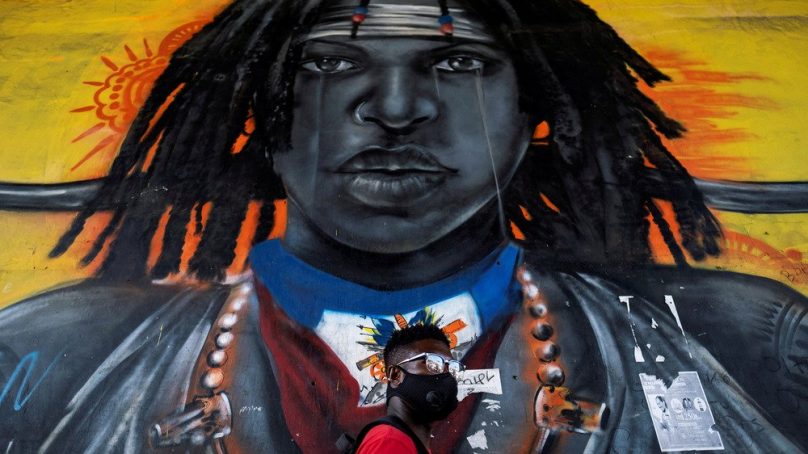

the outskirts of Haiti’s capital, gunfire crackles in the seaside shantytown of Cité Soleil. Children playing soccer freeze for a moment. Down the street, a teenager bandages the hand he injured during a gunfight with a rival gang.

The number of gangs in Port-au-Prince has grown from roughly three dozen in 2004 to more than 200 today – a worsening situation that could rob the Caribbean country of its future and prolong the need for long-term aid, according to civil society members, youth advocates, political groups, and humanitarian organisations.

Gangs have been part of the Haitian political landscape for decades – often deployed by leaders to rally support or quell opposition – but violence and kidnappings have reached unprecedented levels in recent months, making it harder for the government and aid groups to tackle the country’s overlapping humanitarian crises.

Persistent street protests have also thwarted business activities in the capital since 2018, largely involving restless youths angry about alleged government corruption and the lack of economic prospects.

Nearly half the population is under 24 – a young demographic with the biggest stake in Haiti’s future, and one that has a profound influence on everything from security issues and political stability to how the country copes with climate change risks.

Much of Haiti’s workforce is without formal work – employment prospects made gloomier since the pandemic. Frustrated by the absence of opportunity and a political malaise that began long before the July 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, young Haitians have increasingly turned to gangs as a way of earning cash or power.

In December, The New Humanitarian gained rare access to current and former gang members in the capital. Three Haitian journalists were key in reporting the story but their names are being withheld out of precaution for their safety.

Some former gang members spoke to reporters about lasting trauma from their deeds – another challenge for many entering adulthood. Others claim to have stepped in where the government has failed, filling a power vacuum and building an alternative future for the country.

“Gana Ti Zile”, whose nickname roughly translates to “small island”, joined a gang when he was 14. Now 35, he has become one of the leaders of G-Pèp, or People’s Gang, which controls part of Cité Soleil’s Brooklyn neighbourhood.

Unlike other gangs that have turned to kidnappings for ransom – even against Haiti’s poor, who can barely pay for food – Ti Zile said G-Pèp is helping the community, for example when the streets flood or to ease deliveries of international aid.

“It’s not normal to have young kids hold guns, but Haiti offers nothing.”

However, like so many other gangs in Haiti, G-Pèp still uses young children and teenagers for everything from running errands to fighting rivals. “There are young guys who fight with us… some die [and] some new ones come up,” Ti Zile said as he surveyed water marks from rising sea levels on some of the houses around Cité Soleil – climate crisis-driven risks that Haiti faces each year. “It’s not normal to have young kids hold guns, but Haiti offers nothing.”

Haiti’s many humanitarian problems are acute in Cité Soleil, a sprawling marginalised community of some 400,000 people where it’s international aid groups and local NGOs – not the government – providing the majority of basic services, such as water, electricity and education.

“The reality is that we residents of Cité Soleil are trapped,” one 20-year-old told The New Humanitarian, asking, out of security fears, that his name not be used. “I personally lost friends, killed just because they were passing particular neighbourhoods. Sometimes I can’t go to school; my mother can’t go to [work] because of the clashes. Every day, we risk death in one way or another. We should all leave here, but where to go?”

Gangs are not unique to Haiti. Other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are facing similar challenges with armed groups. But the political dysfunction in Haiti – made worse by decades of outside interference – has allowed them to flourish.

Social media has also helped propel the gangs. They often use live Facebook streams to grow their followers – some of whom said they were drawn to wanting the flashy garb gang members often wear. One rap song about Haiti’s gang culture asks what the next generation of Haitians will look like in 25 years. Another music video features a group of armed masked men rapping about “Izo 5 segonn” or “Izo 5 seconds” – the gang that rules Village de Dieu (Village of God), a lawless Port-au-Prince neighbourhood.

Gang violence has displaced some 19,000 people since the beginning of June 2021. At times, it has shut down the main road connecting the capital with the southern peninsula – a region still reeling from a 7.2-magnitude earthquake that killed some 2,200 people in August, as well as from Hurricane Matthew that killed hundreds and caused widespread devastation in 2016.

Haiti now has the world’s highest per capita number of kidnappings. Last year, there were 950, including a group of American and Canadian missionaries taken by the 400 Mawozo gang, which demanded a $17 million ransom. All the missionaries are now free.

Many people have also been killed. Two journalists were shot and killed by suspected gang members in January while covering the violence in Laboule 12, another neighbourhood in the capital.

According to Eric Calpas, a sociologist who has studied Haitian youth and gangs for more than two decades, the roughly 35 armed groups in existence in 2004 has now become more than 200, with some gangs having as many as 100 members, although precise data is difficult and dangerous to gather.

“The kidnapping system is where money can be found,” said Calpas, who worked in the UN’s peacekeeping mission between 2004 and 2008 as part of a unit that encouraged armed groups and gangs to disarm.

- The New Humanitarian report