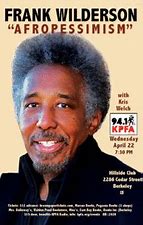

In Afropessimism, Frank B. Wilderson III – a snarky signifying furthermucker on the page – describes a moment of extreme annoyance after a film lecture he gave in which junior partner exceptionalism figured in his narrative analysis. A distraught white female academic beseeches him, “What about solidarity between races?” Wilderson’s now-infamous reply: “I don’t give a rat’s ass about solidarity.”

Shocking and enraging as that response might be to some – and hilarious and rallying to others – the fact is Wilderson, who teaches at UC Irvine and is in a long-term partnership with a white female poet, can’t actually escape solidarity with the junior partners.

There are, in fact, according to one prominent Black woman race theorist, Asian women in academia who now describe themselves as Afropessimists. Which speaks to the cool factor of AP as yet another example of Blackfolks’ ability to make any odd thing we touch – like Timberland boots and scratch DJ battles – seductive and hip to the non-Black junior partners.

James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.” But what he didn’t say was that, on a good day, it is mostly a sublimated state of rage since folk got bills to pay and sanity to keep. There are many successful Black women in the corporate world and in academe who are currently angry as f**k at having been hauled in to wet-nurse Diversity, Equity and Inclusion sessions by their employers – in addition to doing their 80-hour-a-week jobs. Since they don’t want to be identified as That Angry Black Woman, no one is the wiser in the hierarchy.

This may partly account for the current Afropessimism boom, in which Wilderson’s desublimation of his own rage into the highfalutin language of anti-racist structural analysis provides the sisters a safety valve and an intellectual alternative to depression or going all “Pirate Jenny” (see Nina Simone’s slave-revolt take on the Brecht-Weill ditty) on fools at their gig.

According to a couple of Black critical race feminist professors we know, there are undergraduate students who haven’t actually read Wilderson but have nonetheless adopted AP as their rallying cry after coming home from Black Lives Matter protests despairing that nothing they do “is going to stop these cops from killing us.”

For some, this despair leads to their own feelings of “Fuck solidarity” and a petulant, pissed-off urge to withdraw from interaction with white people – especially the staunchest of former allies – while they sort themselves out.

Nonacademic Black-folk from the grassroots activist side of the table sometimes ask: So what’s Wilderson’s “solution”? In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Wilderson lived in South Africa, where he was a mostly report-writing member of uMkhonto we Sizwe – the military wing of the African National Congress. He dedicates Afropessimism to “Assata Shakur and Winnie Mandela, for everything.”

So, it’s not a huge leap to guess his vision for making real change in the systemic anti-Black state of things is aligned with a version of theirs. But Wilderson has never positioned himself as a movement savant.

AP is not a political directive toward anything – other than Blackfolk not getting fooled again by the promises of solidarity from junior partners whose reality-construct is as dependent on the reproduction of Black suffering – upon not being the nigger – as the titular Humans (white boys by any other name).

Malcolm X once told a Black audience, “You sure don’t catch hell because you’re an American, because if you was an American, you wouldn’t catch no hell.” (Bettmann)

While Wilderson’s hardline on the place of Slaves, Humans and junior partners might lead you to believe Afropessimism is a full-throttle tract, the book is much more of a classic bildungsroman. Wilderson has led a dramatic life – and he is also an adroitly and acerbically self-dramatising furthermucker and an exquisite writer of modern, novelistic prose.

Among our key critical-race-theory guiding lights, he is hands down the one you read for pleasure, pathos, cringingly vulnerable interpersonal confessions – and sometimes even wrathful, biting comedy. The brother has a theatrical flair. And he doesn’t eschew self-deprecation on an operatic scale.

It’s hard to imagine, for example, another Black male writer who’s devoted himself so unsparingly to excavating scenes from his parents’ marriage – Spike Lee’s Crooklyn is the only work that resonates on similar frequencies – or detailing his multiple, tear-jerking inadequacies in nearly every romantic relationship of his teen and adult life (though not without much picaresque laughter as well).

The annoying and earnestly woke young Wilderson’s torture of his bewildered parents with his Soul on Ice-inspired ultra-Blackness sets up Afropessimism’s best one-liner. One 1960s pre-Nixon-impeachment day, young Frank, ever the adolescent scamp-provocateur, rolls up on his mother and blindsides her by proclaiming his newfound desire to fight in Vietnam.

Mom exhales, then professes pride in her renegade Marxist-wannabe spawn finally embracing the American way. At which point Wilderson launches his spring-loaded ambush: “You don’t understand me. I didn’t mean the White man’s army, I meant the Viet Cong!”

By contrast, some of the most moving and painful writing in Afropessimism occurs in the book’s conclusion, when the author recounts his deeply admiring final reflections and memories of his mother, before dementia renders her a complete stranger to him:

Then she asked me if I had just come from the Washington Monument. When I said no, we’re in Minneapolis, not in DC, she said I never did have a sense of direction, no wonder I’d come late for my sister’s recital.

“What recital,” I wanted to know, “where?”…

“What do you mean, where? The Jack and Jill convention, down the hall in the ballroom, silly.”… [S]he held up her index finger. “Listen. Your sister plays beautifully.”

The Jack and Jill convention must have been in 1970, and my sister had not played the piano for almost forty years. But I sat with Mom and listened to the end of the concerto, or was it an étude? Then came an ice age of silence in which she said nothing and seemed not to notice I was there. Snowplows groaned in the street below her window.

The branches of trees were bare and starred with frost. Where was the woman who danced slowly in her stocking feet with my father in the living room at night, Johnny Hartman on the hi-fi and not a worry in the world? The woman who said my stock was good and my mind was strong. Where was she, the woman who made me want to write?

Her hair was as white and thin as dandelion puffs…. She had not spoken for a while. Then, as if she’d been reading my mail, she sat up straight as a washboard…. Like Harriet Tubman staring down a gun barrel, she looked at me. “Didn’t I tell you, boy, people have to die? I know I told you that.”

I went into the hallway so she wouldn’t see me cry. When I returned to the room, she asked me who I was.

Earlier, after giving both still-very-lucid parents a full description of Afropessimism, Wilderson recalls his mom querying him as to what purpose something like that could have for his students, and whether it might help them become “good citizens.”

The mature, middle-aged Wilderson doesn’t claw back. But after you smirk at his mother’s seeming naivete, you’re left wondering if Ma Dukes didn’t just signify on her boy in that blithe and cunning way Black mothers can do so well: cutting their grown and tenured progeny’s vestigial outlaw illusions off at the neck so cleanly they never even felt the slice of the blade.

- The Nation report