A fine wine can be a lot of things: oaky, fruit-forward, maybe even chewy. But wines of recent vintage also have the bouquet of a logistical nightmare, due to a brutal convergence of natural and human-made crises: drought and extreme heat, plus lingering supply chain hang-ups that have made it harder to get glass, cork, the aluminium for screw caps, and the metal capsules that wrap the tops of bottles.

Winemaking is a delicate agricultural ballet embedded within a delicate logistical ballet, and both ballets are going off script simultaneously. “It’s a perfect storm,” says UK-based wine importer Daniel Lambert. “Most people don’t think about raw materials that are involved in wine production.

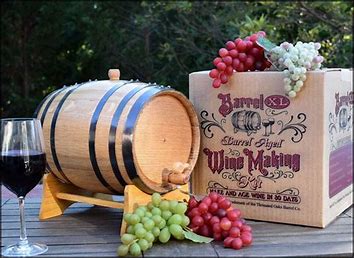

Obviously, you’ve got the grapes – everybody gets that bit. But people forget that you have a bottle, you have a cork, you have a capsule.” Prices for all of those have been rapidly inflating, which translates to higher wine prices.

For example, a rosé bottle may seem like a simple vessel for transporting fermented grape juice into a glass. But presentation matters: People want to see that nice pink colour through clear glass. Bottle colour isn’t much of an issue for red wine – that looks just fine in a dark green container. But clear glass can cost twice as much to produce, Lambert says, because it requires more purification, which requires more energy, which requires more money. It’s extra expensive for European manufacturers now due to the skyrocketing energy prices that have followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Which bottle a winemaker can choose is also subject to legal rules and physics parameters. Sparkling wines like champagne require thicker – and therefore more expensive – glass to contain the pressurised liquid. And some geographic regions mandate that a certain kind of bottle be used for a certain kind of wine, so a producer can’t just switch to a cheaper alternative.

In winemaking, timing is everything. Unlike a beermaker, who can brew year-round, a vineyard completes one harvest a year, so the operators need to plan ahead for a shipment of bottles. And due to glass shortages, now they have to plan way ahead.

“The biggest impact that we’ve seen with supply chain disruption is just a dramatic increase in how far ahead we have to order it,” says Jon Ruel, CEO of Trefethen Family Vineyards in Napa, California. “Something like glass, which used to be six to eight months, is now like 12 to 18 months. We haven’t even picked the grapes yet. We don’t know how much wine we have. But we have to decide how much we need.”

The market for corks that go into those bottles has also gotten messy. Cork trees are a kind of oak native to the Mediterranean, and the material is harvested by carefully pulling the extra-thick bark off the tree without killing it. This process is repeated every nine years as the bark grows back. Portugal, which is home to a third of the world’s cork forest area, processes the bark into wine stoppers and ships them abroad. Then a company like Cork Supply USA prints a winery’s branding on them and adds a surface coating.

Greg Hirson, that company’s vice president of product, says that while there isn’t a cork shortage now, climate change is making the supply less predictable. In times of drought, the trees get too dry to pull off the bark without damaging the underlying tissues and killing the plant.

“So maybe we have to leave the bark for another year until we have a slightly wetter season,” says Hirson, or producers might not be able to extract as much as expected from a given forest.

Pandemic-related shipping issues have also put a hiccup in the cork supply chain. It used to take around 27 days to get them from Lisbon to the Port of Oakland in California and into the Cork Supply USA warehouse. That regularity allowed the company to plan out how much material it would need to fulfill orders for wineries. But no longer.

“At its worst – which I would say was probably April, March 2022 – we were at like 130 days, but plus/minus 60,” says Hirson. “Sometimes the stuff would show up four weeks before we were expecting it, and sometimes it would show up three weeks after we were expecting it. So the ability to plan just totally went out the window.”

- A Wired report