In 1972, they blocked journalists who tried to investigate the killings, they prevented people from mourning the dead

Burundian reporter’s notebook: On his way to execution, a well-known Hutu priest and philosopher, kept chanting hymns saying ‘We are going to our father’s house’

I learned about what happened from my grandparents, who lost relatives and friends. I saw my first grave at the age of seven, when engineers unearthed remains while building a road that passed by my house. Among a jumble of bones was a rusty wristwatch that belonged to my father’s close friend, Aaron, who was arrested and disappeared in 1972.

Still, nothing prepared me for what I saw and heard last year when teams of gravediggers uncovered dozens of mass graves in central Burundi containing the bodies of thousands of people who had died in 1972.

The graves had been found on the banks of a river, beneath banana and avocado trees that commission experts think were planted to conceal the truth. I wondered whether local residents had eaten from them unknowingly.

Bones from different sites had been gathered from the pits and displayed in large piles in canopy tents. The scale was staggering, as were the stories from witnesses I interviewed to try to understand what had happened.

In Karuzi, I met Maximilien Barampama, a local man who was incarcerated at a prison in Gitega for petty theft when massacres began in the two provinces. Soldiers forced him to help carry out the killings. “I was used,” he told me. “And I obeyed to remain alive.”

Barampama explained that Hutus considered educated had been targeted. It was the same across the country: Businessmen and civil servants died in the thousands, alongside pastors, teachers, and students – some still at primary school.

In Gitega, the victims were brought to a local prison, where they slept in squalid cells with no bathrooms. Then they were loaded onto trucks and driven to deep pits dug by bulldozers.

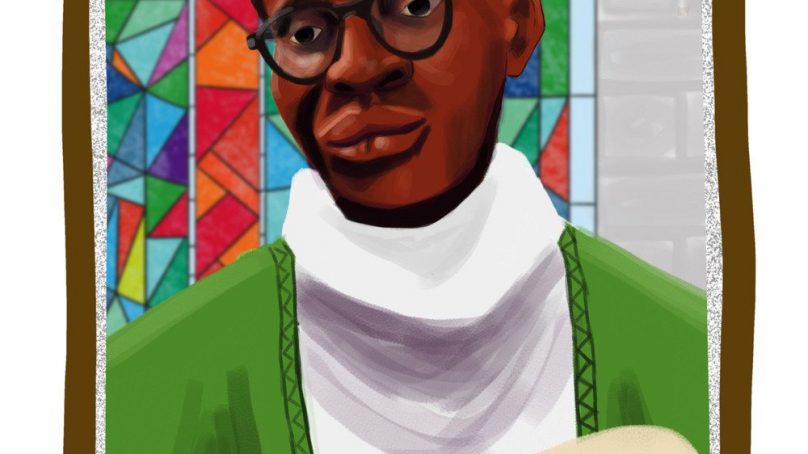

Among them was a well-known Hutu priest, writer and philosopher, Father Michel Kayoya. Despite atrocious conditions in prison, Barampama and others told me that Kayoya sang gospel songs and invited people to pray alongside him.

Even on his way to the execution site Kayoya kept praying and chanting hymns, Barampama told me. “We are going to father’s house,” he recalled the priest singing, over and over.

Before Kayoya was executed, the priest absolved the sins of his fellow clergymen and clergywomen, Barampama said and removed a stole he considered too holy to be buried. Soldiers shed tears even as they shot him dead.

During an exhumation in Gitega, glasses that looked like Kayoya’s were discovered, alongside rosary beads and other liturgical clothes. I watched as local residents and religious figures turned up to pay their respects.

The genocidaires’ focus on educated Hutus led scholars like Lemarchand to describe the events of 1972 as a “selective” or “partial” genocide: The goal was to create a Hutu underclass and solidify Tutsi control over a one-party state for decades to come.

The cruelty of that mission, which succeeded, had left its mark on Barampama: He was released from prison in 1973 when his sentence ended, but nearly five decades on the trauma was still etched on his face.

There is no longer war in Burundi, but problems persist. Poverty is widespread, land tensions are common, and rebel groups are still active across the border in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where everyone in this region tends to dump their problems.

Things have worsened since 2015: The space for civil society and independent media has shrunk, while international criticism has pushed the government into isolationism. Our new president, Évariste Ndayishimiye, has been praised for freeing journalists and renewing diplomatic ties in his first year in office, but there is much still to be done.

Our issues rarely get mentioned by foreign media, and our needs rarely get met by humanitarian groups. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council, an international aid organisation, Burundi is currently the third most neglected crisis in the world.

Our past is neglected too. Unlike the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in neighbouring Rwanda – a country whose history is interwoven with ours – the tragedy of 1972 played out with little attention at the time, and has got even less since.

It is what the government in 1972 always wanted: They blocked journalists who tried to investigate the killings, and they prevented people from mourning the dead in the years of state-enforced silence that followed.

Burundians I spoke with want more from the commission than simply chronicling the bloodshed, though: Most have lost family members during the killings and were hoping the exhumations would bring personal closure.

Every day, crowds would gather at the graves in the different places I visited, watching exhumations unfold behind crime scene tape, while commission workers interviewed those willing to talk.

To identify bodies, the search teams weren’t taking DNA samples: Instead, they held up belts, shoes, clothes, and other items pulled from the ground in the hope that residents would recognise who they belonged to.

Sometimes it worked. In Karuzi, I met Laetitia – she didn’t give her surname. She had followed an exhumation for 10 days, hoping to find her father. Finally, search teams pulled out black sandals and a skull with dental implants that identified him.

As per Burundian culture, confirming her father’s death meant a formal mourning ceremony could finally be arranged. “I feel sorrow for the death of my father, but joy at finally seeing his remains,” Laetitia told me as we cried together.

Rights groups have criticised the commission for failing to follow forensic standards, and for not storing remains in a dignified way. But the Burundians who comprise these search teams have their own powerful personal stories that highlight what’s at stake.

“I just want to be the first to see my grandfather’s remains.”

- The New Humanitarian report