It is approaching 6.30pm on a Saturday, a full 90 minutes after the final whistle has blown. At most grounds, the seats and concourses will have been cleaned and swept and long been empty. Only a few stewards would remain to lock up.

Upstairs at the Goal Line Bar at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, however, hundreds of fans are still drinking, socialising and, crucially, still spending. It is a social scene, a commercial scene; it is the difference between the silence of an empty football ground and the noise of a thriving stadium-based business. It is an example of the fabled “dwell time”.

This, in part, is why Tottenham Hotspur earn so much money on matchdays – £4.8 million ($5.9 million) on average – and part of why Tottenham’s revenue streams have turned into rivers. It is also why other clubs in an era of increased financial regulation and restrictions are looking at Spurs and considering relocating or redeveloping – Manchester United and Newcastle United among them.

At a time when the historic appeal of English football combines with the global popularity of the Premier League, when clubs are sports and non-sports businesses and commercialism chimes with heritage and architecture to form a must-see destination, the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium is the model. It is known for its scale, modernity and clear sightlines that have changed how many see football stadiums. It is, to use a phrase, groundbreaking.

But where to go, how to grow and what can be lost? These are complicated questions when stadia rise or fall and they inevitably lead to others regarding logistics and cost, downsides and benefits and whether a fanbase of yesterday and today wants – or is wanted – in a supposedly immaculate new tomorrow. Local vs global is a live tension.

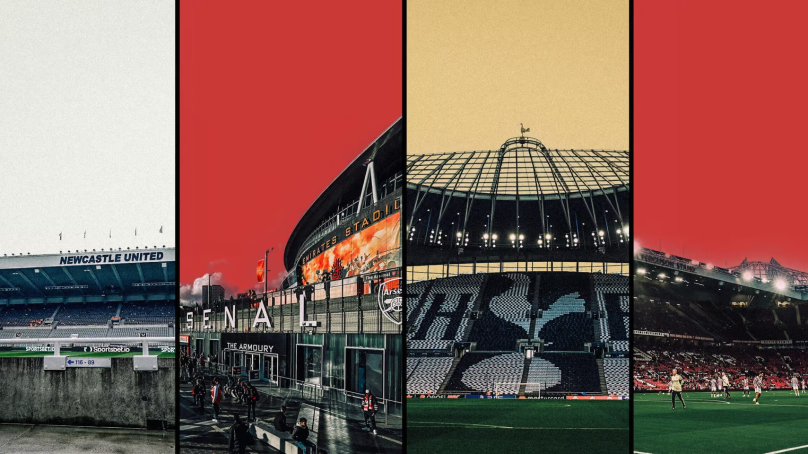

The Athletic has taken a tour of four Premier League clubs who have moved or who are thinking of moving – Arsenal, Tottenham, Manchester United and Newcastle United – to explore the advantages and disadvantages.

At Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium, a hawk is brought in twice a month to scare the pigeons and a pair of Thierry Henry’s socks are in a time capsule beneath the ground. At Tottenham, there is the longest bar in Europe – see above – huge NFL-specific spaces and you learn captain Son Heung-min sits in Harry Kane’s former middle seat in the semi-circle of the dressing room with James Maddison and Cristian Romero on either side.

At Old Trafford, Manchester United sell, proudly, the cheapest pint in the Premier League at £3.40. The old players’ tunnel behind where the managers stand is the last piece of the original construction from 1910, metre-thick walls that even Second World War bombs could not destroy. At St James’ Park, the vista looking north east from the top of the main Milburn Stand is magnificent and, on the walls downstairs, there is evidence Newcastle United have made a radical departure before – from 1892-94 they played in red and white.

Walking away down the hill from St James’, Adam, 24, a Newcastle fan who travelled up from Merseyside to do the tour, says: “I really, really love St James’ Park, but if progress means we have to expand in a new stadium because of revenue, then… but I hope not. Overall, there is a pragmatic approach from fans, I think. A new stadium would be exciting, but there’d be hesitancy as well.”

Were Newcastle to have a shiny structure rising on the banks of the River Tyne, as with Everton on the Mersey, would that not generate anticipation?

“Goodison Park has been crumbling for a while,” he replies, “and Everton have needed to move. At the same time, Goodison kept them up last season and there’s no guarantee you get that if you move to a new ground. There is the risk of losing your atmosphere. At West Ham’s new stadium, you feel that passionate fanbase gets lost, the same with the Emirates.”

Karen Morris, a Manchester United fan doing the Newcastle tour, says: “I started going in the 1980s with my Dad, we had season tickets in the K Stand. I think we should go now. We need a more up-to-date stadium. It’s outdated.”

Would a move further out of Manchester be acceptable?

“I want to stay on the same land, one hundred per cent.”

The geography of the Tottenham Hotspur stadium is one of its many aspects. Much is made of the contrast between a £1 billion stadium and the old council estates it brushes up alongside and Spurs’ former home, White Hart Lane, built 120 years ago, felt more of a fit in that respect. But Martin Cloake of the Tottenham Hotspur Supporters’ Trust is delighted the new stadium is where it is.

“It’s important to us that the stadium is in the same place,” Cloake says. “Remember, the club wanted us to move to east London. One of the places most visited in the new stadium is the old centre circle from White Hart Lane. That sense of ‘it’s Tottenham, our place’, is important.”

At Arsenal, they were so concerned about the move from a beloved institution, Highbury, that the club began a process of ‘Arsenalisation’ at the new stadium, which is constructed a goal kick away in terms of distance but an unknown distance away in terms of that intangible metric, soul.

In the Arsenal museum, a plaque states: “Much of the mystique and glamour of Arsenal’s international reputation came from the legendary Arsenal Stadium, Highbury. A monument to popular culture, it received the title ‘Stadium’ at a time when most clubs had ‘Grounds’.”

Arsenal moved from Highbury in 2006, seven years after the decision to leave was made. One of the main reasons was the club felt it had outgrown Highbury. In seasons 1998-99 and 1999-00, Arsenal staged their Champions League games at Wembley to accommodate both rising ticket demand to see Arsene Wenger’s attractive, winning team and to fulfil UEFA’s corporate criteria.

The latter was also relevant to Arsenal’s finances – selling 60,000 tickets, including thousands of expensive corporate seats, meant a far bigger payday than staying at Highbury, where the capacity for UEFA matches was just over 35,000. Demand far outstripped supply and the economic and ticketing logic of Arsenal moving was clear.

Yet Highbury was ‘home’. In the 17 seasons before Arsenal left, they won four league titles and finished second five times. Highbury’s role in this is unquantifiable, but it certainly was a vivid piece of The Arsenal.

In the 17 seasons since (not including 2023-24), Arsenal have not won a single title. They have finished second twice. A brutal reading of those league standings would say the move from Highbury has not been justified.

But the numbers able to watch Arsenal has soared and, economically, it has been transformative. Arsenal’s turnover in 2005-06, the club’s last financial year at Highbury, was £137 million. In 2006-07, the first season at ‘the Emirates’, it was £200 million and a season later £223 million. Six weeks ago, Arsenal released their figures for the year ending May 2023 with “football revenue for the year” at £464 million. Last July, Arsenal could afford to pay West Ham £100 million for Declan Rice.

As it approaches its 20th anniversary in 2026, Arsenal’s new stadium will be of as much intelligence to those at the top at Old Trafford and St James’ Park as Tottenham’s. There are function and design lessons, as well as the financials.

As Nigel Phillips from the Arsenal Supporters’ Trust (AST) explains: “Arsenal moved in 2006 but got planning permission in 1999 to a design from the mid-1990s. This makes the Emirates almost a 30-year-old design and is so dated when compared to what Spurs have built.

“Another issue with the Arsenal stadium move is that of the £450 million project costs, £260 million was borrowed on a long-term basis via project bonds, but the other £190 million came from Arsenal commercial revenues. Basically, it was spending money from future revenues and this meant that when those actual seasons rolled by, there was no commercial cash to spend as it had been spent on the stadium build.

“This is what messed with Wenger and the competitiveness of the club for a long period of time.”

Arsenal still qualified season after season for the Champions League – and secured that income – but in 2010-11, for example, just five years after moving, Wenger was bemoaning his spending power: “We can’t buy players for £50 million, that is a fact.”

As the squad’s competitiveness plateaued, so did fans’ feelings about the team in its new surroundings. And, as Phillips says, “Fans’ relationship with the new ground is totally tied up with on-field performances.”

It is something Cloake mentions regarding Spurs. A new stadium needs big seasons or big moments to cement ardour and Cloake refers to the stadium’s opening game against Crystal Palace, in April 2019, when Son scored the first goal at the new home. Defeating Man City 1-0 there a week later (Son again) in the Champions League was another euphoric occasion.

“We played Everton before the Champions League final and there was this massive party going on,” Cloake recalls. “People were just so happy. A lot more were getting to the stadium much earlier and meeting their mates there. They were spending their time and their money in the stadium.

“The sightlines are really good, you can see what’s going on, it feels like a proper football stadium. The scale of it is fantastic as well and we haven’t left Tottenham.

“But, fairly quickly, we went into the (Jose) Mourinho and (Antonio) Conte era, when the football was some of the worst we’d seen. A narrative developed that the stadium was just a money-making machine, the atmosphere was rubbish and not as good as the old ground.”

Mikel Arteta has been commenting for some time on the improved atmosphere at Arsenal, which again is related to the team doing better.

“I just had a person that I haven’t seen for a while,” Arteta said last season, “and it’s the first time he’s been at the stadium for two years. He says it’s the best he’s seen ever since he was at Highbury.”

Highbury was labelled a ‘library’, we should not forget, though the rhyme was a factor. The two north London grounds are major employers locally. Tottenham, who stage concerts, NFL games and have a go-kart track underneath the pitch, will host matches at Euro 2028. It all needs workers.

But Cloake also notes the recent rise in ticket prices. There was a backs-turned demonstration from some fans at the Luton game. Chairman Daniel Levy is earning £6.5 million per annum. Ticket prices and availability are already an issue for Newcastle United season-ticket holders. Only five years ago, 23,000 attended St James’ for a League Cup tie against Leicester City, but that was after years of being worn down by Mike Ashley’s arid regime.

- The Athletic report