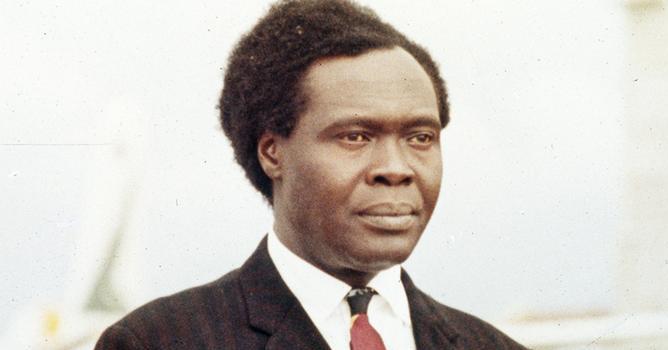

The former Presidents of Uganda, Apollo Milton Obote and Idi Amin, and their perennial successor, Tibuhaburwa Museveni, imposed themselves into the citizens of Uganda.

Apollo Milton Obote became leader of Uganda through a General Election in April 1962, in which he never presented himself to the electorate to be voted or not voted into power. He was forced out of power both in 1971 and 1985 without ever giving the citizens of Uganda the right to either vote or not vote for him. It seems he loved elective politics so long as he was not a subject to the vote.

In 1962 and 1980, he rose to the top job in the country simply by his party, the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) edging ahead of the Democratic Party candidates (Ben Kiwanuka in 1962 and Paul Ssemogerere in 1962), although in 1962 he needed an alliance with Kabaka Yekka (King Only) Party to capture the Premiership of Uganda from Ben Kiwanuka’s Democratic Party.

Obote did not really get an opportunity to transit to Oboteism. He spent virtually his two reigns (1962-1971 and 1980-85) struggling for political legitimacy in a much-divided country. Between 1962 and 1971 it was Buganda hegemony that was testing his legitimacy to lead Uganda with Buganda as part of it. If Idi Amin had not intervened to depose Obote, most likely his evolving Common Man’s Charter would have been the embodiment of Oboteism: mixing socialism with democracy and social development of Uganda from bottom up. The Common Man’s Charter was thus an ideological document, which Obote submitted to his political party, forming a part of the country’s move to the Left.

Obote asserted, in the document, several key principles of his vision for Uganda, apparently including a commitment to democracy. The document was signed into law on October 24, 1969 under the subtitle “First Steps for Uganda to Move to the Left”.

Simultaneously, however, President Obote was increasingly relying on the army, commanded by Idi Amin to rule. While he preserved the integrity of Parliament and the Judiciary, the former was being more attuned to underpinning his Vision for Uganda, although his social programme served the interests of the citizens in terms of quality education, quality health and quality agriculture. There is no evidence, however, to suggest that when he recaptured the instruments of power following a much-disputed general election, he tried to revive the Common Man’s Charter.

Resistance to his second reign almost immediately meant that he had no time to reintroduce the Common Man’s Charter nor revitalize his social programme. There were many human rights violations, but most of these could have been by his armed opponents trying to convince the people that Obote’s regime had no capacity to assure their security.

When Idi Amin overthrew Obote on January 24, 1971. He made it clear he would not entertain orthodox politics based on parliamentary democracy when he said, “I am a professional soldier, not a politician. That marked the end of parliament as an arm of government. He, however, left the judiciary to continue functioning, although within limits set by himself. When Chief Justice Ben Kiwanuka tried to work professionally to preserve the judicially as an effective arm of government in a militarised environment, he was eliminated and his body was never recovered.

The epitome of evolving Aminism was that he was the beginning and end of law, and for the most time he ruled by decrees. Decrees are official orders that have force of law. So it was Amin’s orders that the judiciary had to preoccupy itself with to administer justice. What routinely emerged from the courts was injustice. Aspects of Aminism were:

- An executive over-infested with soldiers as ministers;

- Supersonically rising extrajudicial killings; total absence of political activities;

- Militarism as both a faith and practice of governance;

- Rising nepotism, kinship and ethnicity at the centre of leadership and governance;

- Suppression, repression and oppression;

- Institutionalised injustice;

- Decay and collapse of institutions;

- Human rights violations;

- Presidentialism;

- Kondoism (armed crime) and other crimes;

- Decay and collapse of social services (i.e. education, health, agriculture);

- Collapse of production and rising dependence of foreign handouts;

- Mafuta mingi in business and trade;

- Collapse of cash crop economy;

- Xenophobia towards Indians.

In his book Uganda’s Transition from Amin to Aminism: Exploring Yoweri Museveni’s Anglo-American Backed Dictatorship and the Fundamental Change that Never Was, published by Amazon in 2011, Kizito Michael George wrote this:

When Museveni captured power in 1986 and promised Ugandans a fundamental change, many Ugandans were optimistic that the tyrannical days of dictators like Amin were over. After decades in power, according to Kizito Michael George, Uganda simply made a transition from Amin to Aminism. In my view Aminism is indeed seen in what I have listed above. If we take Musevenism as the other side of Aminism then the list contains all the elements of Aminism. But we would have to remove Xenophobia towards Indians and Mafutamingi in business. We would have to replace them with over-exaggerated affinity for Indians, Chinese and refugees. We would then have to add pseudo-military democracy (or politico-military democracy), election rigging, corruption scandals, primitive capital accumulation, and consummation of the Executive, Legislature and Judiciary by the personal power of President Tibuhaburwa Museveni. According to Kizito Michael George (2011), Museveni (read Musevenism) was created by the Anglo-American Neoliberal Alliance. This could explain why President Museveni has stuck to the falsehood of ‘Liberalised Economy’ and resisted intervening to or things right, even when it is clearly hurting the people, by insisting that the market will solve the essentially social problems such as unemployment and hunger. By this reasoning, the President sees the benefits of the liberal economy trickling down to the bottom of society and solving the social problems there. However, it is not easy to see how this will solve the rampaging land grabbers of largely one ethnicity, which is displacing and dispossessing indigenous Ugandans.

Just like the case if Castroism (Albert Weusbord, 1962) in Cuba, Musevenism is proving to be a deadly danger to current and future Uganda. Fidel Castro attached himself from the top to the people who never sent him to the bushes of Latin America to fight for power, and essentially looked at them from the mountain peak of his intellectual contempt. (Albert Weisbord, 1962). To entrench himself in power, Castro ensured that the workers and the toilers were not entirely free to vote their choices and to participate actively in all government activities.

This is what President Tibuhaburwa Museveni has adopted in Uganda. He even boasts every time there is an election that, “Nothing cannot be unless his party (read Museveni) wills. Museveni type revolutionaries are very much like those that obtained in Cuba under Castroism:

- Upper-class leadership with purposely disorganised bottom

- Reliance on a well-capitalised tiny conspiratorial military (junta) initiative launched from the bushes of Luwero.

- Caudillism (i.e, a system of sociopolitical domination based on the rule of a strongman who can decide and undecided anything with no regard to institutionalism or constitutionalism.

- Personalised political power

- Vague political statements of being for the people, yet maintaining “I don’t work for anybody but myself, family and grandchildren”

- Forced industrialisation against native investments and driven for and with foreign investors..

- Separation of the sciences (Humanities, Social Science, Natural Science) in favour of Natural Science and pertinent professions.

- Over emphasis on military security at the expense of social security

- Every new military conspiracies in Uganda and East Africa

- Hiding the social programme behind liberalised economy and security

- The President Projecting himself as the only true and indispensable leader

- Clannism based on kinship and ethnicity

- Numerous military promotions at the expense of others in other spheres of the economy

- Creating soldiers as the new landlords of Uganda

- Large public works such as hydropower dams

- Co-option of politicians from Opposition other than completely opening up political space.

- Impoverishment through economic schema such as Myooga, Operation Wealth Creation and Parish Development Model

- Proliferating slavery within Uganda and beyond, mainly in the Middle East, with accompanying illicit trade in human organs

It is clear the revolution President Tibuhaburwa Museveni repeatedly talks about every other time and commemorates every year since 1986 at great expense to the taxpayer does not include rethinking and liberating Ugandans from this spectrum of vices. There was us no indication the vision the president says he has for Uganda includes liberating Ugandans from the Anglo-American Neoliberal Alliance.

With the recent revelations that Uganda is one huge landmass of minerals of all types may mean that the country will go further in the grip of the Anglo-American Neoliberal Alliance, perhaps against competition from Russia and China.

However, the enormous indebtedness of the NRM government to China may greatly distort future relations between Uganda and the outside world, particularly UK and USA and perhaps within East Africa. Uganda government gets most of its military gear from Russia and China, although the Anglo-American Neoliberal Alliance supplies son military hardware and money too.

For God and My Country