We learn a lot from each other. So, in a way everyone qualifies to be a teacher of another. Indeed, teaching is a natural avenue that ensures that we remain interconnected and integrated mind-wise despite a long history of human effort in disconnecting minds via the creation of disciplines (or cocoons) of knowledge.

Even animals called predators teach their young ones how to hunt. Birds teach their young ones how to fly. Only snakes are stupid. They never teach their young ones anything, because they abandon them to the hazards of nature and to fend and hunt for themselves.

Otherwise, learning through being taught is a universal phenomenon. But learning may be experiential learning and, therefore, informal, unlimited to institutions such as schools and universities. It is the more common learning. More frequently than not, it involves interacting with the environment directly, observing and learning from interactions with it. In other words, the environment teaches us and we learn from it. In the 21st Century, the environment is increasingly dominated by the Worldwide Web or Internet, which is a source of much teaching and learning. One lives in the past if one is not being taught or learning from the virtual media.

Teaching and learning constitute education. And through education, whatever aims are targeted by the enterprise of education, we may or may not build communities and we may or may not usher in change. It is, of course, best that education builds communities and makes them cohesive through enhancing interconnectivity culturally, ecologically, biologically, socially, physically and mind-wise today and well in future.

It must be education for change as well, not backwards but forwards. If education can build communities for change and communities of change, then we cannot practically and collectively experience development, transformation and progress rather than as individuals, if we agree that individuals exist (in biology and ecology, individuals do not really exist).

Meaningful and effective education is for holistic change and experience. Unfortunately, this is not the case because education has been bracketed in numerous small pockets of knowledge with rigid walls through which cross-communication is impossible. So, whole human beings are difficult to teach and produce with capacity to grasp issues, problems and situations in their entirely and provide solutions that help to create and innovate.

infed.org defines teaching as “the process of attending to people’s needs, experiences and feelings, and intervening so that they learn particular things, and go beyond the given”. This definition allows for community education as well and for education outside schools, universities and other institutions.

Jesus Christ taught without any need for formal institutions. Any place was good enough for him to teach and impact people with the Word of God, although in some instances anti-Christs chased him away, preferring ignorance of the Word.

The ancient Greek philosophers (men of knowledge) such as Socrates, who taught long before the advent of Jesus Christ) did their knowledge work with no need to institutionalise it. The Socratic Method of teaching has remained influential to-date. Their teaching was effective in the sense that learners, and by extension society, benefitted immensely and passed the knowledge on to future generations. We still value the knowledge they generated and passed on, especially the critical thinking involved.

The infed.org definition seems to be a better definition than the one given by Wikipedia as “the practice implemented by a teacher aimed at transmitting skills (knowledge, know-how and interpersonal skills) to a learner, a student or any other audience the context of an educational institution”. The Wikipedia definition occludes education that occurs outside teaching that occurs outside schools, universities and other institutions. It seems to imply that education outside these institutions is non-education yet most education is outside these institutions.

By extension it embraces the view that teaching as a profession and training as a practice cannot occur outside the school, university or other institutions. So much teaching, learning and hence education, occurs outside institutions designated as educational institutions. For example, traditional or indigenous societies in Africa have since time immemorial produced and had its teachers producing professionals in medicine, art, music, dance, drama, pottery, etc.

It was colonialism that destroyed indigenous education and replaced it with school or university-based education. Nevertheless, there is still room for extra-school or extra-university education and for interaction between school and university education and indigenous knowledge systems. This is being exploited via the stakeholder teaching and learning enterprise that involves all across the board.

Modern-day interventions in education commonly take the form of questioning, listening, giving information, explaining some phenomenon, demonstrating a skill or process, testing understanding and capacity, and facilitating learning activities (such as note taking, discussion, assignment writing, simulations and practice). Even all this occurred in indigenous knowledge systems. What were absent were writing and taking note, since teaching and learning depended almost entirely on meeting of minds and practice in a well-knit fashion.

Starting mainly with the Modern Age in Europe, disciplining of knowledge, professionalising teaching and training have created the impression one is not a teacher unless one has attended a teacher training college or pursued education in a prescribed discipline of knowledge. With passage of time, there is a wrong belief that one cannot teach unless one has a degree, particularly in education. In Uganda, teachers who were already in service but had no degrees were given 10 years to upgrade their education to degree level or risk being dumped by the Ministry of Education.

They are remaining with six years to do so. The question, however, remains, does one need a degree to teach and teach well enough for learners to benefit and excel? Jesus stands out as the greatest of the greatest of teachers who never had a formal degree in what he taught.

Famous Italian scientist, Galileo Galilee made his discoveries, including the one that it was not the Sun that went round the Moon but the Moon that went round the Sun, when he had no formal degree. He was chased from his medical programme when he was in his first year of study because he questioned his professors’ way of teaching by reciting archaic writings of ancient philosophers, without any questioning He cut classes to do his private experiments in physics instead. He even became a Professor of Physics in a renowned University without a university degree and went on to supervise students to acquire their PhDs.

Michael Faraday, one of the greatest English scientists of the 19th Century who contributed immensely to our understanding of the science of electromagnetism, was a self-made scientist, but benefitted greatly by being a laboratory assistant to Sir Humphrey Davy. He did not have a formal degree in either physics or chemistry when he made his contributions. Many knowledge workers who became renowned scientists at universities in the Western World benefitted greatly from the non-degreed Faraday, the greatest discovery of Sir Humphrey Davy.

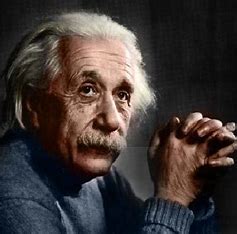

Albert Einstein, a renowned German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time, studied advanced subjects on his own, without the intervention of his teachers. He often cut classes to do so, which earned him the animosity of some of his professors, especially Heinrich Weber who refused to recommend him for any academic position.

Socrates and Einstein later followed academic careers and earned degrees. In spite of this great feat, Einstein’s professor, however, declined to recommend him for an academic chair.

What am I trying to bring out in this article? Degrees are important but they are not everything to teaching, learning, creativity and innovation. Just in the past, we can have very good and effective teachers, or creative and innovative people, without degrees. We can also have people who have degrees who cannot teach effectively or contribute meaningfully to the creative and innovative capital of a country or the world.

It is common these days to come across learners complaining, like Galileo did more than 450 years ago, that their teachers and professors do not put their own thinking and ideas in their teaching; that they regurgitate writings of others, which they coerce them to reproduce in examinations to earn grades and/or degrees. While the situation is not too bad in the West, it is becoming serious in poor countries such as Uganda where knowledge workers now find it a burden to read and write and/or what they write are reproductions of the minds of their lecturers and professors.

Many lecturers and professors are being compelled to spend far more time and energy making ends meet in a harsh socio-economic environment. Yet we know that if you spend 10 years without renewing or adding anything new to what you knew or skills you had when you checked out of school or university you become secondarily illiterate or secondarily uneducated. If, therefore, you acquired a degree or degrees, you are likely to manifest as if you never had a degree or degrees. Yet a lot of money, time and money were invested to produce you as a degreed person.

In the Uganda of today we have many degreed teachers who are still called teachers and paid by government for being professional and trained teachers, but spend more time and energy away from the classroom. The same is true of lecturers who have become allergic to the lecture theatres in the academia. In this case, having a degree as the determinant of who a teacher is or should be loses meaning. Many of us who now see teachers without degrees as useless were effectively taught by such teachers both at Primary and secondary levels.

There is need to rethink teaching and take it as the most critical factor in the renewability and sustainability of a knowledgeable society. However, it must be quality teaching for quality learning. Without this, a society is open to so many evils. The evils may even invade the education enterprise and reduce its usefulness and value to society now and in future. It will be useful to rethink the way we structure education to make it more holistic instead of continuing with the current education delivery in small bits with the falsehood that when the bits are put together, they will constitute the whole – the whole humanity, the whole community and the whole society. I have elsewhere emphasised the need to teach science as one with three dimensions – natural science, social science and arts (humanities) – while leaving room for non-disciplinary education under an integrated education curriculum. In this case, everyone’s education will be integrated in an integrated mind able to see the whole, not parts of the whole.

Indeed, the cyberage, which dominated the new millennium, demands a more open education curriculum that emphasises integrated non-degreed education even more while allowing joint and non-disciplinary scholarly work, which can be jointly rewarded. This is what reconnecting knowledge means: removing academic hegemony from the knowledge enterprise.

For God and my country.

- A Tell report / By Prof Oweyegha-Afunaduula, a former professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences of the Makerere University, Uganda