Background

It is now universally accepted that “learning is the new form of labour. It is no longer a separate activity that occurs either before one enters the workplace or in remote classroom settings.

Learning is the heart of productive activity (Shushans Zuboff, In the Age of the Smart Machine, cited by Peters, 1992). It is, therefore, important that Knowledge Management is taken seriously. “Soft” now dominates. “Hard” has been eclipsed (Peters, 1992: 382). Bringing knowledge to bear quickly is critical, and learning from one another, either as individual human beings or individual organisations, can no longer be undervalued or underestimated (modified from Peters, 1992). The focus is on learning organisations.

Things have changed. Knowledge management and knowledge integration, and the learning process per se, is markedly different, not only in many universities around the world but also at the workplace, where the balance between knowledge acquisition and transmission and creativity and innovation on the one hand and serving clients and creating knowledge on the other (modified from Peters, 1992) has become the norm rather than the exception. At workplaces the new trend is to take every engagement as a learning opportunity (e.g., Manville, cited by Peters, 1992:386). This is what Manville, cited by Peters) further says:

“…. Very smart analysts are no longer a scarce resource, and just throwing very smart people at a problem…is not enough anymore. Professionalism…plus consultant skills plus institutional knowledge equals client impact” Manville, cited by Peters, 1992: 386). As Peters (1992) notes, emphasising systematic development of consultant skills beyond catch-as catch-can is new, and putting institutional knowledge development and application on a par with the other two amounts a dramatic shift in emphasis.

This development is a result of the worldwide trend of de-emphasising knowledge acquisition and transmission and re-emphasising knowledge reintegration, creativity and innovation. It is no longer fashionable to fragment knowledge and knowledge production, confining knowledge seekers in small knowledge cocoons called disciplines, with almost no interaction with others in different knowledge cocoons, who only interact casually. The idea of individual institutional learning through knowledge was alien almost three decades ago (modified from Manville, cited by Peters, 1992: 386).

According to Manville, cited by Peters, knowledge development is a professional responsibility; putting people in touch with one another is no longer a casual, personal process, is becoming more systematised and the overall knowledge-building process will allow people to extend their personal networks fast and efficiently. This is the way forward to fast and efficient management of knowledge, new it allows everyone involved in knowledge production to become more involved, get his or her name around more extensively, more valuable, better positioned to be recruited for better assignment, and to be much broader in knowledge and practice exposure. You continually remain current (modified from Manville, cited by Peters, 1992: 387).

All this is the consequence of new knowledge production, which remains alien in African and East African Universities. Here the focus is still on individual academic growth, achievement and recognition, with renewed and increasing emphasis on knowledge fragmentation, knowledge acquisition and knowledge transmission and diminished emphasis on creativity and innovation.

It is against this background that this article has emerged. Hopefully, sooner than later, it will stimulate a rethinking of education systems, knowledge organisation, production and management for critical thinking, critical analysis, openness, accommodation, creativity and innovation for our universities to remain relevant.

The science of listening and learning together, which characterised the teaching and learning during the times the great ancient teachers – Plato, Aristotle, Socrates and even the greatest of the greatest teacher, Jesus Christ – as well as teamwork across the board need to be reintegration in the teaching, learning processes. The new knowledge production demands that this be the case.

The evolution of new thinking on knowledge in East Africa

Professor Bethwell Allan Ogot has discussed the imbalance between the two tendencies with reference to Kenyan universities. He notes that the universities in Kenya are laying too much emphasis on knowledge acquisition and transmission and minimal emphasis on creativity and innovation. But isn’t this the same crisis at our more than 50 universities in Uganda?

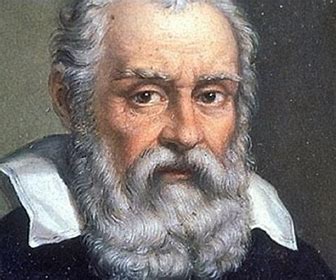

In his Book Who If Anyone Owns The Past? Reflections on The Meaning of Public History published in 1992 by Anyange Press of Kisumu, Kenya, Prof Ogot, allocates a whole Chapter 10 on “Rediscovering Galileo or Who is Qualified to Teach in A University”. The Chapter is based on a lecture he delivered at the Commission for Higher Education Stakeholders Workshop on “Enhancing Quality Higher Education in Kenya at Kenya College of Communication and Technology on August 13, 2008. That was almost 11 years ago. He wondered why the organisers of the workshop found it necessary to invite him to discuss a question on which there is already unanimity among the stakeholders: that for one to teach in a Kenyan university one must have a PhD degree in a relevant field. He, however, observed that in all the universities in Kenya some teachers with masters qualifications have been allowed to teach and even supervise masters students.

While agreeing that a PhD or equivalent should generally be necessary for teaching in a University if quality in higher education is to be enhanced and a cadre of committed teachers, researchers, intellectuals and intellectual leaders produced, Prof Ogot says that higher education must go beyond simply a concern for individual or national economic competitiveness. He is of the view that higher education must engage in and stimulate others to engage in widely philosophical and social issues of the public good. He adds:

“With increasingly complex societies, integrating into an increasingly complex and competitive world, it is essential for every country to have a large and growing cadre of highly skilled professionals, thinkers, actors, writers and teachers in a wide range of fields who are capable of producing critical analyses, policies and programmes to deal with the internal and external social and cultural issues facing their nation. African universities should provide the ideal location for such skilled professionals…..Our Universities today need an infusion of new self-confident, committed and well-trained scholars, specifically charged to bring to their department s new energy, new confidence, new approaches and new pedagogies.. university teachers should be those who can find new problems in old ones; those who can think divergently instead of convergently, and those who can solve problems in creative ways”.

Knowledge production and management in medieval Europe

Prof Ogot decries the crisis of creativity and innovation vis-à-vis knowledge acquisition and transmission in our universities. He observes that the crisis characterised Universities in the Medieval times in Europe, but now our universities are its hotbed. He demonstrates the crisis by citing the agony, trials and tribulations of Galileo Galilei who at the age of about 20, and a fresher at university could not just take what his professors were telling him.

Galileo Galilei deplored the academic practice of his professors of always hyping Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen as the unchallengeable authorities in the academia. It was taboo to question those three authorities in the academia. They were the beginning and end of knowledge. Galileo wanted to hear the voices of his professors reflecting their own thoughts, not those of ancient thinkers.

Galileo was a young great thinker who questioned every statement of his professors at the University of Pisa in Italy. He was doing medicine, but to the chagrin of his father who did not want him to leave medicine, he decided that he was leaving medicine because his professors were not thinkers but only cited ancient authorities and regurgitated their thoughts.

Ogot says that when Galileo’s father refused him to leave medicine, he decided to teach himself mathematics, which he loved, while continuing with the boring professors, but he devoted more of his time on mathematics. If he attended his medical classes he would annoy his lecturers by demanding a reason or proof for every fact they stated.

Those days the lecturers would tell the 20 year old Galileo that what they were telling him was true because the books stated so. And they would do what he did not like – cite Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen.

One time Galileo asked his professors, “You say it is right because it is in the works of Aristotle, but suppose Aristotle made a mistake?”

Ogot says the professors and other students hated Galileo for being too inquisitive and despising ancient authorities. He was treated like a criminal yet he was seeking the truth. He was chased out of class. But one day while observing two swinging lumps in the Cathedral, he shouted, “Aristotle was wrong! Now I can prove that he was wrong”.

When Galileo demonstrated the phenomenon of the lumps using a big and small ball, they swung at the same time and returned to the original position at the same time. According to Ogot, Galileo’s discovery led to many other inventions. Note that the young Galileo had no degree nor any training when he introduced his critical thoughts and made his discovery. Note that even the authorities that his professor cited like parrots did not have degrees. The greatest of the greatest of teachers that the world has been lucky to have, Jesus Christ, did not have a degree either.

The immediate consequence of Galileo’s discovery was for the impressed mathematicians to propose that Galileo, without a degree and without training, is made a professor of physics at the University of Pisa at 25. But his revolutionary ideas irritated the old professors who never challenged Aristotle. They connived and got rid of him from the university. Ogot records that lucky enough for Galileo, a renowned professor of mathematics at the Italian University of Padua passed on in 1592 and he was offered the chair of mathematics. Mind you, without a degree or training in mathematics. And youthful scholars flocked in from Italy, France, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands to listen to the inspiring lectures of Galileo (Ogot, 1992).

Galile, records Ogot, got involved in the movements of heavenly bodies and even invented the compass, which proved useful in military operations. The University of Padua elected him professor for life without a degree or training but lecturing supervising many to reach professorship. He went on to invent the famous telescope while at the University of Padua. In 1616 he was accused by the Catholic Church of contradicting its teaching. Ogot cites Galileo’ defence during his trial thus:

“The scriptures are not a treatise on astronomy, but a message of salvation that does not impinge on the independence of scientific investigation. The intention of the Holy Spirit is to teach us how to get to heaven, not how the heavens work”.

Ogot goes on to tell us that in 1633 Galileo was again accused and confined to his house in Arcetre, and it was there where he achieved even greater fame. He wrote his most original and significant work Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences published in Holland in 1637. The most important statement in the book was “Nothing that cannot be proved should be accepted as dogma”.

Ogot records that Galileo died in 1642 at the age of 78 embracing his (Catholic) faith and science. The good ending to the story of Galileo, according to Ogot, is that on November 10, 1975, on the occasion of the celebration of the century of the birth of Albert Einstein at the Vatican, Pope John Paul II finally admitted: “The man who is rightly called the founder of modern physics, explicitly said that the two truths, that of faith and that of science, can never contradict each other……Galileo’s greatness is known to all, as is Einstein’s; but unlike the latter, to whom we are paying tribute today before the College of Cardinals at the Apostolic Palace, the former, there is no denying this, suffered greatly at the hands of men of the Church and ecclesiastical bodies”.

This, Ogot says, was a rather oblique way of apologising for the grave sins committed by the Catholic Church against one of the greatest scientists. Ogot ends his intellectual exploration of Galileo by asking:

“Who is qualified to teach at a university: one who acquires and transmits knowledge, or who is creative and innovative and can solve problems?”

Answer him. However, let me go on with the article and state what is in my mind and brain.

In a way, Ogot is saying that “to learn to learn” (and by extension to learn to teach), although a matter of course as Peters (1992) puts it, is an enormous task, which requires being broader than we have hitherto preferred to be in our academia. It requires a new sociology (e.g., Peters, 1992) to remove the traditional barriers to more wholesome learning, which unfortunately have been recently re-entrenched in our East African universities (e.g., Ogot, 1992; Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2004). This requires seeing things as a totality, thinking in “wholes” and “metaphors of wholes”(Peters, 1992: 452) and, thus, going beyond hierarchy.

Unfortunately, or fortunately, such an innocent-sounding requirement runs counter to our long-standing penchant for increasing specialisation (Peters, 1992); sometimes overspecialisation. Oweyegha-Afunaduula (2004) discussed the sense and nonsense of specialisation, just before Makerere University decided that specialisation was the way to go in the 21st Century. He suggests that specialisation is an abuse of the mind since it narrows the learner and knowledge producers to a narrow band of knowledge. In the end, nobody knows anything.

Towards new knowledge production

Peters (1992) cites Frank Smith who, in his Insult to Intelligence: The Bureaucratic Invasion of Our Classrooms, writes:

“The myth is that learning can be guaranteed if instruction that is delivered systematically, one small piece at a time, with frequent tests to ensure that students and teachers stay on the track…. Nobody learns anything, or teaches anything, by being submitted to such a regiment of disjointed, purposeless, confusing, tedious activities. Teachers burn out, pupils fall by the wayside, parents and administrators worry about the lack of….progress or interest”.

A survey of recent concerns in the literature regarding integration of knowledge shows that the need for and recognition of more holistic teaching and learning is now a global phenomenon moving like a wild fire, to weed out the knowledge fragmentalists and cast them aside into oblivion. It is now interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, crossdisciplinary and nondisciplinary knowledge, which are moving us to wholeness of knowledge, wholeness of learning, wholeness of teaching and wholeness of human beings streaming out of our learning centres, that is becoming a 21st century imperative.

Definitions

We need to do some defining of the concepts of disciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity and nondisciplinarity. Let us use Augsburg’s (2014) definitions with slight modifications.

* Disciplinarity: Also referred to as intradisciplinarity, is working within a discipline.

* Crossdisciplinarity: Viewing one discipline from the perspective of another.

* Multidisciplinarity: People from different disciplines working together, each drawing on the disciplinary knowledge of the others.

* Interdisciplinarity: Integrating knowledge and methods from different disciplines using a real synthesis of approaches.

* Transdisciplinarity: Creating a unity of intellectual frameworks beyond one’s discipline.

* Nondisciplinary: Knowledge discourse, which does not involve recourse to disciplines of knowledge.

Nondisciplinarity and intradisciplinarity

Life, in its diversity, and the world are not disciplinary, but nondisciplinary. This was the case from the beginning until the Mediaeval times, when scholars started to discipline knowledge and the social relations in the academia by creating pockets of knowledge called disciplines, with rigid walls separating them. Intradisciplinary knowledge production became the rule rather than the exception. A knowledge producer or knowledge worker would only be recognised if his or her knowledge production or work was intradisciplinary. However, cultures and traditions throughout the world remained nondisciplinary. They still do. Indigenous knowledge is thus nondisciplinary. Even during the times of the great ancient thinkers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, knowledge production was nondisciplinary. With the creation of disciplinary know ledge production entities in the academia nondisciplinarity was occluded. If one was nondisciplinary, one did not belong to the world of knowledge.

Fortunately, in the evolving knowledge society, nondisciplinarity is repenetrating the world of knowledge with many networks, which have no respect for disciplines, being created between society, government, industry and academia. The social media are a modern example on nondisciplinarity on the move again.

Interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity

Long ago Jantsch (1972) advocated for the creation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary universities as a systems approach to education. By that time, there was already concern about specialisations encouraged by Intradisciplinarity, within rigidly walled disciplines, where the myth of purity of knowledge was propagated in the university system. Increasingly, greater collaboration across the university curriculum in knowledge creation is being advocated (e.g., Inkpen, 1996; Lattuca, 2001) towards accumulation of more whole knowledge, away from fragmentation of knowledge, which both Intradisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity conserve and perpetuate.

A lot of literature now abounds to show the increasing importance and significance of whole knowledge to the present world, which is drastically different every five years. Richard Crawford’s (1991) book In the Era of Human Capital: The Emergence of Talent, Intelligence, and Knowledge as the Worldwide Economic Force and What It Means to Managers and Investors” published by Harper Business, was a pointer to the kind of human capital that would be needed in the 21st century: unfragmented brains, in fragmented minds. That was the human capital in Galileo Galilei, which his university sought to suppress. Many such minds are being suppressed in our schools and universities, which are increasingly being restructured to preserve commitment to fragmentation of knowledge.

At the end if this discourse you will find many useful readings, which we think will help you to catch up with the age of wholeness and the rising importance of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary knowledge discourses in many Universities across the globe.

Fighting meaningfully and effectively for human rights, democracy, good governance, equity, justice, environmental conservation and against dictatorship, requires wholeness of minds and brains to see beyond hierarchies and barriers. Escaping from imprisonment of brain and mind by institutionalisation heavily buried in medieval times of European education, should be the way forward. An open, active society can take it as its duty, obligation and responsibility to demand this escape.

If not, then we forget all about fitting in the 21st century of wholeness under globalisation culture. It is absolutely important that universities are liberated from their debilitating conspiracy of silence imposed by interdisciplinary knowledge production and management. They will continue to be roadblock to mind liberation if they don’t become interdisciplinary and interdisciplinary, and their products will remain alien to the worldwide struggle to build an open society.

Bureaucratic knowledge production of intradisciplinarity will only continue to preserve bureaucracy or red tape in universities and societies and populate the globe with arrogant, ignorant, self-interested individual who take bureaucracy and hierarchy as both virtues and values to society.

As Bob Buckman, cited by Peters (1993: 426) says:

“Our (humanity’s) strategic advantage lies with the leverage of knowledge….The knowledge that each of us acquires will have a different meaning to each of us and will have a different meaning to those to whom we transmit it. The more steps in the process the more the knowledge changes and the more stale it becomes…new approaches to ‘knowledge processing’ are profoundly anti-bureaucratic…The most powerful individuals in the anti-bureaucratic future….will be those who do the best job of transferring knowledge to others”.

Therefore, educating to go beyond, beyond hierarchies should be the way forward for our higher learning centres. For us as individuals in higher learning centres we need to expose ourselves to the market’s craze for new knowledge production (e.g., Gibbons, et.al. (2007).

According to Gibbons, et.al. (2007), with new knowledge production, the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies are changing. On the other hand, Peters (1992) tells us not to ignore cyberspace corporations, which will be very fast-acting, transient and composed of bright. Creative, high-tech nomads who will coalesce into work units for dynamic market opportunities. Personnel turnovers will be high as tasks are completed and cyberspace workers decide to migrate to other opportunities. A very productive informal network will form as cyberspace workers leverage their rich set of experiences and contacts (Peters, 1992: 438). That is the science and work place environment of the shift to a knowledge-based society has ushered in. The terms cyberspace and corporate virtual workplace are now common place in the world of new knowledge production but still largely alien to the world of intradisciplinary knowledge production and workplace. Hakken (2003) addressed the knowledge landscape of cyberspace. Even if we looked back to the future, there is no real going back. We must get out of our cocoons and move on.

We must be ready to disorganise our predominantly intradisciplinary knowledge base in order to reorganise ourselves for the knowledge-based society increasingly getting dominated by new knowledge production and new knowledge workers, less stupid, less ignorant and less arrogant, and ready to learn anew.

Makerere University’s attitude towards new knowledge production

Makerere University was the first institution of higher learning south of the Sahara Desert, perhaps throughout Africa, to welcome the idea of New Knowledge Production. In 1996, with support from the University of Florida in the USA, the Human Rights and Peace Centre (HuRIPEC), based in the then Faculty (now School) organised the First Workshop on Interdisciplinarity, under the theme The Interdisciplinary Teaching of Human Rights, Peace and Ethics in Makerere University (e.g., Oweyegha-Afunaduula and Wingston, 1996). This workshop was the precursor for a six-year crosscutting project called “Interdisciplinary Teaching of Human Rights, Peace and Ethics at Makerere University (ITHPEP), which was based in the Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC) in the Faculty of Law and funded by the Ford Foundation.

However, initially, the University of Florida and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) were involved in the project and organised, together with Makerere University, the Second Workshop on Interdisciplinarity, intended to acquaint the administrators of the University with the Project aims and purposes (Oweyegha-Afunaduula and Asiimwe, 1998). Both the University of Florida and AAAS withdrew from ITHPEP early. Although I was a member of the board of ITHPEP and its vice-chairman initially, I never came to know why the two withdrew. One theory is that they did not see why they should continue since Ford Foundation had strongly come in to fund the project. Another theory was that the two institutions privately interacted with the university administration and some members of staff across the university curriculum and discovered there was inadequate support for the project.

According to this theory most administrators and academic staff saw the project as potentially disruptive, which would end up disorganising the strongly entrenched disciplinary culture of the university. Indeed by the time the project came to an end, the university had come up with new academic policy guidelines re-emphasising Intradisciplinary academic knowledge production. The new academic policy instrument more or less declared the new knowledge production pathway of interdisciplinarity, and by extension, transdisciplinarity, inferior to intradisciplinary knowledge production.

Called the Mujaju Academic Policy Guidelines, the policy hinged upward academic mobility on producing knowledge and in a discipline. Any knowledge production outside disciplines would not earn a knowledge producer and worker recognition in terms of promotion. I wrote a critique on the policy (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2004) and pointed out that the timing of the policy was intended to sway the wind of change towards interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary studies, back to confinement in disciplinary cocoons, with far-reaching human rights, ethical and academic consequences on the freedom of the academic staff to interact and associate more broadly outside their confinement in the disciplines.

I reasoned that academic staff would be denied the opportunities that would have been available to them at the intersections of disciplines. I suggested that with new knowledge production, it should be practicable for a team of knowledge workers to conceive a problem together, theorise together, research together, interpreted results together, write a thesis together, present the thesis together as a collective effort, defend it together and earn academic recognition together.

Before the Mujaju instrument sabotaged the growth in stature of the Interdisciplinary current in Makerere University, ITHPEP had been able to cause interaction between academic and administrative staff from different faculties, departments and discipline through several Interdisciplinary workshops and an international Interdisciplinary workshop (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. 2002). Several knowledge products edited by myself as chief editor had been produced. Most were on the challenges of curriculum integration in different faculties of the university (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. and B.G. Wairama, 2001).

A Makerere University Deans and Directors Task Force on Interdisciplinary Education had been established and came up with “Proposal for the Adoption and Implementation of Teaching of Interdisciplinarity Courses at Makerere University (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2004). Later, ITHPEP proposed Makerere University Comprehensive Policy on Interdisciplinary Education and Research (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2005). It was presented to deans and directors of the university, who then forwarded it to the university senate for approval and onward transmission to university council for approval of policy on interdisciplinary education and research in the university. The rest is history.

Therefore, although 47 years ago Janstch (1972) called for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary universities as a systems approach to education, Makerere University threw away the opportunity to be the leading university in Africa in that direction. There is no doubt that today new leaders in higher education are in the new knowledge production.

Apparently, Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), which established an Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies around the time Makerere University was resisting change, and now has an Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies, is the only leader in this arena in Africa today. Makerere University, by virtue of its policy design re-entrenching disciplinary knowledge production, acquisition and transmission, decided to be 47 years behind the wave of great interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinary universities of the world. It remains the “Harvard” of Africa in intradisciplinary knowledge production, but the Harvard of USA has moved on. Its scholars are among the leading knowledge producers in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinarity and its printing press has published numerous books and papers in academic journals on interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity.

Choosing interdisciplinarity in the 21st Century cannot be a virtue or value addition to the current knowledge base, which is increasingly crossdisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary. If we choose that path it means that if we want human resources the Century of information and knowledge, we shall not get them from Makerere University or any other University for which Makerere University has been, and continues to be, the role model.

I should not end this article without mentioning that our new centre, the Centre of Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA), under whose auspices this article has been written, was established to promote interaction between knowledge workers and producers committed to interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary knowledge discourses and/or imagination. In a way, it is an alternative university. It is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary centre of the type Jantsch (1972) envisaged for the 21st century.

It is open to knowledge workers and producers in and outside universities no longer motivated by intradisciplinary knowledge discourses, and who are ready to work, network and team up in new ways. The challenge is to address complexity (e.g., Holland, 2014; Young, 2017) and the big problems (e.g. Ledford, 2015) or what Brown, et.al. (2014) have called the wicked problems, which oversimplification has denied humanity to confront, through transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary imagination.

With this kind of imagination critical thinking and analysis become necessary allies in addressing human and world’s problems beyond regulation and inhibition by intradisciplinary thought frameworks towards innovative strategies for governing large complex systems (see also Young, 2017).

Concluding remarks

Let me conclude this article with advice from Tom Peters (1992) when he says:

“…Whether you are 25 or 55 you will always need to worry about where your career is going from today. As you think about your career, here are some questions to ponder:

- In what way are you personally more valuable on the marketplace than last year?

- What are your plans to make yourself more valuable in the marketplace than in the past?

- What specific new skills do you plan to acquire or enhance in the next year?

- What’s your personal strategic plan for your career over, say, the next three years?

- What, precisely, is it that you want to be famous for?

Let me add that in our increasingly globalised marketplace of ideas and practice enhancing disciplinary careers is unlikely to give individuals secure careers. However, embracing the new knowledge production via interdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity and nondisciplinarity should be the way forward for disorganising knowledge bases to reorganise for the 21st century of integration. Preoccupying institutions with the loosely integrating multidisciplinarity, which is glorified disciplinarity or interdisciplinarity, preserves fragmentation of knowledge, undermines integration of knowledge and does not prepare knowledge workers for the century of interconnectivity, integration and networks, or for new careers in the 21stCentury. That globalised Cultural Change in Knowledge Production ( e.g., Harvey, 2004) is on is not fiction. Continued resistance to the change is self-destruction in the long term.

Finally, recreating integrated knowledge (Rapport, 2000) is the way out of the trap of knowledge acquisition and knowledge transmission to the now open arena of creativity and innovation. It demands a rethinking of science in the age of uncertainty (e.g., Nowotny, et.al., 2001). With integration of knowledge, the myth of purity of knowledge is and should be a thing of the past. Besides, quality is not to be sought in enclosures called disciplines. As Robert Pirsig, cited by Peters (1992), says, quality is a direct experience independent of and prior to intellectual abstractions.

Intellectual abstractions of and in the disciplines, are therefore, not the creators of quality of knowledge. They are creators of men and women of small knowledges, ignorance and arrogance that are alien to the age of new knowledge production. We should have prepared our universities and ourselves for an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary future long ago. The new knowledge cultures of interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity are here to stay and will dominate knowledge structure and processes well into the future.

The more we resist accepting that this is the new knowledge reality and that we are late, the more we make ourselves aliens to the 21st century – the century of new knowledge production, new interactions and new networks not evident in the long-staying age of disintegration and fragmentation that started in the medieval times in Europe and invaded other academic and intellectual spaces, including our own.

Rejoinder

Mahir Balunywa, at the Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA) argues that University education is not for dogmatic brains, but is for open-minded, independent minded and critical thinking people; people who think openly with their minds, and brains while question everything that there is in the body of knowledge. He says, “Once man begins to follow without question, it means that man has reached the end of his thinking capacity. This is what we call etc-end of thinking capacity. It is for the same reason that academic institutions have put an age limit beyond which professors should stop teaching or influencing ideological construction in the home of academia.”

For the case of Makerere University, once a professor makes 75 years he becomes professor emeritus, meaning he can no longer contribute to knowledge creation. We, therefore, need to appreciate the vitality of intellectual knowledge innovation, not knowledge rigidities. Keeping on citing and recycling old knowledge does not make us credible knowledge workers and producers but knowledge conservatives and thus knowledge conservers. However, conserving knowledge is not and should not be the way forward, but knowledge innovation through research is the way to go. To effectively do this, we need to appreciate the foundation of knowledge (Thesis), but we also need to question the old knowledge (Anti-thesis) in order for us to come up with new ideas(synthesis). This is the spirit behind the notion of the Law of negation of the negation.

Knowledge can only be called knowledge if it is subjected to critical thought and critical analysis. Any body of knowledge without critical thought and critical analysis becomes expired knowledge and, thus, not healthy for human consumption.

Before we transmit knowledge we must make sure that such knowledge has been subjected to intellectual criticisms and found fit for human consumption. We need creativity and innovations in knowledge creation. This will lead us into innovating university students who can be Use-Full to our society. Use-Less university graduates have proved to be liabilities to our society.

Let’s, therefore, put emphasis on Use-Full knowledge dissemination, not on Use-Less knowledge acquisition. This way we shall be able to construct Hope-Full graduates, and get rid of Hope-Less graduates. Out of the Hope-Full graduates, we shall be able to have futuristic innovative and creative professors; not those who keep on citing the likes of Plato and Aristotle without any anti-thesis. This is not easily tenable in a society, which has over the centuries been constructed on dogmatic thoughts. It is a process, which must or has to begin with a class of courageous, curious, independent-minded, critical and open-minded people. To those who would wish to be part of this process, they need to appreciate the pangs that Galileo went through to get his point accepted. They should be ready to pay a price similar to or bigger than what Galileo paid to salvage knowledge.

Conclusion

Universities should be centres of innovation and creativity, not centres of dogmatic reasoning. Transmitting old knowledge into new generations won’t improve academic and intellectual societies at the higher institutions of learning. Does this explain why we have proud unemployed graduates? Does this partly explain why world economies are stuck with graduates who cannot think, act and decide rationally? Certainly yes. What is the way forward then? How do we get out of this intellectual crisis? We need to build a new class of intellectuals who can think, act interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary and nondisciplinary.

We need to get rid of the walls of disciplinary studies, for such studies affect our thinking through unnecessary boundaries of knowledge. Universities and governments should create an environment of open critical thinking. The current university professors should stop punishing their students for thinking outside the box. They should accept criticisms without punishment. That is when we shall be able to create the Galileo Galileis of this world for the 21st century.

I wish to add that creating a Galileo, one must walk the path of being isolated today, subjected to all sorts of intellectual insults and torture and having to be stupidified. This is what Galileo went through.

A comprehensive bibliography for knowledge reintegration

Ackoff, H.R. (1974). Redesigning the Future. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Allen. B. (2004). Knowledge and Civilisation. Boulder CO: West view Press.

Augsburg, T. (2014). Becoming Transdisciplinary: The Emergence of the Transdisciplinary Individual. World Futures, 70(3-4): 233-247.

Ayer, A.J. (1950). Language, Truth and Logic. London: Collancz Publishers.

Bammer G. (2013). Disciplining Interdisciplinarity: Integration and Implementation Sciences for Researching Complex Real World Problems. ANU E: Canberra, Australia.

Barry, A., et.al. (2008). Logic of Interdisciplinarity. Economy and Society, 37(2008): 20-49.

Bax Mansilla, V. et.al. (2006). Quality Assessment of Interdisciplinary Research and Education. Research Evaluation, 25: 69-74.

Bergmann, M., et.al. (2012). Methods for Transdisciplinary Research: A Primer for Practice. Frankfurt, Germany: Campus.

Bernstein, J.H. (2014). Displinarity and Transdisciplinarity in the Study of knowledge. Informing Science. 17: 241-273

Bernstein, J.H. (2015). Transdisciplinarity: A Review of the Origins, Development and Current Issues. Journal of Research Practice, Volume 11(1): Article R1, 2015.

Bery, I.A. and B.M. Bass (?). Conformity and Deviation. New York: Harper.

Bozerman, B. And P..C. Boardman (2003). Managing the New Multipurpose, Multidiscipline University Research Centres: Institutional Innovation in the Academic Community. IBM Centre for the Business of Government, Arlington, VA (2003): 55.

Brandt, P., et.al. 2013). A Review of Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science. Ecological Economics, 92: 1-15.

Brewer, G.D. (1999). The Challenges of Interdisciplinarity. In: Policy Sciences, 32(1999): 327-337.

Brier, S. (2009). Why Information is not Enough. Toronto, Canada: Toronto University Press.

Bromham, et.al. (2016). Interdisciplinary Research Has Consistently Lower Funding Success. Nature (30 June, 2016): 534: 684-687.

Brown, V.A., et.al.(Ed)(2010). Tackling Wicked Problems Through Transdisciplinary Imagination. Abington, Oxon, UK: Earthscan.

Burger, P. and R. Kamber (2003). Cognitive Integration in Transdisciplinary Science: Knowledge as A Key Notion. In: Issues integrative Studies, 21: 43-73.

Campbell, D.T. (1969). Ethnocentrisms of Disciplines and the Fishdcale Model of Omniscience. p. 328-348. Chicago: Aldine.

Cardonna, J.L. (2014). Sustainability: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carew, A.L and F. Wickson ( 2010). The T.O. Wheel: A Heuristic to Shape, Support and Evaluate Transdisciplinary Research. Futures, 42(2010): 1146-1155.

Castan, B. V. et.al. (2002). Practicing Interdisciplinarity in the Interplay Between Disciplines: Experiences of Established Researchers. Environmental Science and Policy, 12(7): 922-934.

Carson R. (1962). Silent Spring. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin

Choi, B.C.K. and A.W.P. Pak (2006). Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in Health Research, Services, Education and Policy: Definitions, Objectives and Evidence of Effectiveness. In: Clinical Investigative Medicine, 29(2006),: 351-364.

Clark, B. and C. Button (2011). Sustainability Transdisciplinary Education Model: Interface of Arts, Science and Community. In: International Journal of Sustainability in Education, 12(2): 41-54.

Collier, P. (1998). Complexity in Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems. London: Routledge.

Collins, R. W. (2008). Battleground: Environment. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Crawford, R. (1991). In the Era of Human Capital: The Emergence of Talent, Intelligence, and Knowledge as the World Economic Force and What it Means to Managers and Investors. New York: Hapetr Business.

Cromwell, A.L., et.al. (Eds)(3001). Looking Both Ways: Heritage and the Identity of the Alutiiq People. Fairbanks AK: University of Alaska Press.

De Freitas, L., et.al. (Eds). The Charter of Transdisciplinarity. Retrieved from the International Encyclopaedia of Religion and Science,http://inters.org/Freits-Morin-Nicolescu-Transdiscilinarity/

De Melli, M. (2008). Toward an All-Embracing Optimism in the Realm of being and doing. In: B. Nicolescu (Ed). Transdisciplinarity: Theory and Practice. p. 85-97. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Dressel, P.L. and D. Maras (1982). On Teaching SNC Learning in College. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Etzkowitz, H. and L. Leydesforff (2000). The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and Model 2′ to A Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations. Research Policy, 29 (2): 109-123.

Evan, T.L.(2015) Transdisciplinary Collaboration for Sustainably Education: Institutional and Intergroup challenges and Opportunities. Policy Futures in Education, 15(1)2015: 70-95.

Fahie. J.J. (1903). Galileo: His Life and Work. New York: James Pott and Company.

Feuer, L. (1969). The Conflict of Generations: The Character and Significance of Student Movements. New York: Basic.

Fisher, E. (2007). The Convergence of Nanotechnology, Politics and Ethics. Advances in Computers, 71: 273-296.

Florida, R. (2006). Minds on the Move. Newsweek, December, 2006.

Froderman, R., et.al. (Eds)(2010). The Oxford Handbook on Interdisciplinarity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, New York. p. xxix-xxxix.

Futures, Vol. 53 (September, 2013): 22-32. Preparing for an Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Future: A Perspective from Early Career Researchers.

Galileo Galilei, Dialogue Concerning Two New Science. Trans. From Italian and Latin by Henry Crew and Alfonso de Salveo. New York: Macmillan, 1994.

Garrett, E.M. (1990). One Thing Leads to Another. Folio’ Publishing News, August 15, 1990: 36.

Geertz, C. (1995). After the Fact. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Gibbons, M., et.al. (2007). The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London, UK: Sage.

Goring, S.J. et.al. (2014). Improving the Culture of Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Ecology by Expanding Measures of Success. Ecology and Environment, 12: 39-47.

Hakken, F. (2003). The Knowledge Landscape of Cyberspace. New York: Routledge.

Handy, C. (1989). The Age of Unreason. London: Business Books Limited.

Harris, R. (2009). After Epistemology. Gamlingay: Author Online.

Harvey, R. (2004). The Condition of Post-Modernity: An Inquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hessels, L.K. and H. Vonlente (2008). Rethinking New Knowledge Production: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Research Policy,37(2008): 740-760.

Hills, G. (1994). The Knowledge Disease. Resurgence, Vol 164 48.

Hirsch Hardin, G.H., et.al. (2006). Implications of transdisciplinarity to sustainability Research. Ecological Economics, 60: 119-128.

Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, Voice and, Loyalty. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Holland, J.H. (2014). Complexity: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hook, C.C.(2004). Nanotechnology. In: S. C. Post ( Ed). Encyclopaedia of Bioethics. p. 1871-1875. New York: MacMillan References USA.

Jantsch, E. 1972). Towards Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in Education band Innovation. In: Centre for education Research and Innovation. (CERI). Interdisciplinarity: Problems of Teaching and Research in Universities. p.97-101. Paris, France: OECD.

Jantsch, E. (1972). Interdisciplinarity and Transdisciplinarity in University: A Systems Approach to education and Innovation. Higher Education, 1(1): 7-37.

Karraker, R. (1991). Highways of the Mind. In: Sole Earth Review, Spring 1991: 4-6.

Keeney, R. (1992). Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision-Making. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Kessel, T. and P.L. Rosenfield (2008). Towards Transdisciplinary Research: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. In: American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(25): 5225-5234.

Klein, J.T. (1996). Crossing Boundaries: Knowledge, Disciplinarities and Interdisciplinarties. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Klein, J.T. (2001). The Discourse of Transdisciplinarity: An Expanding Global Field. In: Thompson Klein, et. al. (Eds). Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving Among Science, Technology and Society -An Effective Way of managing Complexity. p. 35-45. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser.

Klein, J.T. (2015). Reprint of “Discourse of Transdisciplinarity: Looking Back to The Future. Futures, 65: 10-16.

Klein, N. (2000). No Logo, No Place, No Jobs. New York: Picador.

Kockelmans, J.J. (1979). Why Interdisciplinarity? In: J.J. Kockelmans (Ed). Interdisciplinarity and Higher Education. p. 124-160. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Kumar, K. (1995). From Post-industrial to Postmodern: Society of the Contemporary World. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Lamb, C. (1990). Stimulating Creativities. In: Financial Times, March 20, 1990: 13.

Lands, G. (2006). Conclave in the Tower of Barbel: How Peers Review Interdisciplinary Research. Research Evaluation. 15: 57-68.

Lattuca, L.R. (2001). Creating Interdisciplinarity: Interdisciplinary Research and Teaching in College and University Faculty. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Lau, L. and M.W. Pasquini (2004). Meeting Ground: Perceiving and Defining Interdisciplinarity Across the arts Social Sciences and Sciences. Interdisciplinary Sciences, Reviews, 29(2006): 49-69

Lawrence, A.J. (2010). Beyond Disciplinary Confinement to Imaginative Transdisciplinarity. In: V.A. Brown, et.al (Eds). Tackling Wicked Problems Through the Transdisciplinarity Imagination. p. 18-30. Abington, Oxon: Earthscan.

Lawrence, R.J. and C. Despres (2004). Futures of Transdisciplinarity. Futures, 36(4):397-406.

Leavy, P. (2011). Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research: Using Problem-centred Methodologies. Walnut Creeks CA: Left Candt.

Ledford, H. (2015). How to Solve the World’s Biggest Problems. Nature, 525: 308-313.

Lyall, C. and L.S. Meagher (2012). A Master Class in Interdisciplinarity: Research into Practice for the Next Generation of Interdisciplinary Researchers. 44(2012): 179-194.

MacCancey, J. (Ed)(2002). Exotic No More: Anthropology of the Front Lines. Chicago IL: Chicago University Press.

Madna, A.M. (2007). Transdisciplinarity: Reaching Beyond Disciplines to Find Connections. Journal of Integrated Design and Process Science, 11(1): 1-11.

Magala, S.J. (1997). The Making and Unmaking of Sense. In: Organisational Studies, 18(2): 317-338.

Max Neef, M.S. (2005). Foundations of Transdisciplinarity. In: Ecological Economics, 53:5-16.

McGregor, S.L.T. (2015a). Integral Dispositions and Transdisciplinarity Knowledge Creation. Integral Leadership Review, 15(1). Retrieved from http://integralleadershipreview.com/12458-115-integral-dispositions-transdisciplinary-knowledge-creation/

McGregor, S.LT. (2015b). The Nicolescuian and Zurich Approaches to Transdisciplinarity. Integral Leadership Review, 15(1). Retrieved from http://integralleadershipreview.com/13135-616-the-nicolescuian-and-zurich-approaches-to-transdisciplinarity/

Messer-Davison, E., et.al. (1993). Knowledge: Historical and Critical Studies in Disciplinarities, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Mittelstrass,, J. (2011). On Transdisciplinarity. Frames, 15(4): 329-338.

Mooney, R. and T. Razk (1967). Explorations in Creativity. New York. .

Montuori, A. (2008). Forward: Transdisciplinarity. In: B. Nicolescu (Ed). Transdisciplinarity: Theory and Practice. p. ix-xvii.Cresskill: Hampton.

Nicolescu, B. (2002). Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity (K.C. Voss Transl.). Albany, New York: StatecUniversity of New York Press.

Nicolescu, B. (2008). In vitro and in vivo Knowledge: Methodology of Transdisciplinarity. In B. Nicolescu (Ed). Transdisciplinarity: Theory and Practice.p.1-21. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton

Nicolescu, B. (2010). Methodologies of Transdisciplinarity: Levels of Reality, Logic of the included Middle and Complexity. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering and Science, 1: 17-32.

Nicolescu, B. (2012). Transdisciplinarity: The Hidden Third Between the Subject and the Object. In: Had man and Social Studies, 1(2): 13-28.

Nowotny, H, et.al. (2001). Rethinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in am Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Nowotny, H., et.al. (2003). Mode 2′ Revisited: The New Know ledge Production. In: Minerva 41(2003): 179-194.

O’Dell, C. and C. Hubert (2011). The New Edge of Knowledge: How Knowledge Management is Changing the Way We Do Business. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. (2004). Interdisciplinarity: The Sense and Nonsense of Academic Specialisation. In: Ruth Mukama and Murindwa-Rutanga (Eds). Confronting Twenty-First Century Challenges: Analyses and Dedications by National and International Social Scientists. Vol. 1. Published by the Faculty of Social Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. (2004). Decision-Making in Makerere University: Human Rights, Ethical and Academic Implications of The Mujaju Policy Instrument: s Critique. Studying Human Rights, Peace and Ethics Through Interdisciplinary Lenses. SHRE-TIL-ITHPEP/1/ 2004, January. 17pp.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. (Ed)(2005). Makerere University Comprehensive Policy on Interdisciplinary Education and Research. ITHPEP/Makerere University Senate, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda (Prepared for Submission to Makerere University Council for Approval of Policy).

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. (Ed)(2004). Makerere University Deans and Directors Task Force on Interdisciplinary Education: Proposal for Adoption and Implementation of Teaching of Interdisciplinarity Courses at Makerere University. In: Task Force Report of Deans and Directors on Interdisciplinary Education Presented to the Academic Registrar, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. 2004.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F. C. and D. Asiimwe (1998). Report of the Proceedings of Makerere University Administrators Workshop on The Interdisciplinary Teaching of Human Rights, Peace and Ethics at Makerere University. Kampala, Uganda: Makerere University, Huripec/AAAS, Imperial Botanical Hotel, Entebbe, Uganda. 50pp. New York Public Library.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. and B.G. Wairama (Eds)(2001). Workshop Report on Interdisciplinarity: The Challenges of Curriculum Integration in the Social Sciences and Humanities. ITHPEP/HURIPEC/Faculty of Law/Makerere University. Rider Hotel, Seeta, Mukono, Uganda, 18-20 September, 2001. ITHPEP Resource Series No. 4. 60pp.

Oweyegha-Afunaduula, F.C. and D. Wingston (1996). Development (Environment/Ecology) and Human Rights. p. 45-48. In: Proceedings of the First Interdisciplinary Workshop on Human Rights Organised by HURIPEC/Faculty of Law, Makerere University, at Faculty of Agriculture, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, 1-8, August 1996.

Pedureen, A and C.T. Cheveresan (2010).Transdisciplinarity in Education. In: Journal Plus Education, 6(1):127-133.

Phenix, P. H. (1964). Realms of Meaning: A Philosophy of the Curriculum of General Education. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Polanyi, M. (1952). Personal Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Raoer, T. (994). The Pursuit of WOW. London: Macmillan.

Rapport, D.J. (Ed)(2000). Transdisciplinarity: Recreating Integrated Knowledge. Oxford: EOLSS.

Robinson, J. (2008). Being Undisciplined: Transgressions and Intersections in academia and Beyond. Futures, 40(2008): 70-86.

Selye, H. (1964). From Dream to Discovery: On Becoming a Scientist. New York: McGraw.

Taichi Sakaiya (1991). The Knowledge-Value Revolution. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Thompson-Klein, J. et.al. (2001). Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem-Solving Among Science, Technology and Society -An Effective Way for Managing Complexity. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser.

Transdisciplinarity in Higher Education for Sustainability: How Discourses are Approached in Engineering Education. Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 175: 29-37.

Vogl, A.J. (1991). Breaking with Bureaucracy. In: Across The Board, January-February, 1991:18.

Waldrop, M. (1992). Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. Simon & Simon: New York.

Weick, K.E (1996). Speaking to Practice: The Scholarship of Integration. Journal of Management Inquiry, 5: 251-258.

Dickson, F., et.al. (2006). Transdisciplinary Research: Characteristics, Quandaries and Quality. Futures, 38(2006): 1046-1059.

Wilson, E.O. (1999). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge: New York: Academic Press.

Woelert, P. and Miller (2013). The Paradox of Australian Research Governance. Higher Education, 66: 775-767.

Wolpert, L. (1992). The Unnatural Nature of science. Faber & Faber: London.

Young, O.R. (2017). Beyond regulation: Innovative Strategies for Governing Large Complex Systems. Sustainability, 9: 938. Google Book CrossRef.

- A Tell report / By F.C. Oweyegha-Afunaduula & Mahir Balunywa, Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis, Kampala, Uganda