When Joe Biden won the US presidency earlier this month, it seemed like a huge opportunity to restore the country’s position as a leader in the fight against climate change.

But whether he’ll be able to deliver on his climate agenda – the most aggressive ever put forth by a leading US presidential candidate – remains to be seen, especially because he will face a powerful Republican opposition in Congress.

Still, climate-policy experts say that there is a lot the former senator and vice-president to Barack Obama can do, including exerting his authority over federal agencies to drive forward his agenda, and leveraging his experience working with both parties in the Senate to push legislation in Congress.

“This is really the first time that a US president is leading with climate,” says Vicki Arroyo, executive director of Georgetown University’s Climate Center in Washington DC. That’s exciting, she says, but suggests cautious optimism: global warming is still a partisan issue on Capitol Hill, dividing Republicans and Democrats, and “that is going to limit what Biden can accomplish”.

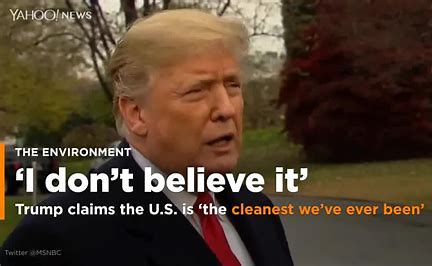

Biden’s election comes at a crucial juncture. President Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris climate agreement earlier this month, but other players on the world stage, from China to the European Union, are preparing to present a new round of commitments at the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow, UK, next year.

The president-elect has already set the stage for the United States to immediately re-join these negotiations. On November 23, Biden named John Kerry as his special envoy for climate change and gave him a seat on the White House National Security Council. Kerry served as secretary of state under Obama and was key to mediating the original Paris agreement.

Having the United States back on board will give an important boost to these negotiations, says Jean-Pascal van Ypersele, a climatologist at the Catholic University of Louvain in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, and former vice-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “The stars are much better aligned for a successful outcome in Glasgow than they would have been if Trump had been re-elected.”

Biden and other Democrats hoped their party would wrest control of the US Senate during the recent presidential election. Although Democrats will retain control over the House of Representatives by a narrow margin, Republicans performed better than expected in the Senate. The final seat count in that chamber is up in the air, and will depend on the results of a pair of January run-off elections in Georgia. No matter the result, Congress will be narrowly divided between the parties, making it challenging for Biden to pass significant climate legislation.

Biden’s first opportunity to advance his agenda through Congress could, as with Obama, come in the form of an economic stimulus bill. With the US economy reeling from the pandemic, many analysts expect this to be at the top of Biden’s agenda when he enters office. His team has made climate a central feature of its economic plan and could use a stimulus package to increase federal investments in low-carbon energy and green infrastructure.

But that is where the similarities to Obama’s approach might end. After the stimulus bill, Obama’s administration worked with congressional Democrats on legislation to drastically cut US greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 – but that bill failed to pass the Senate in 2010.

Instead, Biden will probably look for ways to advance less-sweeping climate measures. One possibility that could garner some industry support would be legislation that sets federal requirements for clean-electricity generation, says Jeffrey Holmstead, a lawyer at the Bracewell law firm in Washington DC who worked at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under president George W. Bush.

Utilities currently have to grapple with a cumbersome patchwork of different state requirements for how they use renewable energy to meet their customers’ electricity needs. Holmstead says that a federal standard could simplify things and level the playing field for all utilities.

But the single biggest opportunity for Biden to advance his climate goals through Congress could be bipartisan legislation that creates a carbon tax to reduce US greenhouse-gas emissions — an idea that has backing among many conservatives and business leaders who are concerned about the climate.

One proposal developed by the Climate Leadership Council, a non-profit organisation based in Washington DC, would start with a modest $40-per-tonne tax on carbon dioxide emissions that would increase over time, with the goal of cutting US emissions in half by 2035. The proceeds would be refunded back to taxpayers.

Getting such legislation through the Senate won’t be easy, but it’s not impossible, particularly if Democrats take control of the chamber by winning the two run-off elections in Georgia, says Bob Inglis, who heads the Energy and Enterprise Initiative, a thin-tank that advocates politically conservative environmental solutions at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

“This is a major opportunity,” says Inglis. “It’s really better to do this by legislation, and if we can make it bipartisan, then we can make it durable.”

Regardless of what happens in Congress, many scientists and environmentalists expect Biden will immediately use his executive authority to advance his climate agenda across the full suite of federal agencies.

It wasn’t until Obama’s second term as president in 2012 that he got serious about sidestepping Congress and using his authority to battle climate change.

Under Biden, the interior department, for instance, could hasten the processing of federal permits to build offshore wind farms and other renewable-energy projects. The Department of Energy could raise energy-efficiency standards for appliances.

And the treasury department could work with financial regulators to develop rules on how publicly traded companies report the financial risks of climate change – a move that could help investors to make wiser choices and encourage businesses to take the issue more seriously.

- Politico newspaper report