Africa is a complex continent. She is an eclectic mix of authoritarian regimes – where leaders have been in power for many decades; countries that are attempting to make their way towards democracy – even if progress is incremental and slow.

There are others that have had a stronger semblance of democracy for many years – though in honesty, they are still trying to find their feet.

As beautiful as Africa is, she is a continent scarred by war, tainted by corruption and in many instances lacking in transparency. For years there have been numerous attempts to bring the continent together to create a continent-wide common market – a free trade area where all can benefit. However, the attempts have yet to gain serious traction.

For a cohesive effort, you need common understanding and the ability to find common ground so that you can make decisions for the greater good of the continent rather than just your own country.

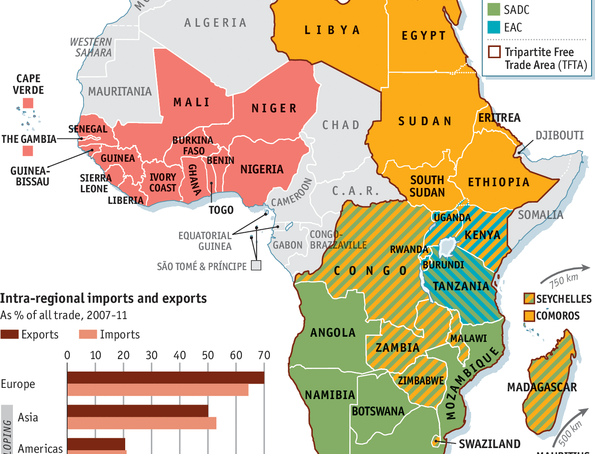

With such diverse politics and governance, however, that’s not easy to achieve. It is one of the reasons there are so many regional economic communities and why so many countries belong to more than one. There are eight recognised by the African Union and a further seven that AU does not recognise and overlaps occur in each.

So far, the most successful attempt at uniting sub-Saharan Africa has been the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which started trading on January 1.

AfCFTA presents enormous opportunities for Intra-African trade on the continent. It is about driving the continent’s agenda for growth rather than individual country’s designs. Intra-Africa trade has increased to 15.4 per cent over recent years, however, Asia and Europe are still the continent’s main trade partners.

Greater focus needs to be placed on raising Africa’s percentage of world production which is currently 2,9 per cent, and world trade which is currently 2,6 per cent. Unfortunately, many African countries have low performance in trade facilitation indicators, scoring low in e-commerce; linear shipping connectivity; and doing business indicators.

Lack of transparency and perceptions of corruption are also hindrances to intra- and inter-continental trade and sub-Saharan Africa is currently the lowest performing region on Transparency International’s CPI 2020: Sub-Saharan Africa Report.

In order to achieve her full capacity, Africa needs to look at alternative approaches to increasing revenue. In 2008, Seychelles President James Michel shifted his country’s strategic focus to what has become known as the Blue Economy. World Bank defines the Blue Economy as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem.

While it’s a concept that has been embraced globally, on the continent where the idea was born, we’re falling far behind.

The African Union (AU) has designated the years 2015-2025 as The Decade of African Seas and Oceans, and in February 2020, it launched the African Blue Economy Strategy in the Ethiopian capital Addis Abba.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa) and the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) also recognise the potential of the Blue economy as a lever of socio-economic development in their strategic documents.

According to the United Nations’ policy handbook on Africa’s Blue Economy, maritime zones under Africa’s jurisdiction total about 13 million square kilometres, including territorial seas and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and approximately 6.5 million square kilometres for the continental shelf (for which countries have jurisdiction over only the seabed).

The continent therefore has a vast ocean resource base that can contribute to sustainable development. In order to realise that sustainable development however, countries across the continent will need to collaborate, across borders and sectors on a scale they have not previously achieved.

The largest sectors of the current African aquatic and ocean-based economy are fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, transport, ports, coastal mining, and energy.

As PWC highlighted, African ports represent gateways for the continent’s commodity exports, but as countries grow and develop, ports are also essential for sustaining and improving more robust and diverse economic growth, through the import and export of manufactured goods and other products.

In Strengthening Africa’s Gateways to Trade, PwC’s analysis showed that based on the degree of port centrality (shipping liner connectivity), the amount of trade passing through a port, and the size of the hinterland, Durban (South Africa), Abidjan (Cote d’Ivoire) and Mombasa (Kenya) are most likely to ultimately emerge as the major hubs in Southern Africa, West Africa and East Africa, respectively.

The report stated that the closest rivals to these ports are Lagos-Apapa (Nigeria) and Tema (Ghana) as alternatives to Abidjan and Djibouti and to a lesser extent Dar es Salaam to Mombasa. Due to their better operational performance, both Lagos-Apapa and Tema pose significant challenges to Abidjan’s emergence as a hub, which might eventually be decided on factors such as on political stability, port performance and quality of inland connections.

Improving port performance, could increase GDP by two per cent. An efficient port reduces delays to shippers, reduces overall logistics costs, and improves reliability of goods in transit. Yet across Africa, investment in port infrastructure and expansion has slowed.

- A Tell opinion/ Mokrane Sabri is a senior trade manager and maritime expert for North Africa & Middle East