Uganda has a long history of institutionalised violence. This forms the central theme of President Yoweri Museveni’s on African politics, What is Africa’s Problem? in which he blasts megalomaniacs who worm their way into power promising heaven before they turn their counties into hell.

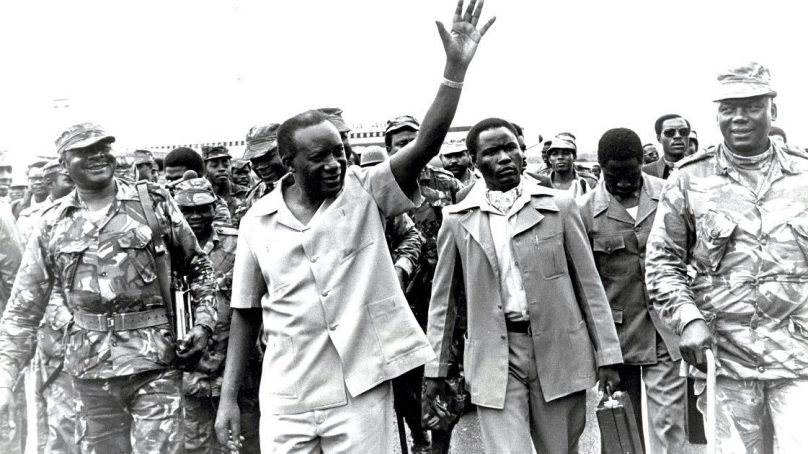

President Museveni himself is a case study on how why and how African presidents overstay their welcome and resort to the use of violence in varied forms to cling onto power. It all started at a meeting at a house in Kabete, Nairobi, between Prof Yusuf Lule and Museveni, who had joined forces to run President Milton Obote out of town. Museveni went on to overstay his welcome.

In their article titled Institutionalised Violence, S.C. Cersele and A.V. Haecht of the Centre of Sociology of Law and Justice (Institute of Sociology – Free University of Brussels) describe intellectualised, institutionalised or institutional violence as follows:

“Institutional violence is an established form of interpersonal violence resulting from the existence of such institutions as the police and prisons and from the practices of repressive justice. Such violence emanating from institutions which exercise power may manifest itself in the political, the economic, and the cultural spheres.

Counter-institutions and counter-violence may develop in reaction to the institutional violence. In the political sphere, violent institutions such as prisons exist in all political regimes. In this context, counter-institutional violence may take the form of riots, revolutions, airplane hijackings, kidnappings of diplomats and permanent terrorism. Institutional violence in economic fields may result from coercion, competition, stock market speculation, new forms of credit, professional associations and unions.

These various types of violence may be counteracted with strikes, sabotage of production, plundering of luxury department stores and various types of work stoppage. Cultural violence may be manifested as various forms of mass media and films, censure of permanent education; counter-institutional violence occurs as cultural revolution but is in general rare. It is concluded that some form of institutional violence is inevitable in almost any regime, and that the violence of any institution is likely to provoke counter-violence.”

In the treatise published in and published in 1980, Cersele and Haecht did not include the primitive accumulation of wealth by people in power at the expense of providing public goods and services as violence against the people.

This particular article reveals that virtually all presidents in Africa who come to power – mostly violently – when they are poor and overstay through turning the instruments of power against the people, or manipulating the electoral processes in their favour, end up being among the wealthiest in the countries they rule or even in the whole world.

Africa today boasts of the biggest number of overstayed rulers in the world who are also stinkingly wealthy.

Forty years ago, President Tibuhaburwa Museveni published What is Africa’s Problem? in which he discusses the continent’s problems in terms of overstayed rulers he called leaders. Museveni answers the question thus: “Leaders who overstay in power”. By the time the book was published, Uganda hadn’t had a leader who had been in power for a long time.

Only the colonialists had really overstayed in power (for 70 years). Apollo Milton Obote, who ruled Uganda twice, had ruled Uganda for 9 years, interspersed by three years of the ceremonial presidency of Sir Edward Mutesa II, when Idi Amin overthrew his government on 25th January 1971. Idi Amin himself ruled Uganda for eight years before the combined Obote, Museveni and Tanzanian militaries forced him out of power in 1979. Yusuf Lule who took over immediately after the overthrow of Idi Amin lasted only 63 days in the office of president of Uganda. Godfrey Binaisa who succeeded him lasted only 11 months in office.

The de-facto presidency of Paulo Muwanga lasted a few days before Obote assumed the presidency of Uganda again in December 1980. However, Yoweri (Tibuhaburwa) Museveni detested another reign by Obote and by February 1981 he was in the bush as Patriotic Army (PRA) to fight Obote’s nascent regime and possibly remove it through the barrel of the gun.

The PRA was assembled mainly by the Front for National Salvation (FRONASA), which was formed by Yoweri (Tibuhaburwa) Museveni and was dominated by Rwandese refugee elements and some Banyamulenge elements (Tutsi elements from Mulenge area of the Democratic Republic of Congo) The fighting group constituted a contingent of the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) of the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF).

The other contingent of UNLA was constituted by Obote’s Kikosi Maalum, which was commanded by soldiers like Oyite Ojok (a Lang’i) and Tito Okello (an Acholi). These and other soldiers of Kikosi Maalum, created by UNLA’s military commission, whose chairman was Paulo Muwanga and vice-chairman was Yoweri (Tibuhaburwa) Museveni.

The military commission wielded a lot of power and could overrule decisions made by UNLF’s legislative arm called National Consultative Council (NCC) constituted by a diversity of political camps, many non-ideological.

In effect, when Yoweri (Tibuhaburwa) Museveni wanted to form the nucleus of PRA, he simply withdrew his men in their thousands from the UNLA, strategically leaving a few in the UNLA, which Obote’s new regime had to depend on for its security.

With FRONASA elements still in the UNLA, it was a matter of time before their destabilising impact was felt by the Obote regime since they were linked to the PRA. Although as a politician Obote used to talk tough, including “If Museveni goes to the bush, we shall pursue him and leave him there”, he knew the army subtending his power was not a unified whole, was greatly infiltrated by former FRONASA elements, and was, therefore, potentially and actually unstable.

The FRONASA elements were like parasites eating up UNLA. The Langi-Acholi differences made it worse, undermining its solidarity and capacity to face, in the medium-term, the challenges of rebellion by a well-organized, purpose-driven military outfit, which PRA was.

When PRA combined with Yusuf Lule’s Freedom Fighters (FF) to form National Resistance Army (NRA) and the National Resistance Movement (NRM), a political organisation originally formed by Baganda neo-traditionalists in Kabete, Nairobi, rebellion against the nascent regime of Obote crystallised, militarily and politically.

A long insurgency under the military command of Yoweri (Tibuhaburwa) Museveni combined with the internal wrangles within the UNLA between the Lang’i and Acholi elements weakened Obote’s second regime so much that it could not concentrate effectively on rehabilitating and reconstructing the country beyond the destructive effects of Idi Amin’s rule.

The insurgency, which the combatants erroneously called liberation (of Ugandans) focused its military might on destroying whatever economic, development, transformation or progress was being made by the regime. Cooperatives, banks and union were robbed by the combatants who turned Luwero Triangle (consisting of 22 districts) into a theatre of war with the UNLA and the FRONASA army.

Railway lines and bus transport companies were disabled and factories and/or industries ransacked by the combatants.

Meanwhile the combatants built a very effective propaganda machine to depict Obote and his regime as anti-people bent on massacring people. It was a matter of time before Obote’s regime government was overthrown in July 1985 by Acholi elements in the UNLA, led by Tito Okello and Basilio Okello. It lasted just about four years. The new regime was called the Okello Military Junta. Paulo Muwanga was its immediate prime minister but was soon was succeeded by Paulo Ssemogerere. Olara Otunnu was the Junta’s foreign minister.

- A Tell report / By Oweyegha-Afunaduula, a former professor of environment at Makerere University, Uganda