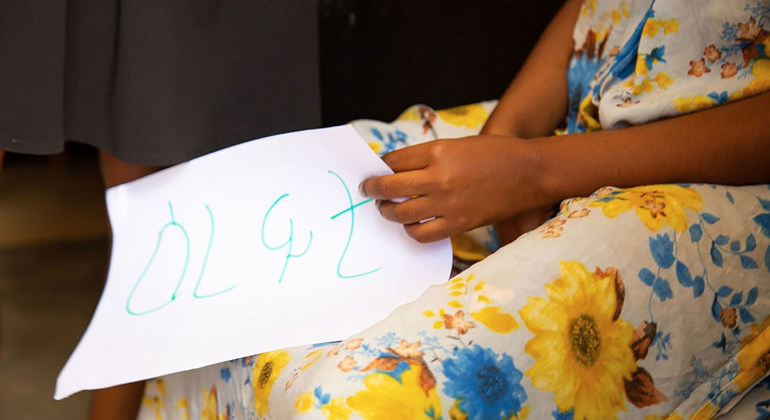

Since the beginning of the war in Tigray in November last year, more than 1,300 incidents of rape have been reported, while many argue that more cases went unreported due to societal stigma surrounding the topic.

A high number of cases of gender-based violence including gang-rape and other atrocities were reported in the period of the conflict. The damage and looting of healthcare facilities in Tigray, Amhara and Afar regions made it worse for the victims impeding the provision of comprehensive after care.

According to the UN, violence against women rises during crises, conflicts and by 2021 one out of every three women have reported being abused during their lifetime. Last November, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights published a joint investigation into alleged violations of international human rights in the ongoing conflict in the Tigray region.

The report revealed that all the fighting forces including Ethiopian and Eritrean forces were involved in crimes designated as gender-based violence with young and elderly women facing incidents of gang rape.

Gender-based violence is a crime that has not been given priority. The New Humanitarian interviewed Lisa Shannon, a co-founder of the group of a new global initiative called Every Woman Treaty about a draft accord prepared by a coalition of women’s rights activists and organisations from 128 countries. The document has been in the works for eight years.

The New Humanitarian: How do you reconcile the different approaches?

Shannon: The call for the global treaty will need to come from the developing world and the Global South. The call for this treaty cannot originate in Europe. We fully expect Europe to be powerful voices in the treaty when negotiations open, but in order for it to be widely adopted, it would have to be celebrated around the world. It will be very important that there be diverse voices. We have been very methodical in identifying potential champions which may be leading the charge.

The US and Canada, in particular, have been very clear that for the treaty to be successful, it cannot have a colonial flavour to it. There is a lot of interest in the Global South to lead that call.

The New Humanitarian: Where have you seen the greatest resistance to such a treaty? Does it come from where we would most expect it?

Shannon: Quite the opposite. The greatest resistance has been from European nations, which say that CEDAW should be interpreted and understood to include violence against women, and that to call for more would undermine CEDAW. The tricky part of this argument is that Europe already has a regional GBV convention (the Istanbul Convention), demonstrating that CEDAW was not enough in Europe. Yet some European nations maintain that CEDAW would be enough for the rest of the world. But it is not adequate.

There is quite a big difference between the human rights climate under a Biden presidency versus a Trump presidency. There is a more open and engaged willingness to progress under the current US administration. It is a lovely window for us to move forward with strong language.

The New Humanitarian: What have the biggest challenges been in drawing up the draft?

Shannon: One of the pieces which I think will be most controversial is whether one can use the framework of gender-based violence versus violence against women and girls. The most progressive nations have articulated why one should pursue a dialogue by using the framework of gender-based violence. But what we have heard from African nations, Latin American nations – even Middle Eastern nations – is that everyone is against violence against women, and widespread support would be expected if the treaty focuses [just] on that.

The minute the word gender enters a dialogue, some regions would get up and leave the room during international talks. This is important, because we feel strongly as a coalition and nations that the actual safety of women and girls, if we can secure that, far overrides the question of whether or not we use the term gender-based violence versus violence against women and girls.

It is widely acknowledged now that there is a normative gap that needs to be filled. From our perspective, CEDAW’s general recommendation 35 on GBV has very strong language, and the idea that that could be developed into an additional protocol is something that we would actually back.

However, three issues remain with that. Around the world, CEDAW’s discrimination framework is a problem, as it creates additional legal barriers – because violence against women is its own human rights violation. Russia, for instance, does not accept that violence against women can fall under CEDAW.

We are also very hopeful that a stand-alone treaty will catalyse a tenfold increase in global funding to end violence against women and girls. It is widely acknowledged that there has been a funding crisis within the human rights treaty system. It is very unlikely an additional protocol to CEDAW would generate the resources needed to implement the treaty.

The draft treaty is an implementation-first treaty. It can be argued that, under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everything is covered. But the nature of human rights law is to get more specific, and this is a natural extension of that.

The third component that would be a remit with the additional protocol of CEDAW is the monitoring system. Right now, it’s a narrative case-monitoring system, and that’s a problem – because nations are reporting against 20 different systems, and violence against women may only get a paragraph or two. That is not enough to address the most widespread human rights violation globally.

We would like to see narrative-based reporting as well as metrics-based reporting – that could resemble the tobacco treaty. It would also borrow from the Paris [climate] Agreement’s ratcheting mechanism, so that nations may get started with what they can get done initially, before advancing from there, so that their progress is measured and celebrated.

The New Humanitarian: Lack of resources is often cited as an impediment to responding to gender-based violence. How key is finance?

Shannon: It’s fundamental. Nepal and Guatemala are nations which passed very strong laws. Clearly, there is always room for improvement, but, in Guatemala, a 2005 femicide law was passed and, in Nepal, multiple laws were passed and the government has been very committed. But implementation is lacking and, in many places, the police aren’t even aware of the law. When you drill down on where the gap is, it’s financial, it’s economic. Nepal is just stuck because there is not enough funding to scale basic proven intervention.

According to a study by the Equality Institute, the total global investment in prevention of violence against women in recent years was only $408 million, or about 11 US cents for every woman. It’s horrifying. Increasing that to address the most widespread human rights violation in the world is just basic dollars and cents, especially when it is costing $4.7 trillion a year, or 5.5 per cent of the global economy. It makes no sense that we aren’t spending that money.

The New Humanitarian: What is keeping this from happening?

Shannon: Lack of priority, full stop.

- The New Humanitarian report