A landmark study that endorsed a simple way to curb cheating is going to be retracted nearly a decade after a group of scientists found that it relied on faked data.

According to the 2012 paper, when people signed an honesty declaration at the beginning of a form, rather than the end, they were less likely to lie. A seemingly cheap and effective method to fight fraud, it was adopted by at least one insurance company, tested by government agencies around the world, and taught to corporate executives. It made a splash among academics, who cited it in their own research more than 400 times.

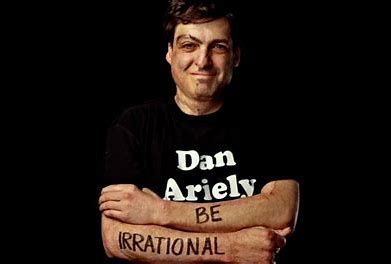

The paper also bolstered the reputations of two of its authors – Max Bazerman, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, and Dan Ariely, a psychologist and behavioural economist at Duke University – as leaders in the study of decision-making, irrationality and unethical behaviour.

Ariely, a frequent TED Talk speaker and a Wall Street Journal advice columnist, cited the study in lectures and in his New York Times bestseller The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves.

Years later, he and his co-authors found that follow-up experiments did not show the same reduction in dishonest behaviour. But more recently, a group of outside sleuths scrutinised the original paper’s underlying data and stumbled upon a bigger problem: One of its main experiments was faked “beyond any shadow of a doubt,” three academics wrote in a post on their blog, Data Colada, on Tuesday.

The researchers who published the study all agree that its data appear to be fraudulent and have requested that the journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, retract it. But it’s still unclear who made up the data or why – and four of the five authors said they played no part in collecting the data for the test in question.

That leaves Ariely, who confirmed that he alone was in touch with the insurance company that ran the test with its customers and provided him with the data. But he insisted that he was innocent, implying it was the company that was responsible.

“I can see why it is tempting to think that I had something to do with creating the data in a fraudulent way,” he told BuzzFeed News. “I can see why it would be tempting to jump to that conclusion, but I didn’t.”

He added, “If I knew that the data was fraudulent, I would have never posted it.”

But Ariely gave conflicting answers about the origins of the data file that was the basis for the analysis. Citing confidentiality agreements, he also declined to name the insurer that he partnered with. And he said that all his contacts at the insurer had left and that none of them remembered what happened, either.

According to correspondence reviewed by BuzzFeed News, Ariely has said that the company he partnered with was the Hartford, a car insurance company based in Hartford, Connecticut. Two people familiar with the study, who requested anonymity due to fear of retribution, confirmed that Ariely has referred to the Hartford as the research partner.

The Hartford did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Ariely also did not return a request for comment about the insurer.

The imploded finding is the latest blow to the buzzy field of behavioural economics. Several high-profile, supposedly science-backed strategies to subtly influence people’s psychology and decision-making have failed to hold up under scrutiny, spurring what’s been dubbed a “replication crisis.” But it’s rarer that data is faked altogether.

And this is not the first time questions have been raised about Ariely’s research in particular. In a famous 2008 study, he claimed that prompting people to recall the Ten Commandments before a test cuts down on cheating, but an outside team later failed to replicate the effect. An editor’s note was added to a 2004 study of his last month when other researchers raised concerns about statistical discrepancies, and Ariely did not have the original data to cross-check against.

And in 2010, Ariely told NPR that dentists often disagree on whether X-rays show a cavity, citing Delta Dental insurance as his source. He later walked back that claim when the company said it could not have shared that information with him because it did not collect it.

It is a failure of science that it took so long for the 2012 data to be revealed as fake, the scientists behind the Data Colada blog argued.

“Addressing the problem of scientific fraud should not be left to a few anonymous (and fed up and frightened) whistleblowers and some (fed up and frightened) bloggers to root out,” wrote Joe Simmons of the University of Pennsylvania, Leif Nelson of UC Berkeley and Uri Simonsohn of the Esade Business School in Spain.

Some are now questioning whether the scientist who literally wrote the book on dishonesty is himself being dishonest. But when asked whether he worries about his reputation, Ariely said he is not concerned.

“I think that science works over time and things fix themselves,” he said.

The 2012 paper reported on a series of experiments done both in a lab and in the field. In the main real-world experiment, the researchers teamed up with an unnamed car insurer in the US. Nearly 13,500 drivers were randomly sent one of two policy review forms to sign: one where the statement “I promise that the information I am providing is true” appeared as normal at the bottom of the document and the other where the statement was moved to the top.

People are naturally incentivised to lie on these forms, the scientists explained at the time, because a lower mileage means a lower risk of accidents and lower premiums.

Whether they signed next to the honesty pledge at the bottom or the top, customers were asked to report the current odometer mileage of their cars covered by the insurer. This number was compared to the mileage they’d reported over an unspecified time period in the past.

The researchers reported that the people who’d signed the top of the document reported driving more miles – about 2,400, or 10 per cent, more – than those who signed at the bottom.

While the actual mileage couldn’t be verified, the researchers hypothesised that this sizeable difference was due to the switch in signature locations. This easy tweak, they wrote, “likely reduced the extent to which customers falsified mileage information in their own financial self-interest at cost to the insurance company.”

The discovery fit neatly into a growing body of research about “nudging”: the idea that subtle cues can encourage people to unconsciously make the right decisions. The top-of-form signatures concept was tested on taxpayers in the United Kingdom and Guatemala, though to mixed results. A government in Canada also reportedly spent thousands trying to change its tax forms.

In the US, the Obama administration took notice, and the IRS credited the method with helping it collect an additional $1.6 million from government vendors in a quarter.

“Such tricks aren’t going to save us from the next big Ponzi scheme or doping athlete or thieving politician,” Ariely wrote in a 2012 Wall Street Journal excerpt from The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty. “But they could rein in the vast majority of people who cheat ‘just by a little.’”

“I think that science works over time and things fix themselves.”

Ariely went on to join the millennial-focused insurance start-up Lemonade as chief behavioural officer. His field “touches every aspect of our lives,” the company noted in 2016, including “cheating on our tax forms and insurance claims.”

Lemonade took a page straight out of the behavioural economist’s playbook: to submit fraud claims, customers must “sign their name to a digital pledge of honesty at the start of the claims process, rather than at the end,” Fast Company reported in 2017. (Ariely left at the end of 2020, according to his LinkedIn profile.)

- A Nature report