In the northern province of Kirundo, I met the daughter of a Tutsi army corporal – Emmanuel Ndahigeze – killed for the crime of feeding Hutu prisoners. And in Makamba, Hutu residents told me about a Tutsi pastor who challenged soldiers carrying a list of Hutus to be killed in 1972.

“When he heard that there was a list, he searched for it,” Protais Ndayizeye, a local resident told me. “When he got it, he tore it into pieces, and some lives were saved like that.”

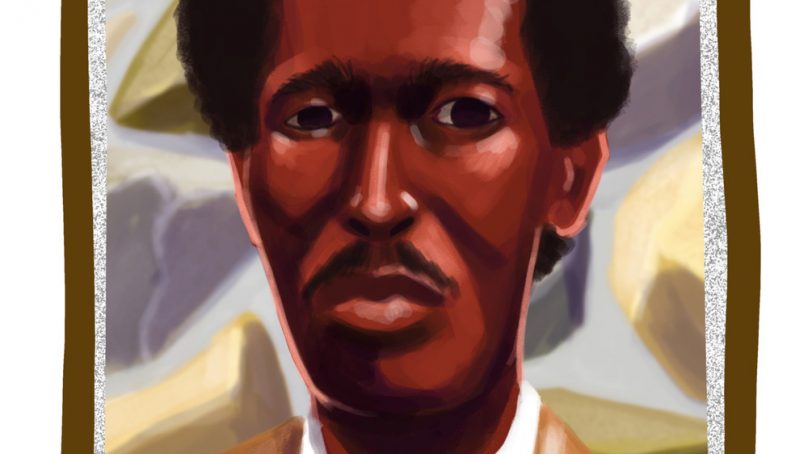

My father, Michael Nditunze, would have lost his life in 1972 if not for the courageous intervention of two Tutsi men – Cyriaque Ndenzako and Pascal Ndikumana – who had been his friends since childhood.

Father had a small business at the time selling clothes, food, blankets and palm oil in Nyanza Lac, a southern lakeside town. When 1972 came around, he found himself being hunted by gangs of Tutsi youth associated with the military.

Ndenzako, a soldier in the army – who feigned sickness to avoid participating in the killings – risked his life by sheltering father. Ndikumana – a well-respected local businessman – risked his by telling the youths that father had fled.

Our three families have remained close ever since. My sister is a godmother to Ndikumana’s daughter. And I have promised to help support the education of Ndikumana’s son, Havyarimana, and one of Ndenzako’s daughters too.

While my father – who is alive and well – owes his life to his friends, other Hutus in Makamba owe theirs to my courageous grandmother, Pétronie Ntirandekura, who died two years ago, aged 85.

In 1972, a group of soldiers drove into her village seeking out local Hutus. To stop the carnage, she walked to the end of a road leading out of the village and removed one of five tree trunks serving as a bridge over a small stream. The soldiers got stuck as they tried to leave, allowing the prisoners to escape via a nearby forest.

It is not clear what will happen when the commission finishes its investigations. Though mandated to establish responsibility for crimes, it is not a judicial body with power to prosecute. And though it may suggest reparations be paid to victims, resources here are limited.

By the time its work is completed, however, my hope is that the majority of Burundians will be satisfied with what has been uncovered, and will have some clarity on what happened to their loved ones.

Whether this happens under our current government remains to be seen, but we have to start somewhere. In the meantime, I believe all Burundians must do our bit to forgive each other.

In 2013, I had an opportunity to pursue personal reconciliation. I was working on a story for Radio Isanganiro – an independent station founded to support community reconciliation – about a charity providing legal aid to prisoners.

As I drove towards the entrance of the charity’s office in Bujumbura, a guard walked over to lift the security barrier. It took me a moment to realise who I was looking at: the man who had tried to stab me in my dormitory nearly two decades earlier.

As I left after the meeting, I greeted him and asked if he remembered who I was. At first, he said “no”; then, after a few moments, “yes”. He said he had a lot he wanted to tell me but that he was in a hurry. We shook hands and parted ways.

I heard nothing about the man until a year later when he arrived at my office in downtown Bujumbura unannounced. I wasn’t present, and he didn’t leave his number with the guard on duty.

Twelve months later, a new crisis broke out when our former president stood for a third presidential term. Gunfire and grenade blasts rocked Bujumbura. Some feared a repeat of the past and fled the country.

Last year, I posted on my secondary school WhatsApp group, asking for information about the man. Some people said he had moved to Rwanda; others suggested Uganda. Nobody seemed sure.

Wherever he is – and whatever happens next in Burundi – I hope he knows that my door is always open, and that he is already forgiven.

- The New Humanitarian report