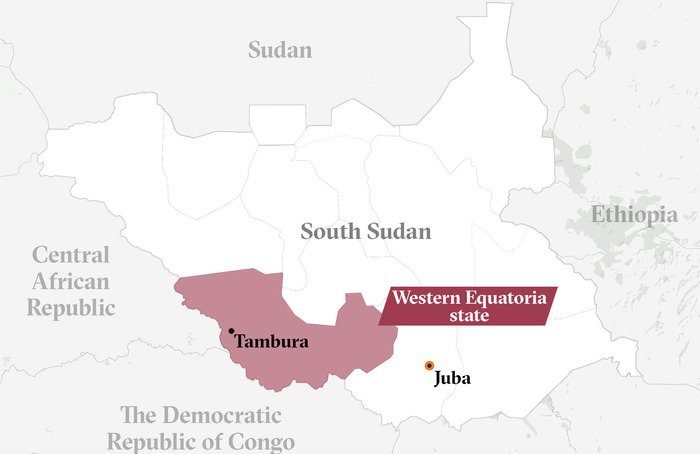

Politicians from South Sudan capital, Juba, have accused of supporting the formation of an Avungura-led militia in Western Equatoria reportedly backed by troops loyal to President Salva Kiir’s party, while a mostly Balanda militia was created with alleged support from opposition forces.

Both sides want to manage the state ahead of elections planned for 2023, according to analysts, and they have chosen Tambura as a battleground because political rivalries between the Azande and Balanda are most intense there.

“There is an opportunity to use control of local authority to seize an incumbency advantage,” said Mark Millar, an analyst for the Norwegian Refugee Council in South Sudan.

Though accounts of who triggered the violence vary, several interviewees cited community meetings in April and June 2020, when Azande leaders allegedly called for non-Azandes in Tambura to be killed or banished. Clashes intensified in mid-2021, further polarising communities, who said they had lived together with no major issues prior to the formation of the unity government.

Speaking from displacement camps outside churches or under trees next to military and UN bases, residents recounted brutal violence: unborn babies being ripped out of women’s wombs and bodies being dumped in wells.

Between August and September 2021, more than 2,000 people sought shelter in a local orphanage, said Bianca Bi Musungu, a nun who runs the home. She said the displaced left family members behind, including a child and elderly people unable to flee.

Musungu said an elderly man who was sheltering at the orphanage was killed in September while collecting ground nuts in his field. His body was found later, half-eaten by animals.

Luca, meanwhile, said her brother was also killed late last year while escaping the town during clashes. His body, like many others, was left on the road because it was too dangerous to retrieve. Luca said her house was burnt down during the violence, which resulted in her losing schooling documents for her children and medical paperwork she needs to access HIV medication. She described the war as “senseless”.

Since the October agreement involving community leaders in Tambura was signed, government and opposition troops have relocated outside of the county, while some local militias have turned over their weapons and promised to stop fighting.

“We are very sorry for what has happened,” said Akile Joseph, one of four Balanda-aligned fighters. The group admitted to killing men over 18, though denied receiving support from the opposition or politicians.

Still, local residents said they don’t feel safe and worry that militias are hiding in nearby forests, preparing to fight. “People are still in the bush. Maybe someone will come and kill me at night,” said Daniel Michael, a displaced person living beside a military post.

Wesley Welebe, an official who led an investigation into the fighting for the Joint Defence Board (JDB), a body charged with implementing parts of the peace deal, said he had received reports of Azande youth being recruited from displacement sites.

Welebe blamed much of the violence in Tambura on James Nando, an Azande former opposition commander who defected to Kiir’s party and joined the fighting last August. Nando claims to take orders from the National Security Service, according to a well-placed UN official who was present during talks with the militia leader.

Most Tambura residents who spoke to The New Humanitarian said they didn’t really understand who was stoking the violence, and that finding food and shelter were their main priorities.

Several residents in displacement camps said they had only received food from aid groups once since May 2021. Others said they tried to return home because their children were hungry, only to find their houses looted and crops destroyed.

Workers from relief organisations said they had struggled to assist the town’s inhabitants due to insecurity. During heavy fighting last year, activities were suspended and compounds were vandalised and looted.

The Tambura crisis has impacted other parts of South Sudan, said Matthew Hollingworth, country representative for the World Food Programme, which assisted almost five million people in the country last year.

Hollingworth said aid groups are now unable to source food from the fertile, agricultural county, and that diverting resources to those in need means spreading assistance “even thinner” elsewhere. On top of “localised violence”, he said aid groups are having to respond to a third year of mass flooding that has cumulatively impacted millions of people around the country.

“Too many people are, for the first time, desperate for all-year-round help, and a cash-strapped humanitarian community simply cannot respond adequately,” Hollingworth added.

Welebe of the JDB said sustainable peace in Western Equatoria needs a state cabinet reshuffle, a unified national army composed of government and opposition troops, and dialogue between local communities.

If none of this happens, the conflict could spread to other parts of the country where there have already been targeted killings of Azande and Balanda, including the capital, Juba, Welebe added.

Others said the peace agreement needs a more fundamental rethink.

“We have a problem of leadership, and we have a problem of political will,” said Abraham Awolich, a founding member of the People’s Coalition for Civil Action, a civil society group. “[The international community] should consider [the unity administration] a failing government which has lost legitimacy and should begin to engage with other voices.”

Tambura resident Lucia Anton – who lost her husband to the violence last year and was badly injured alongside her 11-year-old son in the same incident – said she was sceptical of any initiative seeking to stabilise her town.

“During the war, I wasn’t worried about being in Tambura,” Anton said from a displacement camp adjacent to a UN base. “[But] now there is no sign of lasting peace… Even if someone comes to discuss peace, we won’t believe them.”

- The New Humanitarian report