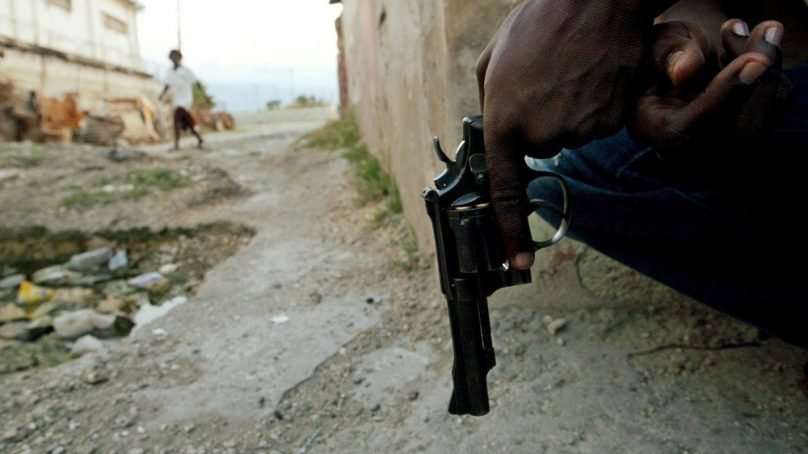

Haiti’s surge in gang violence and kidnappings is forcing aid organisations to rethink shipment routes, staff risks, and security costs – and to consider the ethical and safety implications of trusting leaders of armed gangs who say they can help.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Haiti, and is notably prevalent in Latin America. From Brazil to Colombia to Peru, humanitarian organisations are in a difficult bind: Negotiate with armed groups and gangs, or accept that staff may be put in more danger or that aid won’t reach some of the people who need it most.

In Haiti, rampant gang violence has meant delays in getting help to an estimated 4.9 million people in need of assistance, some of whom were impacted by the 7.2-magnitude earthquake on 14 August that killed more than 2,200 people in the country’s southern peninsula.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) estimates that more than half of the Haitians who need humanitarian assistance – 2.5 million of the country’s 11.4 million people – live under the control of armed groups.

In June, armed men shot and killed her mother and then burnt down her house during an eruption of violence in Martissant – a gang-riddled neighbourhood in the south of the capital, Port-au-Prince. Dupain sought shelter in Champs de Mars – a sprawling park near the ruins of the National Palace, destroyed in the catastrophic January 2010 earthquake that killed between 100,000 and 300,000 people.

Summer flooding soon transformed streets into rivers, and the park became a flashpoint for frequent gunfights between gangs. Dupain was forced to join 1,500 others living in a large gymnasium in Carrefour, in the city’s western outskirts. Roughly 19,000 people have been displaced by gang violence in the capital since June.

“There’s nothing left for me here,” Dupain, 32, told The New Humanitarian in November, adding that she hoped to migrate to the neighbouring Dominican Republic to be with her 15-year-old daughter. Together, Haiti and the Dominican Republic comprise Hispaniola, the second largest Caribbean Island after Cuba.

Disasters, political upheavals, and stark economic realities have driven many Haitians to seek opportunities abroad over the past decade, but the worsening gang violence has seen a recent surge in outward migration.

The number of gangs in the capital has skyrocketed since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July, according to Eric Calpas, a sociologist who has studied youth and armed groups for decades. In some neighbourhoods, it’s unclear which gang is in control, or if an area will suddenly be engulfed in gunfire between rival gangs.

For aid groups trying to deliver vital assistance, the situation is hugely problematic. Gangs control the area around the main port where fuel shipments arrive. They are also present in the industrial business zone where food is often stored, as well as along roads heading out of the capital towards the disaster-battered southern peninsula.

Some aid groups had been using a different route south through Laboule, but the area has recently become a battleground for rival gangs: Two journalists were recently killed there.

“Alternative routes [to the southern peninsula] don’t exist,” Christian Cricboom, country director for the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, said.

The unrest has forced some aid organisations and NGOs to curtail operations or stop them entirely. Médecins Sans Frontières, for example, shut down its hospital in Martissant in August due to the spiralling violence. The hospital, which is still closed, had been providing free treatment to more than 300,000 people.

Midwives for Haiti, meanwhile, had to limit clinics for pregnant women due to roadblocks and fuel shortages linked to the gang violence, according to country director Jean-Mariot Cléophat.

While others are scaling back, some aid organisations have stepped up their efforts exactly because of the violence and rising needs. The ICRC shuttered its operations in Haiti as the situation improved roughly four years ago, only to re-open an office after the August earthquake.

It has since been helping to improve access to healthcare services amid the uptick in violence and worsening fuel shortages.

“Violence has escalated – not only the level of violence, but the type of violence,” ICRC’s regional director, Sophie Orr, said.

Kidnappings have become regular risks, not just for aid workers but for everyone living in Haiti. A gang kidnapped a group of missionaries In October. Some were freed after a ransom was paid. The others said they managed to escape.

Three aid workers were also kidnapped last year, but many aid officials who spoke to The New Humanitarian declined to give details on incidents involving their organisations for security reasons.

A week-long truce announced in mid-November by Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, leader of the G9 federation of gangs, provided some respite to NGOs: Roadblocks were lifted along key roads connecting the capital and the international airport to the southern peninsula.

But many also fear Cherizier: A former police officer who had close links to Moïse, he was sanctioned by the US Treasury for his alleged role in a 2018 attack against anti-government protesters during which 71 people were killed and at least seven women raped.

Because the security situation in the Caribbean country has been so unstable, the World Food Programme has been redirecting some aid from the main hubs in the capital through air transport or via barges to other sea ports. For instance, a helicopter and a small plane operated by the United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS), and managed by WFP, delivers aid daily to Carrefour.

But there are no guarantees that gangs won’t stop even these deliveries. And not all relief organisations can afford to pay for shipping via barges or planes. Many also lack the funds to pay for security guards.

- The New Humanitarian report