Colin Veitch playing here. What was their view? What do footballers see now? What are their priorities in a stadium? Does anyone ask?

Andros Townsend was running down the wing for Luton that day at Tottenham. Previously, he had run down it for Spurs at White Hart Lane, for Newcastle at St James’ and for Everton at Goodison, among others. Townsend, 32, noted the size of the Tottenham Hotspur stadium and of the pitch – five metres longer and one metre wider than White Hart Lane.

He says players are so focused on matchdays that, practical matters aside, little invades their peripheral vision – although “the size of the away dressing room matters to players” and he laughs when mentioning the quality of the shower gel.

“It was probably a lot more light, more colourful, more things going on,” he says of the new stadium compared to White Hart Lane, “but ultimately in your mind you’re thinking about so many things to do with the game, you’re not really focused on the broader picture, if that makes sense.”

Some managers have said they have never seen a crowd score a goal, but can fans and grounds impact a result?

“Oh, yeah, of course,” Townsend says. “The older stadiums tend to be right on top of the pitch and tend to generate a better atmosphere. I remember White Hart Lane did that, Selhurst Park, now at Luton. Whether that’s a psychological thing or a fact, I don’t know.

“Selhurst Park, especially on a night game, the atmosphere was incredible. Kenilworth Road is one as well. As an opposing player, probably Anfield. This season we were 1-0 up going in at half-time. We concede early in the second half, it’s 1-1 and all of a sudden the crowd just came alive and their players fed off that. It was suddenly tough for us to play out and we ended up losing 4-1.

“St James’ Park for similar reasons. I went there for Everton a few years ago and they were at it. The atmosphere was so intense we could not play out. Their players were on us because they were pumped up by the crowd. Fans’ intensity can transmit itself to the players, without a doubt.”

Luton have their own new stadium plans, but it would be an emotional wrench to leave Kenilworth Road. It sounds unrealistically romantic: can a football stadium have soul?

“One hundred per cent, one hundred per cent,” Townsend replies. “Goodison Park – Everton need to leave Goodison Park because they have had so many financial issues – but Goodison Park, it has so much history, so much memory.

“It’s obviously tough to leave, but in this day and age, it has to be done. Newcastle, again it’s the revenue. Will Newcastle have to sell players because of FFP? Moving to a bigger stadium, you get to sign more players. Do you look at it from a business point of view or a romantic point of view?

“My question to you is: if Spurs were still at White Hart Lane, would they be one of the ‘Big Six’? Would they be in the top four? Probably not. Yes, everyone would have loved to have stayed at White Hart Lane, but when you see the money now, there’s one club never brought up in FFP or profit and sustainability terms – Spurs. Yes, they’ve lost a lot, but they’re a big club because they’re producing big revenues and are able to spend big.”

As a modern player who has experienced old grounds, what would his advice be to those designing a new stadium?

“You have to try to keep the element of fans being close. Look at West Ham and the running track around the pitch, that probably takes away from the atmosphere.

“If you can create new and hostile, that’s win-win.”

Arsenal, at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium on Sunday, and City, who visit in a fortnight, may experience both.

- The Athletic report