Editor’s note: The bouts of violence that have shaken Burundi since the 1960s received little attention compared to events in neighbouring Rwanda. So, when a truth and reconciliation commission began digging up mass graves to investigate atrocities, journalist Désiré Nimubona picked up his notebook. For more than a year, he travelled the country, following the commission and reflecting on Burundi’s troubled past – as well as his own.

A scar still runs down my right hand from when a schoolmate stabbed me in 1995 as I slept in a dormitory. He was a Tutsi whose brothers had been killed a few years earlier. In his grief, he blamed me, a Hutu. I owe my life to a blanket that was just thick enough to absorb that blade.

Yes, Burundi is a troubled place. The discovery of thousands of mass graves over the past year and a half makes that clear – especially in a tiny country of only a few million people.

The graves contain the victims of mass killings that have scarred my country for decades. As in neighbouring Rwanda, most died because of their ethnic background – either Hutu or Tutsi – though the killings here have received less attention.

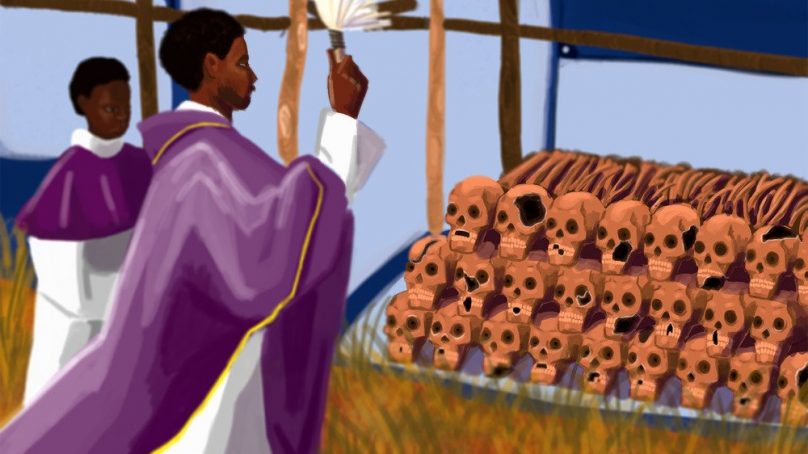

Now, gravediggers in jumpsuits and gumboots are picking through the remains, hoping to finally identify the dead and establish the circumstances in which these badly documented and poorly recognised genocide crimes took place.

The efforts are being led by a truth and reconciliation commission, like the one set up in South Africa after the end of apartheid. The idea for ours was conceived in 2000 as part of a peace deal brokered by Nelson Mandela, though it took a long time for work to commence.

Since January 2020, I’ve been following the commission, visiting graves and documenting atrocities around the country. I have seen some remarkable things: family members identifying the remains of their loved ones after decades of searching; killers asking victims for forgiveness.

But while the commission is shining some much-needed light on the past, old wounds are also being reopened. The process, some believe, is deepening divisions rather than helping us heal.

The commission is mandated to investigate atrocities dating from the 19th century, when Burundi was first colonised by a European power, to 2008, when the last active rebel group here signed a ceasefire with the government.

Critics say this timeframe ignores crimes committed since 2015. That was the year our deceased former president, Pierre Nkurunziza, won a controversial third term in office, triggering protests, a crackdown, and the displacement of some 400,000 Burundians.

Others say search teams are focusing on Hutu rather than Tutsi victims, particularly Hutus who died in a 1972 genocide. The commission denies being biased, but its close links to our ruling party – a former Hutu rebel group – mean some question its motives.

One thing is clear: We have all been affected by war. As the scholar of Burundi, René Lemarchand, once wrote: “Nowhere else in Africa have human rights been violated on a more massive scale, and with more brutal consistency, than in Burundi.”

That attempt on my life in 1995 was not my only brush with death. In 1996, Tutsi soldiers stopped me and my friends by the side of the road, claiming we were Hutu rebels. They made us lie down with two metres between us. An armoured truck then edged forward, crushing my friends to death, one by one.

I survived thanks to a local Tutsi man – François Mbesherubusa – who was passing by. He knew my father and told the soldiers: “Désiré is like my son; you must release him.” My friends Bigirimana, Yohani, and Gerard were not so lucky. Their deaths still haunt me after 25 years.

Mbesherubusa passed away some years ago, but my family has stayed in touch with his. After his death, I brought clothes to his wife as a gesture of my gratitude. And I work today alongside his daughter for a business cooperative that aims to combat rural poverty in southern Burundi.

Much has changed in recent years. A peace agreement in 2000 – and subsequent accords with rebel groups – helped establish a Hutu-Tutsi power-sharing arrangement that has eased ethnic conflict.

But so far there hasn’t been any real accountability, or any meaningful engagement with our country’s past – an oversight the Truth and Reconciliation Commission now seeks to correct.

Finally set up in 2014, the commission began a nationwide campaign of mapping and exhuming graves last year at a sensitive moment: New presidential polls were being held even as the Covid-19 pandemic wormed its way into the country.

I started shadowing the commission’s workers in Karuzi and Gitega, two provinces in central Burundi. It took me two and a half hours to drive to my first destination from Bujumbura, my hometown and the country’s largest city. The rain poured down on rolling hills.

Many people lost their lives in these provinces during the killings of 1972 – the worst Burundi has ever experienced. We call the events Ikiza, which means scourge or calamity in our local language, Kirundi.

Mainstream scholars say the conflict began when Hutus – the majority ethnic group here – launched an abortive uprising against the government, which was controlled by elites from the minority Tutsi population. Around 3,000 Tutsis were killed.

Led by an army officer called Michel Micombero, the government and the all-Tutsi military responded with inconceivable brutality, killing between 100,000-300,000 Hutus in what many consider a genocide.

I was born six years after the bloodshed, but it has shaped my life, as it has so many others. My parents named me Nimubona, which means “only God will protect him.” It was out of fear for my life if the carnage restarted.

- New Humanitarian report / Désiré Nimubona