Players in the clean energy revolution are increasingly caught in a cycle of exploitation and greed over resources. At the centre of it is the quest for a prized metal: cobalt, a key ingredient in electric cars.

It’s a different story for the artisanal sector, where Albert Yuma Mulimbi – a long-time power broker in the Democratic Republic of Congo and chairman of a government agency that works with international mining companies to tap the nation’s copper and cobalt reserves – plans to focus the bulk of his stated reforms.

Consisting of ordinary adults with no formal training, and sometimes even children, artisanal mining is mostly unregulated and often involves trespassers scavenging on land owned by the industrial mines. Along the main highway bisecting many of the mines, steady streams of diggers on motorbikes loaded down with bags of looted cobalt – each worth about $175 – dodge checkpoints by popping out of sunflower thickets.

Unable to find other jobs, thousands of parents send their children in search of cobalt. On a recent morning, a group of young boys were hunched over a road running through two industrial mines, collecting rocks that had dropped off large trucks. Workers crushed cobalt-laden rocks to test their purity.

The work for other children is more dangerous — in makeshift mines where some have died after climbing dozens of feet into the earth through narrow tunnels that are prone to collapse.

Kasulo, where Yuma is showcasing his plans, illustrates the gold-rush-like fervour that can trigger the dangerous mining practices. The mine, authorised by Gécamines, is nothing more than a series of crude gashes the size of city blocks that have been carved into the earth.

Once a thriving rural village, Kasulo became a mining strip after a resident uncovered chunks of cobalt underneath a home. The discovery set off a frenzy, with hundreds of people digging up their yards.

Today, a mango tree and a few purple bougainvillea bushes, leftovers of residents’ gardens, are the only remnants of village life. Orange tarps tied down with frayed ropes block rainwater from flooding the hand-dug shafts where workers lower themselves and chip at the rock to extract chunks of cobalt.

Georges Punga is a regular at the mine. Now 41, Punga said he started working in diamond mines when he was 11. Ever since, he has travelled the country searching Congo’s unrivalled storehouse for treasures underfoot: first gold, then copper, and, for the past three years, cobalt.

Punga paused from his digging one afternoon and tugged his dusty blue trousers away from his sneakers. Scars crisscrossed his shins from years of injuries on the job. He earns less than $10 a day — just enough, he said, to support his family and keep his children in school instead of sending them to the mines.

On most days, hundreds of men trudge into this mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo wearing plastic headlamps and hoisting shovels in search of treasure underground: cobalt.

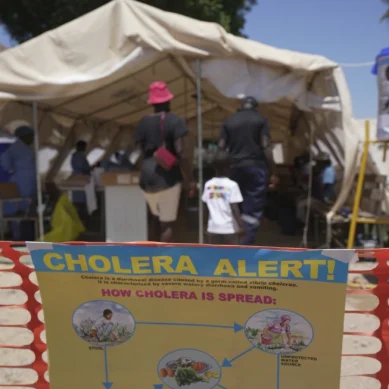

Officials in Congo have begun taking corrective steps, including creating a subsidiary of Gécamines to try to curtail the haphazard methods used by the miners, improve safety and stop child labour, which is already illegal.

Under the plan, miners at sites like Kasulo will soon be issued hard hats and boots, tunnelling will be forbidden and pit depths will be regulated to prevent collapses. Workers will also be paid more uniformly and electronically, rather than in cash, to prevent fraud.

As chairman of the board of directors, Yuma is at the centre of these reforms. That leaves Western investors and mining companies that are already in Congo little choice but to work with him as the growing demand for cobalt makes the small-scale mines, which account for as much as 30 per cent of the country’s output, all the more essential.

Once the cobalt is mined, a new agency will buy it from the miners and standardise pricing for diggers, ensuring the government can tax the sales. Yuma envisions a new fund to offer workers financial help if cobalt prices decline.

Right now, diggers often sell the cobalt at a mile-long stretch of tin shacks where the sound of sledgehammers smashing rocks drowns out all other noise. There, international traders crudely assess the metal’s purity before buying it, and miners complain of being cheated.

Yuma led journalists from The Times on a tour of Kasulo and a nearby newly constructed warehouse and laboratory complex intended to replace the buying shacks.

“We are going through an economic transition, and cobalt is the key product,” said Yuma, who marched around the pristine but yet-to-be-occupied complex, showing it off like a proud father.

Seeking solutions for the artisanal mining problem is a better approach than simply turning away from Congo, argues the International Energy Agency, because that would create even more hardships for impoverished miners and their families.

But activists point out that Yuma’s plans, beyond spending money on new buildings, have yet to really get underway, or to substantially improve conditions for miners. And many senior government officials in both Congo and the United States question if Mr. Yuma is the right leader for the task – openly wondering if his efforts are mainly designed to enhance his reputation and further monetize the cobalt trade while doing little to curb the child labour and work hazards.

Bottles of Dom Pérignon were chilling on ice beside Yuma as he sat in his Gécamines office, where chunks of precious metals and minerals found in Congo’s soil were encased in glass. He downed an espresso before his interview with The Times, surrounded by contemporary Congolese art from his private collection. His lifestyle, on open display, was clear evidence, he said, that he need not scheme or steal to get ahead.

“I was 20 years old when I drove my first BMW in Belgium, so what are we talking about?” he said of allegations that he had pilfered money from the Congolese government.

Yuma is one of Congo’s richest businessmen. He secured a prime swath of riverside real estate in Kinshasa where his family set up a textile business that holds a contract to make the nation’s military uniforms.

A perpetual flashy presence, he is known for his extravagance. People still talk about his daughter’s 2019 wedding, which had the aura of a Las Vegas show, with dancers wearing light-up costumes and large white giraffe statues as table centrepieces.

He has served on the board of Congo’s central bank and was re-elected this year as president of the country’s powerful trade association, the equivalent of the US Chamber of Commerce.

- The New York Times