Kargi is an isolated settlement, two-hours’ drive from the northern Kenyan town of Marsabit, across an ancient volcanic plain of jagged scree and basalt rock.

As inhospitable as the terrain seems, Kargi does have a borehole, and that makes it something of an oasis for pastoralists trying to get their livestock through the second year of a punishing drought.

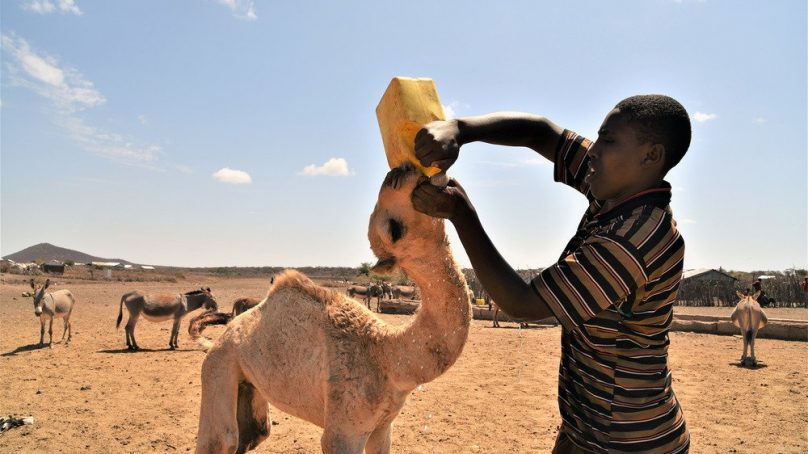

Pastoralism – herding livestock as opposed to farming a set piece of land – is a highly efficient way of living in the harsh drylands. For the wiry Rendille men gathered at the borehole, a few kilometres from the settlement, it’s both an agricultural system and way of life.

But as the climate becomes more and more unpredictable, the sustainability of the traditional model – and the customs that underpin it – are increasingly in doubt.

World leaders gathered at COP26 in Glasgow last week promised new emissions-cutting targets for decades in the future, but the reality for Kenyans living in the drylands is that these pledges have come too late.

On average, the Kargi men have lost half their livestock to drought this year – on top of the failed rains last year, made worse by swirling swarms of locusts that munched through remaining pasture. You can smell the dead animals off in the dry scrub where their carcasses were dragged, their resistance spent.

“If it rains now, the animals will have something to sustain them,” said Nakoridor Sigalen, thick silver rings in each ear. But the forecast is that this season’s October-December rains will be poor again – and could fail in March-May 2022 as well. Then what? “Our survival is in God’s hands,” he eventually responded.

More than 2.4 million people are struggling to feed themselves in Kenya’s 10 worst drought-hit northern and southeastern counties. Among them are 368,000 people at “emergency” levels of hunger, a technical term to mean nutrition-related deaths in some households if there are no assets to sell.

In Kargi’s small health post, nurse Sabina Laribi says seven out of the 10 children she screens have signs of malnutrition. “Rates are rising because 90 per cent of the families here depend on their livestock,” she said. “In the three years I’ve been here, this is the worst I’ve seen.”

Those needs are magnified by both a breakdown in supplies of the high-calorie therapeutic food used to treat the children, and a lack of transport to get out to the more far-flung settlements, which has hamstrung the supplementary feeding programme she runs.

It’s not only drought that threatens lives. Hardship is sharpening ever-present competition between armed pastoralist communities, triggering a tit-for-tat spiral of clashes.

Mohammed had already lost 100 animals to the drought: The attacks claimed another 50.

There’s little water and pasture around the rocky outcrop where the families have pitched their tents of plastic sheeting and built pens for their remaining livestock. They’ve been there for a few weeks and intend to stay. “I’m going to wait for the rains – I’m too scared to go back,” he said.

Most of the young men from Gutu have moved to Isiolo to try and hustle for a living. Some sold their livestock, bought motorbikes and have become “boda-boda” taxi riders. “It’s better than being killed,” Mohammed said.

The so-called Arid and Semi-Arid Lands have historically been neglected by the rest of Kenya, where political and economic power is based on the heavily populated farming regions further south. But devolution in 2013 triggered a surge of growth in the ASAL counties.

The downside has been a spurt of settlements, encouraged by local politicians looking to grow their vote banks. But the more settlements there are, “the less land there is for pasture,” said Hussein Noor, livestock systems expert with the aid agency Mercy Corps.

The proliferation of unplanned boreholes has contributed to overgrazing that has damaged an already fragile ecology, encouraging the spread of livestock diseases.

Fenced off conservancies, linked to high-end tourism and backed by a number of foreign-based NGOs, is offered as a model to better manage the rangelands. But the common local complaint is that they prioritise the well-being of wildlife rather than the communities they claim to support – denying access to pastoralists even in times of crisis.

For conservative pastoralists like Sagalen in Kargi, animals are traditionally more than an economic asset – they’re also a measure of social standing: “You need more livestock to have a better life,” he explained.

But the back-to-back droughts have delivered a painful lesson: The bigger the herds, the harder it is to keep all the animals alive and healthy.

“The better coping strategy is to sell off animals before prices crash, and then use the money to restock after the drought, with a smaller number,” Noor said. “You can then use the income to vaccinate, and improve your breeds.”

The logic is not lost on Sagalen. He has already exchanged his prized cows for hardier camels that can go far longer without water.

“The culture is in transition,” said Ibrahim Muroya, who has managed the borehole in Kargi for 17 years. “People are not into the old way of life completely, but they also haven’t fully transformed.”

- The New Humanitarian report