In 2010, Theresa Chaklos was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia – the first in a series of ailments that she has had to deal with since. She’d always been an independent person, living alone and supporting herself as a family-law facilitator in the Washington DC court system. But after illness hit, her independence turned into loneliness.

Loneliness, in turn, exacerbated Chaklos’s physical condition. “I dropped 15 pounds in less than a week because I wasn’t eating,” she says. “I was so miserable; I just would not get up.” Fortunately a co-worker convinced her to ask her friends to help out, and her mood began to lift. “It’s a great feeling” to know that other people are willing to show up, she says.

Many people can’t break out of a bout of loneliness so easily. And when acute loneliness becomes chronic, the health effects can be far-reaching. Chronic loneliness can be as detrimental as obesity, physical inactivity and smoking according to a report by Vivek Murthy, the US surgeon general. Depression, dementia, cardiovascular disease and even early death have all been linked to the condition.

Worldwide, around one-quarter of adults feel very or fairly lonely, according to a 2023 poll conducted by the social-media firm Meta, the polling company Gallup and a group of academic advisers. That same year, the World Health Organization launched a campaign to address loneliness, which it called a “pressing health threat”.

But why does feeling alone lead to poor health? Over the past few years, scientists have begun to reveal the neural mechanisms that cause the human body to unravel when social needs go unmet. The field “seems to be expanding quite significantly”, says cognitive neuroscientist Nathan Spreng at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. And although the picture is far from complete, early results suggest that loneliness might alter many aspects of the brain, from its volume to the connections between neurons.

Loneliness is a slippery concept. It’s not the same as social isolation, which occurs when someone has few meaningful social relationships, although “they’re two sides of the same coin”, says old-age psychiatrist Andrew Sommerlad at University College London. Rather, loneliness is a person’s subjective experience of being unsatisfied with their social relationships.

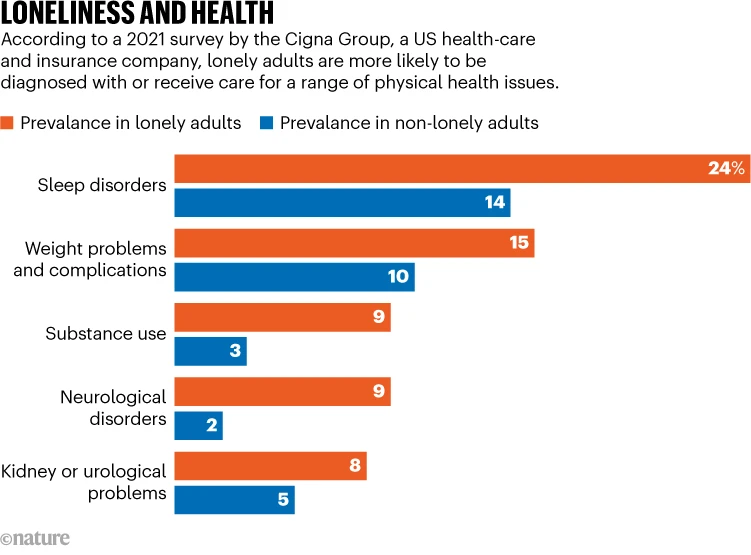

The list of health conditions linked to loneliness is long and sobering. Some of these make intuitive sense – people who feel lonely are often depressed, for example, sometimes to the point of being at risk of suicide. Other links are more surprising. Lonely people are at greater risk of high blood pressure and immune-system dysfunction compared with those who do not feel lonely, for example. There’s also a startling connection between loneliness and dementia, with one study reporting that people who feel lonely are 1.64 times more likely to develop this type of neurodegeneration than are those who do not3.

A number of physiological effects, including the ability to sleep, increased stress-hormone levels and increased susceptibility to infections, could link loneliness with health problems. But the way in which these factors interact with one another makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of loneliness from the causes, cautions cognitive neuroscientist Livia Tomova at Cardiff University, UK. Do people’s brains start functioning differently when they become lonely, or do some people have differences in their brains that make them prone to loneliness? “We don’t really know which one is true,” she says.

Whatever the cause, loneliness seems to have the biggest effect on people who are in disadvantaged groups. In the United States, Black and Hispanic adults, as well as people who earn less than $50,000 per year, have higher rates of loneliness than do other demographic groups by at least 10 percentage points, according to a 2021 survey by the Cigna Group, a US health-care and insurance company. That’s not surprising because “loneliness, by definition, is an emotional distress that wants us to adapt our social situations”, says geriatrician and palliative-care physician Ashwin Kotwal at the University of California, San Francisco. Without financial resources, adapting is harder.

The Covid-19 pandemic might have exacerbated loneliness by forcing people to isolate for months or years, although “that data is still emerging”, Kotwal says. Older adults have long been thought of as the demographic most heavily affected by loneliness, and indeed it is a major problem faced by many of the older people that Kotwal works with. But the Cigna Group’s data suggest that loneliness is actually highest in young adults – 79 per cent of those between the ages of 18 and 24 reported feeling lonely, compared with 41 per cent of people aged 66 and older.

A growing amount of research is exploring what happens in the brain when people feel lonely. Lonely people tend to view the world differently from those who aren’t, says cognitive neuroscientist Laetitia Mwilambwe-Tshilobo at Princeton University in New Jersey. In a 2023 study, researchers asked participants to watch videos of people in a variety of situations – for example, playing sports or on a date – while inside a magnetic resonance imaging scanner.

People who did not report being lonely all had similar neural responses to each other, whereas the responses in people who felt lonely were all different – from the other group and from each other. The authors hypothesized that lonely people pay attention to different aspects of situations from non-lonely people, which causes those who feel lonely to perceive themselves as being different from their peers.

This would mean that loneliness can feed back on itself, becoming worse over time. “It’s almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Mwilambwe-Tshilobo says. “If you think that you’re lonely, you’re perceiving or interpreting your social world more negatively. And that makes you move further and further away.” Some studies have shown that this effect can spread through social networks, giving loneliness a contagious quality.

Historically, staying close to others was probably a good survival strategy for humans. That’s why scientists think that temporary loneliness evolved — to motivate people to seek company, just as hunger and thirst evolved to motivate people to seek food and water.

In fact, the similarities between hunger and loneliness go right down to the physiological level. In a 2020 study, researchers deprived people of either food or social connections for 10 hours. They then used brain imaging to identify areas that were activated by images of either food – such as a heaping plate of pasta – or social interactions, such as friends laughing together. Some of the activated regions were unique to images either of food or of people socialising, but a region in the midbrain known as the substantia nigra lit up when hungry people saw pictures of food and when people who felt lonely saw pictures of social interactions. That’s “a key region for motivation – it’s known to be active whenever we want something”, says Tomova, who is an author on the study.

- A Nature report