This December, it’s cold and we’re constantly hungry, so we’re thinking about cooking. Also, yes, we’re going to get into the Graham Hancock Netflix series. You knew it was coming.

At this time of year, as the temperatures drop and the rain is near-constant, I find myself always craving pies. I don’t know what unrecognised geniuses invented pastry and then had the idea to put a casserole inside it, but I owe them an unpayable debt.

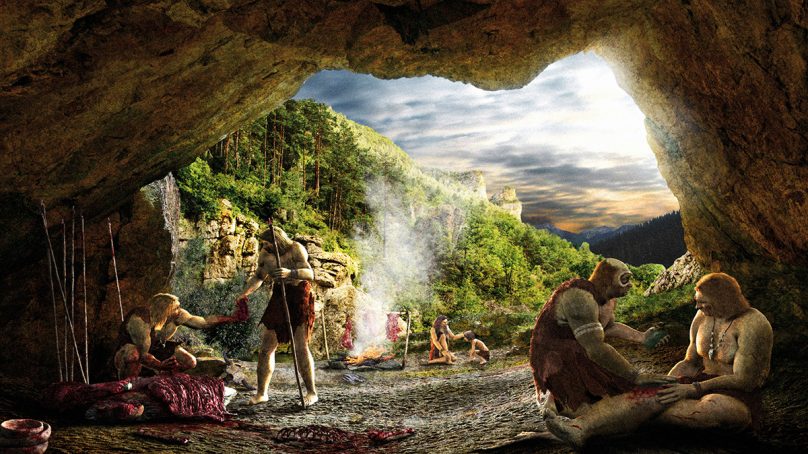

So, let’s talk about the invention of cooking. How long have humans been deliberately exposing their food to heat to make it better?

You might remember a story from mid-November reporting evidence that hominins were cooking carp fish in an earthen oven around 780,000 years ago in what’s now Israel. The find demonstrated the antiquity of cooking: previously, the oldest unambiguous evidence of cooking was from 170,000 years ago in South Africa.

What’s more, the baked carp predates our species Homo sapiens by hundreds of thousands of years. The chefs must have been Neanderthals or other extinct hominins. This is supported by another study from November, reporting pulses that had been pounded and charred at Franchthi Cave in Greece and Shanidar Cave in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

These sites are more recent, within the last 100,000 years, but the Neanderthals are still the most plausible candidates for the cooks.

In other words, we now know for certain that cooking is not unique to our species and that it was going on three-quarters of a million years ago. What’s more, ovens are a fairly advanced form of cooking, compared to simply holding your food over a fire. To me, that’s a hint that cooking goes back even further.

For over 20 years, Harvard biologist Richard Wrangham has been promoting the hypothesis that hominins started cooking around two million years ago. That’s not long after our genus Homo evolved. Crucially, it’s when brains evolved to be much bigger. Wrangham argues that cooked food, which is both more nutritious and easier to chew, enabled the evolution of large brains.

When Wrangham first suggested it, this was a big swing because hard evidence of cooking was confined to relatively recent periods. However, absence of evidence isn’t necessarily evidence of absence. The most obvious traces of cooking are organic remains, which tend to decay – unlike resilient things like stone tools. The age of the oldest evidence of cooking doesn’t necessarily tell us when cooking started: it tells us about how easy it is for evidence of cooking to be preserved.

In line with this, as the years have passed, the evidence of cooking has been pushed further back. Traces of ash and burned bone from a cave in South Africa hint at cooking one million years ago, and a site in Kenya has evidence of hominins roasting meat over fires 1.5 million years ago. The new studies add to the evidence for ancient cooking.

The evidence for cooking sits alongside the growing evidence for controlled use of fire by extinct hominins. The tricky thing about the archaeological record of fire is that fires happen all the time anyway. Researchers must discern fires started and controlled by humans from ordinary forest fires and the like.

Back in 2011, a systematic review found that controlled fire use could be traced back 400,000 years. That’s before the origin of our species, so Neanderthals (and possibly other hominins) could control fire. But it’s a long way from two million years ago.

However, the evidence is again being pushed back. Back in June I was delighted to read Colin Barras’ story about evidence of controlled fires one million years ago, again in what’s now Israel. I wasn’t so much excited by the date, even though it gets us halfway to Wrangham’s date.

Instead, the key thing was the method. The team studied flints that showed no visible sign of having been heated.

Careful examination of their response to UV light showed that their crystal structure had been altered by heating to around 400°C. This form of evidence could be far more widely preserved and has the potential to demonstrate that Homo had control of fire two million years ago.

I should also mention the report last week that Homo naledi, ancient humans that lived in what’s now South Africa, may have used fire to cook and to navigate in dark caves. The evidence for this comes from the Rising Star caves where the species’ bones were found.

Deep in the caves, there are “huge lumps of charcoal, thousands of burned bones, giant hearths and baked clay”, according to Lee Berger at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa who led the research.

That’s certainly dramatic, but it comes with a colossal caveat: the team hasn’t dated this stuff yet, so it might be nothing to do with H. naledi.

H. naledi lived relatively recently, between 230,000 and 330,00 years ago, so their putative fire use wouldn’t extend the period in which hominins have controlled fire and cooked. However, H. naledi had small brains for such a recent hominin, so if they could do it, maybe even earlier hominins were capable of it.

We can get some clues about the earliest hominins’ relationship with fire by looking at modern ape behaviour. A study published in April showed that savannah-dwelling chimpanzees often prefer to travel in regions that have recently been burned, and that they find more food in those places – perhaps because concealing undergrowth has been burned away.

It’s not hard to imagine hominins shifting from this passive use of fire to something more active. But when they did so remains wildly uncertain.

Taken together, all these studies have swayed my opinion about the cooking hypothesis. I’m still not convinced Wrangham is right, because we don’t have evidence of cooking as early as Wrangham needs it, but my internal needle of scepticism has shifted.

And now I want a pie.

- A New Scientist report