Joe Weisberg – the geopolitically entangled, heavily therapised creator of The Americans and The Patient – is the trickiest character he’s written (so far).

“Did you learn things in CIA training about withstanding interrogation that are going to make it harder for me to interview you?” I asked Joe Weisberg, creator of the TV espionage drama The Americans and onetime CIA agent. He looked momentarily startled, as though he’d expected this to be easier.

Good, I had him where I wanted him: off-balance. I saw him taking my measure. Then he laughed affably, but I mistrusted the affability, since I knew from his own books that affability is among the qualities the CIA recruits for: people who can get other people to trust them or at least want to have lunch with them.

I suppose I had certain fantasies about interviewing an ex-spook (was he equally profiling me? more skillfully?), no doubt the result of having read too many John le Carré novels. As it happens, reading le Carré had a lot to do with propelling Weisberg himself to spy-craft.

Sure, he knew it was a fantasy world being depicted, but it was still a world he felt he belonged in. There was also his consuming obsession with bringing down the Soviet Union, which unfortunately for his career aspirations was soon to collapse on its own.

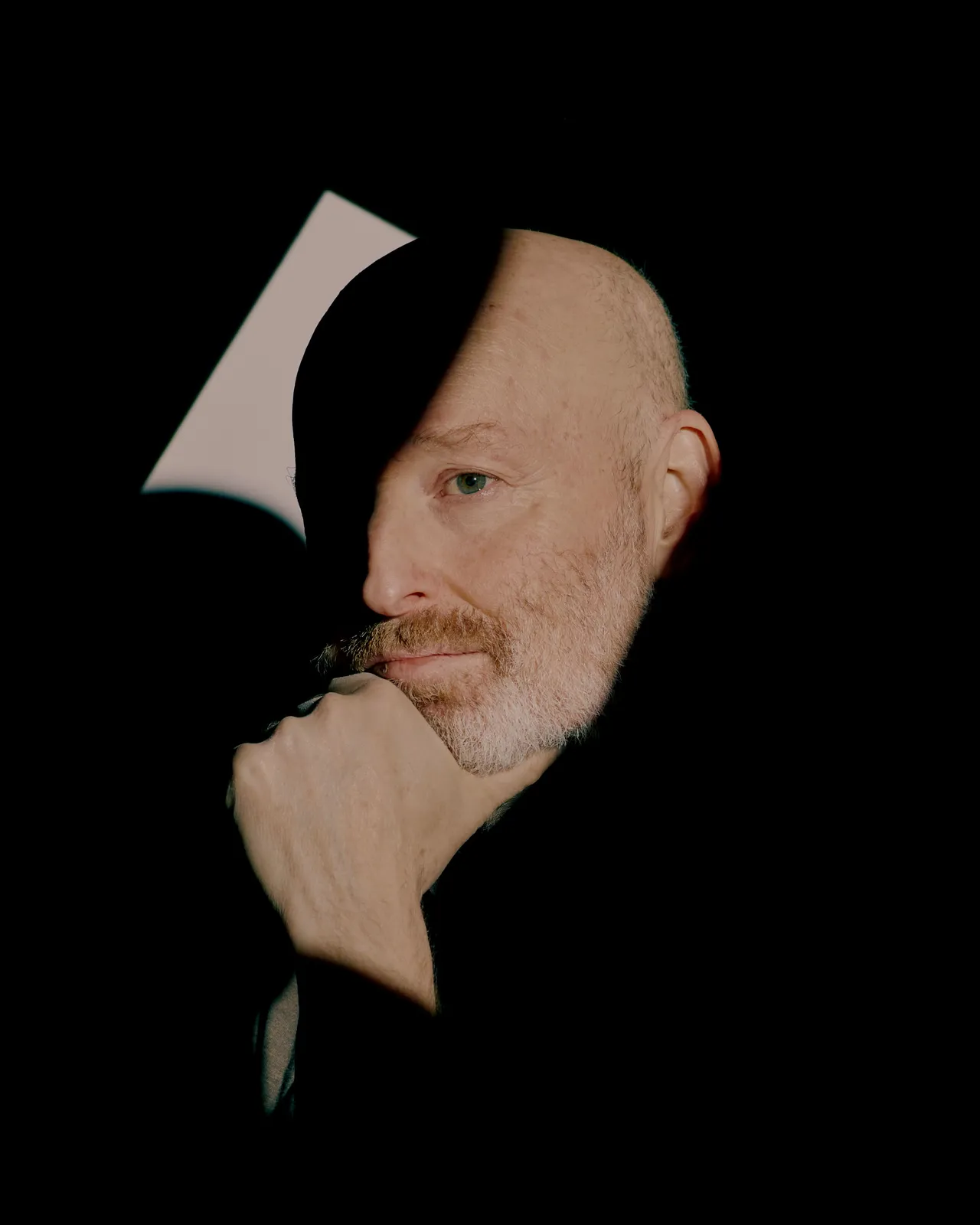

Weisberg, who is 57 and on the short side, has a sharp, possibly even hawkish visage along with an invitingly squishy-liberal midsection, which in combination externalise the essential duality in his being, one that’s both shaped his life story to date and yielded one of the most complex married couples in television history, the Russian sleeper agents Elizabeth and Philip Jennings. The Americans aired on FX from 2013 to 2018, but everyone I know seems to be compulsively binge-streaming it lately – maybe the fear that your neighbours are plotting to bring down democracy somehow resonates again with the mental state of the country?

Loosely based on the FBI’s 2010 arrest of a network of Soviet spies living under assumed identities in the US, the series springs at least as much from the depths of Weisberg’s psyche. Elizabeth, a cold warrior to her core, is, Weisberg says semi-jokingly, him pre-therapy; the détente-curious Philip is him after.

Therapy also figures significantly in his more recent limited-run series, The Patient, created with his writing partner Joel Fields (they were showrunners together on both series) and starring Steve Carell as a shrink horribly unlucky in his clientele. Something haunts me about both these shows, and not just because they feel like case studies in American paranoia.

At a time when most scripted television specialises in moral preening – trafficking in sentimentality, pandering to liberal do-gooderism, leaving us feeling better about ourselves and the world – Weisberg’s shows put you through a merciless psychological and spiritual wringer. They’re willing to leave you floundering.

So what about those interrogation-evading techniques? I pressed Weisberg. We were chatting in his downtown apartment, the top two floors of a century-old building – gracious entryway, high-ceilinged rooms, also a rental and steep third-floor walk-up with an inoperable buzzer. (“Joe doesn’t have fancy taste, he’s not acquisitive, he’s not super-interested in money,” says his brother, Jacob.)

- A Wired report

Decorative touches include his late mother’s porcelain eggcup collection, a row of family photos (some “off the record” – Weisberg is divorced and has a teenage daughter), the residues of successive hobbies: photography, painting, cooking and a wall of serious-looking books. The vestibule is devoted to an extensive high-tech backpack collection: his only consumerist passion is an unequivocally nerdy one.

What I really wanted to know was what he’d learned about getting inside people’s heads – knowing what your adversaries are thinking, using their desires against them. It’s what’s so seductive about le Carré: his operatives aren’t just spies; they’re master psychological strategists. As are Philip and Elizabeth Jennings, always knowing the precise right play: who’s dissembling, where’s the weak spot.

Does CIA training give you a leg up at that kind of thing in later life? Does it make you better at grasping dark human complexities, thus at writing layered and contradictory characters?

It turned out I had it backward. The secret to writing success goes deeper than on-the-job training. It requires a willingness to pursue your monomanias wherever they lead. It requires, Weisberg eventually divulged, finding a good enemy. “When I was younger, having an enemy gave me a purpose, because the purpose is to fight the enemy,” he told me. “It’s hard to describe how alluring that was. If you have an enemy, everything makes sense.” There it was: scratch the affability, uncover a gladiator. If I wanted to understand Weisberg, and maybe human creativity generally, I realised I’d have to understand the symbolic function of The Enemy.

In the Cold War years, a good enemy wasn’t hard to locate. Although only 14 when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and not especially political, Weisberg was outraged over the brutality and injustice of the war and saw the mujahideen (some factions of which would become the Taliban) as heroes. Maybe it had to do with his father reading aloud nightly from the Russian classics to Joe and Jacob – Tolstoy, Turgenev, Gogol, Dostoevsky – from when he was five on, meaning that the romantic world of imperial Russia was lodged deep in his imagination.

Maybe it was the Sunday school inculcations about the oppression of Soviet Jewry. Either way, his fantasy life – he’d been writing novels from the time he was 12 – became devoted to saving innocents from repression, and what he knew more than anything was that America needed to liberate the freedom-loving people of Afghanistan.

In college, ever more convinced that the USSR imperilled world peace and ever more drawn to the thralls of absolutism, he became – despite having grown up in an ardently liberal household – a Reagan devotee. Switching his attentions from literature to become a history major focused on Russia, he wrote a senior thesis asking if the Soviet population supported their government’s leadership. (He now wonders if his entire career since has been devoted to rehashing that paper.)

At Yale, conservatives were then in short supply, at least among the student population, and being vocally pro-Reagan had its social disadvantages. Even if he didn’t identify as a social conservative, rumours circulated among friends back home that he’d become a racist. In an office-hours meeting with a writing professor he’d thought he was on friendly terms with, she suddenly blurted out, “You can be such an asshole!” He was baffled, but maybe he also was a bit of an asshole.

“You do nasty things,” he’d later write about his pre-therapy self. “You behave in strange ways when your feelings are obscured from you. You don’t have the tools to do anything else.”

The Soviet obsession continued post-graduation: he studied Russian, went to Leningrad to study more, got a job in Chicago helping Soviet émigrés find jobs. Bored, one day he called the CIA to request a job application. After 18 months of tests and interviews, he started training at the agency’s semi-secret compound in Langley, learning to fire weapons and detect surveillance.

That was the exciting part; less thrilling was a six-week classroom slog memorising the bureaucratic ins and outs of the CIA.

He met guys, rough guys, who while operating in Afghanistan had grown beards and donned traditional robes, riding around on horseback with the mujahideen. although afraid of horses, and although the Soviets had by then left Afghanistan, this was the career Weisberg wanted.

As far as interrogation-withstanding, he recounted the day when trainees were kidnapped from their barracks, blindfolded, put in a truck, then taken into a room and questioned. If you wouldn’t talk, they made you stand in awkward positions. He doesn’t think he really learned much, other than a phrase one of the trainers wore on his hat: “Admit nothing, deny everything, make counter accusations.” “I may do that,” he said, apropos our interview. The other takeaway was to always have a cover story prepared.

- A Wired report