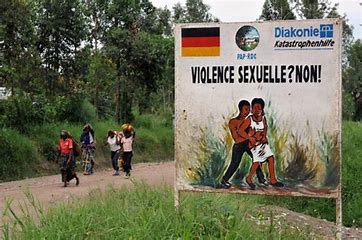

Even when sex abuse and rape cases are referred to local authorities in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where they occurred, it’s often an uphill battle when it comes to allegations involving UN personnel.

Take the alleged 2017 rape of a 16-year-old Congolese girl by a British man working for the UN peacekeeping mission. After her mother reported it to the UN mission, the allegations were substantiated, but UK authorities decided not to prosecute.

Paternity claims against UN personnel are also difficult to enforce, and enforcement is even harder when the suspected father has moved or returned to his home country.

Although a Haitian judge ordered a UN peacekeeper from Uruguay to make child support payments for a child he fathered, the order has been difficult to enforce. The UN often leaves national authorities to deal with such cases. In the case of UN peacekeepers, this often falls to the countries that contributed the troops.

“If the UN was serious about living up to its own stated standards of accountability and victim-focused response, it would create a system that takes direct responsibility for ensuring that victims have access to restitution and support.”

Several other paternity cases involving UN personnel are being litigated by the Haiti-based Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) and their partner organisation, Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH).

“If the UN was serious about living up to its own stated standards of accountability and victim-focused response, it would create a system that takes direct responsibility for ensuring that victims have access to restitution and support,” said Sasha Filippova, senior staff attorney with IJDH.

“Our cases in Haiti illustrate that in practice, it means there is none,” Filippova said, adding that in crisis-wracked countries like Haiti, survival needs often become the priority over accountability and restitution.

There also appears to be a stark difference in the time it takes to investigate some claims. Take the case of Rosie James, a 26-year-old doctor working for the UK’s National Health Service, who said in October that she was sexually assaulted by a WHO staffer while attending a WHO-sponsored conference in Berlin.

WHO suspended the staffer within weeks of the complaint and launched an investigation. The UN health agency has boosted its investigative capacity since the Ebola sex abuse scandal. Yet, more than two years since the scandal broke, investigations into the 2018-2020 abuse claims in DR Congo are still ongoing.

“The UN has essentially created a two-tier system for survivors of sexual abuse and exploitation at their hands,” said Priyanka Chirimar, an international human rights lawyer who worked for the UN for 10 years, and now litigates before UN employment tribunals for victims and survivors.

The UN embraces a “survivor-centred” approach when it comes to victims of sexual abuse and exploitation, but women and girls lured into sex-for-work schemes by aid workers during the 10th Ebola outbreak say the reality is much different.

The approach is intended to “put the rights of each survivor at the forefront of all actions and ensure that each survivor is treated with dignity and respect,” the UN states. It is also designed to put survivors “at the centre of the process”.

Part of that process involves asking victims if they want to pursue criminal cases or paternity claims. During The New Humanitarian’s reporting, dozens of victims agreed to share details with investigators to discuss potential legal avenues.

“They came to get information from us victims, then left us with nothing,” one 28-year-old woman said in September, recalling her interview with investigators from the independent commission.

Outside of victims’ legal options, one of the most under-resourced and little-discussed areas in the prevention of sexual abuse and exploitation is redress and compensation, according to the Core Humanitarian Standard Alliance (CHS Alliance), a network of non-governmental organisations working in humanitarian aid that focuses on improving the aid sector’s accountability to people in crisis.

Under international law, victims of human rights violations have a right to adequate, prompt and effective access to remedies and reparation. Reparation can take many forms, including medical and psychological rehabilitation, restitution, public apologies, financial compensation or other measures that could include bringing perpetrators to justice.

Although the UN’s rights body has advocated for reparations in the cases of sexual violence and human rights violations, the UN says its own rules prohibit payment of reparations. Reem Alsalem, the UN’s special rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences, was one of several critics of how WHO handled the sex abuse scandal.

When contacted, she said any victims’ assistance needed to be relevant and with regular monitoring.

“What is also very important is whatever you do for victims is transformative, that it doesn’t just bring them back to their situation before the violation, that it actually leads to a significant improvement in getting them out of structural inequality and violence that they’ve been suffering from,” she told The New Humanitarian.

The Global Survivors Fund (GSF) is one such group providing a template for how governments (and potentially organisations) can address the multifaceted harms and stigmatisation suffered by victims of sexual violence through reparations.

GSF tries to galvanise states to take up their responsibility. GSF projects in Guinea and DR Congo have already shown that where such measures are “co-created” with survivors they have had real impact, said Esther Dingemans, executive director of the Geneva-based group.

“Our approach is to just start showing how these models can work. But you need to just start talking about reparation rather than shying away from it. The how, who, and what will become clearer in the process of co-creation with the survivors,” Dingemans said.

Danaé van der Straten Ponthoz, also with GSF, added: “Justice and reparation are completely interlinked.”

- The New Humanitarian report / By Paisley Dodds and freelance journalist Jonas Gerding