It has been a difficult month for two Covid-19 vaccines. On April 13, US regulators urged healthcare providers to temporarily stop using a vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson (J&J) of New Brunswick, New Jersey, because of six suspected cases of unusual blood clotting among nearly seven million vaccine recipients.

The move came after European regulators expressed concerns about a possible link between rare blood clots and the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, developed in the United Kingdom by AstraZeneca in Cambridge and the University of Oxford.

Both decisions are having a global impact. Although researchers and regulators stress that the benefits of the vaccines outweigh the risks, several countries are restricting the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine to certain age groups and Denmark has opted out of using it altogether. J&J, meanwhile, has paused distribution of its vaccine to some countries.

“The way that it’s happened has just made us all feel that the world is a bit crazy,” says Susan Goldstein, a public-health specialist and deputy director of the SAMRC Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science in Johannesburg, South Africa. “There’s been a huge amount of confusion.”

Some of that confusion stems from an urgent need to act quickly on the basis of messy, incomplete and capricious real-world data. As regulators are forced to make decisions, scientists are still racing to investigate the rare clotting disorder and its link to the vaccines.

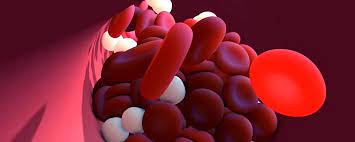

The clots that have been tentatively linked to the AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines have particular characteristics: they occur in unusual parts of the body, such as the brain or abdomen, and are coupled with low levels of platelets, cell fragments that aid blood coagulation.

Further analysis found other hallmarks of a condition called heparin-induced thrombocytopaenia (HIT), a rare side effect sometimes seen in people who have taken the anti-coagulant heparin1,2,3 — even though the vaccine recipients had not taken that drug.

HIT is thought to be triggered when heparin binds to a protein called platelet factor 4. This kicks off an immune response – including the production of antibodies against platelet factor 4 – that ultimately results in platelet destruction and the release of clot-promoting material. The mystery is what serves as the trigger for this syndrome in the absence of heparin.

The vaccines produced by AstraZeneca and J&J both rely on adenoviruses, which carry the DNA encoding a coronavirus protein called spike into human cells. The cells’ protein machinery then uses the DNA to make the spike protein, and the body develops an immune response against it.

At present, researchers don’t know what component of these vaccines could be causing the unwanted immune response against platelet factor 4. “It could be caused by the vectors, it could be caused by the spike protein, it could be caused by a contaminant present in the vector,” says viral immunologist Hildegund Ertl at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines rely on different adenoviruses, but the appearance of the HIT-like symptoms among recipients of both vaccines – and the apparent lack of a HIT-like response among recipients of a different type of vaccine, based on mRNA – has raised concerns that the problem could be common to vaccines that rely on adenoviruses. Another such vaccine is Sputnik V, developed by the Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology in Moscow.

In a press release, Gamaleya distanced Sputnik V from the other adenoviral Covid-19 vaccines. “All vaccines based on adenoviral vector platform are different and not directly comparable,” it said, pointing out that there are differences in the viruses used, the cells in which they were produced, the sequence of the spike DNA they carry, the methods used to purify them, and the dosage at which they are administered.

Virologist Eric van Gorp at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is co-chairing a consortium that will look at the effect of different vaccines on vascular cells grown in the laboratory. The group will also look for antibodies against platelet factor 4 in recipients of different Covid-19 vaccines.

The identification of a trigger will be important for future vaccines, he says. “Can we rely on adenovirus vaccines or will we need to rely more on mRNA vaccines?” he says. “That will be the key question for the near future.”

The ratio of risk to benefit is the most basic information that a regulator needs when deciding whether a medicine is safe, but this can be a difficult number to pin down.

- A Nature magazine report