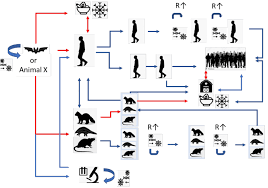

After the breakout of coronavirus in Wuhan city, Chinese researchers collected nearly 1,000 samples from the Huanan market in early 2020, swabbing doors, rubbish bins, toilets, stalls that sold vegetables and animals, stray cats and mice. The majority of the samples that tested positive were from stalls that sold seafood, livestock and poultry.

The researchers also took samples from 188 animals from 18 species at the market, all of which tested negative. But these animals do not represent everything sold in the market, notes WHO team member Peter Daszak, president of the non-profit research organisation Ecohealth Alliance in New York City. “A thousand samples is a great start, but there’s more to do,” he says.

Daszak points out that researchers traced farmed animals at the market back to three provinces in China where pangolins and bats carrying coronaviruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 had been found. Although the pangolin and bat viruses proved too distant to be the direct progenitors of SARS-CoV-2, Daszak says that the animals might provide a clue that outbreaks among animals started in those places.

The WHO report also concludes that it’s highly unlikely that the coronavirus escaped from a lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Most scientists say that evidence overwhelmingly favours SARS-CoV-2 having spilled over from animals into humans, but a few have backed the idea that the virus was intentionally or accidentally leaked from a lab.

When the report authors visited the institute, its scientists told them that no one in the lab had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, ruling out the notion that someone there had been infected in an experiment, and had spread it to others.

The Wuhan researchers also said that they hadn’t kept any live virus strains similar to SARS-CoV-2. And in their discussions with the investigative team, they pointed out a Nature Medicine paper1 showing that similar viruses exist in animals in China, rather than in their lab.

They further explained that everyone in the lab has safety training and psychological evaluations, and that their physical and mental health are continuously monitored.

“We were allowed to ask whatever questions we wanted, and we got answers,” says Daszak, who collaborates with researchers at the Wuhan institute. “The only evidence that people have for a lab leak is that there is a lab in Wuhan,” he adds.

Nevertheless, the findings are likely to be contested by some. A small group of scientists have sent letters to the media saying that they wouldn’t trust the outcome of the investigation because it was closely overseen by China’s government.

But others say that the WHO team’s conclusions seem solid. “I’m sure people will say that the Chinese researchers are lying, but it strikes me as honest,” argues Holmes. Matthew Kavanagh, a global-health researcher at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, says that he’s heard no evidence pointing to a lab escape. “But the sceptics are going to want a deeper investigation than the Chinese government allowed,” he says.

He adds that it’s challenging for the WHO to carry out such studies. “The WHO is in a completely impossible position because they are being criticized for not holding China accountable, but they are given almost no tools to compel any country to cooperate,” he says.

China holds information closely, and “in that context, the WHO’s team has gotten a good look at a lot of data – but it can only get so far”.

Some studies have suggested that Covid-19 was spreading among people before December 2019. To explore that possibility, the report authors looked at analyses of SARS-CoV-2 sequences collected from people in January 2020, and estimated that they evolved from a common ancestor between mid-November and early December of 2019. That estimate roughly corroborates the findings of a report published in Science this month.

The researchers also looked at death certificates in China and found a steep increase in the number of weekly deaths in the week beginning January 20, 2020. They found that the death rate peaked first in Wuhan, and then, two weeks later, in the wider province of Hubei, suggesting that the outbreak began in Wuhan.

The report also publishes data on people seeking care for respiratory infections, which similarly suggests that Covid-19 didn’t begin taking off until January.

As for reports of SARS-CoV-2 circulating in Italy and Brazil in October and November 2019, the report calls these studies inconclusive because they were based on partial sequences of SARS-CoV-2, and therefore could be a case of mistaken viral identity.

But inconclusive doesn’t mean impossible. And Tedros indicates that there will be more work to come. “This report is a very important beginning, but it is not the end.”

- A Nature report