As donors divert millions in development funding towards Eastern Europe, the South Asian country is edging closer towards what should be a preventable collapse, United Nations staff fear.

“If it turns into a humanitarian emergency, then there will be some attention and some funds, but we want to avoid that,” said UNICEF’s Sri Lanka representative, Christian Skoog.

Approximately $150,000 from Sweden, initially pledged to support child protection programmes in Sri Lanka, has already been reallocated to Ukraine instead, according to Skoog. “We need more funding now,” she said.

But the issue goes beyond funding. In the early days of the war in Ukraine, emergency responders were redeployed from all over the world to meet the crowds of exhausted refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion. The expertise such staff provided was critical, according to Jan Egeland, secretary general of Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

“[Ukraine] is a major emergency,” he said. “Tell me any place on Earth with 14 million people who were displaced in three months. There are no examples in recent history of the same thing happening.”

Even so, the massive movement of staff is proving problematic, with aid workers left behind in other parts of the world saying the absence of their colleagues – combined with rising costs and dwindling resources – has made them unable to operate at full capacity.

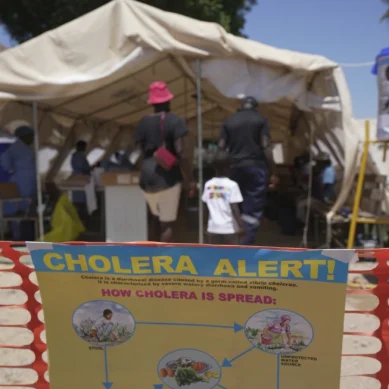

In Haiti, where political instability has seen poverty and gang violence reach dangerous heights, support on the ground is notably lacking. “Not only are our needs increasing, our ability to address the needs is decreasing,” Cara Buck, Mercy Corps’ country director in Port-au-Prince, said.

At least one senior-level colleague who had been set to work with Buck’s team has been reassigned to Ukraine instead. “It has tangible effects on what we’re trying to do here, because the resources and individuals that typically would be supporting us are no longer supporting us,” said Buck. “It’s extremely frustrating.”

With no signs of the situation in Ukraine improving in the near future, NGOs and UN agencies are expanding their footprint in Eastern Europe: opening dozens of offices in neighbouring countries, and advertising hundreds of roles for staff.

William Spindler, senior external engagement coordinator for the Americas for the UN’s refugee agency, says that, while UNHCR is yet to feel the full impact of funding cuts in the region, the reallocation of human resources is already taking a toll.

“The only thing that is really affecting our operations is the loss of experience to Ukraine,” Spindler said. “The people who we normally have on standby in case of emergencies have already gone.” Now, UNHCR is talking about redeploying additional staff from other operations in Latin America to Ukraine, he added.

“Personally, when I go into a nutritional centre and find a child less than five years old dying in front of my eyes because of lack of access to water or food, I’m not the same when I go into that centre as when I come out of it.”

Filling the roles in other parts of the world that so many aid workers have vacated so they can work on Ukraine is proving an additional challenge. “There are some examples of it becoming [more difficult] to find qualified people to go to hardship posts in more remote places, compared to Europe,” said Egeland. “That’s a concern.”

In the past four months, Maalim has seen an increasing number of staff members struggle with their mental health.

“Personally, when I go into a nutritional centre and find a child less than five years old dying in front of my eyes because of lack of access to water or food, I’m not the same when I go into that centre as when I come out of it,” he said. “Our current inability to assist people is having massive implications on our staff on the ground because they can’t support the people in need.”

It doesn’t help that, as inflation rises, staff salaries have also taken a hit. Local employees for NGOs based in Africa and Latin America complain that they and their colleagues are struggling to afford the fuel they need to get to work, while others expressed concern that if costs continue to surge, they won’t be able to afford to feed their own families.

One full-time staff member for an international organisation in the Democratic Republic of Congo said he is considering taking a second job in the evenings, otherwise he won’t be able to afford to pay rent. “It affects me psychologically,” he says, preferring to remain anonymous because he fears professional repercussions if his employer finds out he is planning to work two jobs. “You need money to survive,” he added.

Some organisations, such as Mercy Corps and NRC, have already begun the process of reviewing team members’ salaries to respond to the rapidly inflating cost of living. “Staff are really feeling the bite of price rises,” said Caitlin Brady, NRC’s country director in the DRC. “But probably we won’t be able to give them as much as they need – just because the situation here is so underfunded.”

For many, the conflict in Ukraine highlights pre-existing issues within the aid sector – exposing a world where attention spans are short, and funders are all-too fickle.

Last year, on Saturday August 14, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake struck Haiti’s westernmost peninsula, killing more than 2,200 and leaving half a million people in need of urgent support. Over the following 48 hours, Buck and her team at Mercy Corps gave more than a dozen media interviews in a bid to raise funds.

“But by Monday we knew that our window to advocate and increase visibility on Haiti was over,” she said. “After that, everyone moved on to Afghanistan.”

With the number of global disasters on the rise, experts say the humanitarian sector’s current approach to responding to crises is increasingly unsustainable – not to mention arguably dangerous.

“When you suddenly leave populations less protected, they’re more likely to fall into further conflict,” said Tjada D’Oyen McKenna, Mercy Corps’ CEO. “You just amplify the problems and create more situations of instability. And that’s exactly what we’re supposed to be fighting.”

Many senior aid workers and experts believe the solution lies in sector-wide reform, shifting the current model of rapid emergency response to one of crisis prevention, where programmes last long-term and resources are less at risk of being abruptly diverted or cut.

Oscar Gomez, associate professor of international relations and peace studies at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, supports this approach, but added that he would also like to see humanitarian actors pushing for more flexible contracts with public and private donors, enabling them to raise the full amount of funds they need for each crisis, while retaining the freedom to divert any excess elsewhere.

“Organisations could say, ‘You know, we don’t need more money for Ukraine, so any additional money that you give us, we might move to a different crisis because the need is there’,” said Gomez. “But this is something that organisations don’t want to do, because they don’t want to say no to money.”

Until major players show willingness to publicly admit when they’ve reached their funding targets for a certain region, Gomez fears a repeat of the situation that followed the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004. “You had all kinds of people out there doing stuff that didn’t make sense, just because they had the money and they needed to spend it,” he said.

Five thousand miles away from Kyiv, in the Horn of Africa, Khalif from Action Against Hunger is struggling to remain hopeful about when help will return to Somalia. With every day that passes, more children are dying. “It’s never getting better, and we’re not getting the resources that we need,” he said. “We’re doing as much as we can, but it’s not enough. We need food. We need water. We need money.”

- The New Humanitarian report