US records more firearm-related deaths than any other wealthy nation, 2020 was deadliest in 20 years

Maeve Wallace has studied maternal health in the United States for more than a decade, and a grim statistic haunts her. Five years ago, she published a study showing that being pregnant or recently having had a baby nearly doubles a woman’s risk of being killed.

More than half of the homicides she tracked, using data from 37 states, were perpetrated with a gun.

In March 2020, she saw something she hadn’t seen before: a funding opportunity from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study deaths and injuries from gun violence. She had mentioned firearms in her studies before. But knowing that the topic is politically fraught, she often tucked related terms and findings deep within her papers and proposals.

This time, she says, she felt emboldened to focus on guns specifically and to ask whether policies that restrict firearms for people convicted of domestic violence would reduce the death rate for new and expecting mothers. Male partners are the killers in nearly half of homicides involving women in the United States.

“This call for proposals really motivated me to ask the research questions that I may not have otherwise asked,” says Wallace, an epidemiologist at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Wallace’s group is one of several dozen funded by a new pool of federal money for gun-violence research in the United States, which has more firearm-related deaths than any other wealthy nation. Although other countries fund research on guns, it is often in the context of trafficking and armed conflict.

US federal funding of gun-violence research has not reflected the death toll, researchers say. The new money comes after more than two decades of what has essentially been a freeze on funding for the topic.

And that’s left a massive knowledge gap, says Asheley Van Ness, director of criminal justice at Arnold Ventures in New York City, a philanthropic organisation that pledged $20 million to gun research in 2018, in part because of the paltry federal funding. “For decades we just have under-researched basic questions on gun violence,” she says.

Spurred by advocacy that followed some high-profile school shootings, Congress has now authorised $25 million for each of the past two years to go to the NIH and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the study of gun violence as a public-health issue. In April, President Joe Biden suggested doubling that figure.

Although researchers were initially slow to answer the funding call, studies such as Wallace’s are starting to look at how gun policies affect homicide rates. Others will investigate strategies to reduce suicides, which typically account for nearly two-thirds of gun deaths in the United States. And a handful of state health departments around the country are getting funding to collect better statistics on gun-related injuries.

The opening of the tap for federal dollars is considered an important advance, but those who have been watching the field for years say it will take more money and consistent investment to attract a committed cohort of researchers and fill in the data gaps.

“That’s like turning a ship,” says David Studdert, who studies health law at Stanford Law School in California.

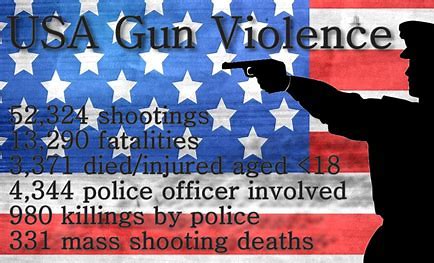

Meanwhile, gun violence in the United States shows no signs of slowing: 2020 emerged as the deadliest year in two decades, and the first few months of 2021 look even worse.

Federal funds for firearms research have been heavily restricted ever since the 1996 Dickey Amendment, a clause added to that year’s annual spending bill that barred the CDC from funding any effort that advocates or promotes gun control.

Although the amendment did not explicitly ban research on firearms, the CDC saw its budget cut by $2.6 million in the year it passed – the same amount the agency was spending on the topic. CDC administrators saw the move as a message to steer clear, says Andrew Morral, a behavioural scientist at the Rand Corporation in Washington DC and director of the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, a consortium of foundations that fund firearms research.

The amendment remained in subsequent spending bills, and researchers who continued to work on gun violence say that their work received more scrutiny.

“Any research we would put forward would create just a waterfall of backlash,” says Charles Branas, an epidemiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City.

The gun lobby would argue that the work was biased, Branas says. Lawmakers would start asking questions. “That’s not something a cancer researcher has to contend with,” he says. “I think it scared off a lot of potential young scientists.”

The result has been an anaemic level of funding for research on one of the top 20 causes of mortality in the United States. One 2017 estimate says that gun-violence research is funded at about $63 per life lost, making it the second-most-neglected major cause of death, after falls. Private foundations have tried to fill the gap, but the levels are still low.

The longest-running private funder, the Joyce Foundation in Chicago, Illinois, has invested $32 million since 1993; its annual funding has surpassed $2 million only once.

Things began to change after 2012 when a gunman shot and killed 20 children and 6 staff, before killing himself, at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut.

Amid a raging political fight over gun control, then-president Barack Obama called on federal agencies to fund research on the topic, triggering a call for proposals at the NIH (but not at the CDC, where funding is more tightly controlled by congressional appropriations).

- A Nature report