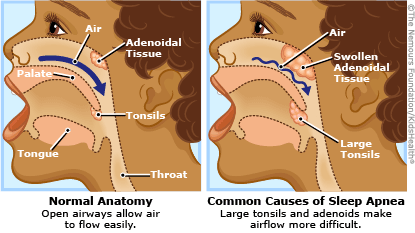

For African Americans, markedly higher rates of sleep apnea sabotage slumber, says Girardin Jean-Louis, a sleep researcher at New York University. One reason for this difference is that non-Hispanic Blacks are 1.3 times as likely to be overweight or obese as non-Hispanic whites, federal data show, and this excess weight can partially close off breathing during sleep.

During sleep studies, Jean-Louis and his fellow researchers have seen people waking up as often as 200 times a night – a predicament that can become a cruel trap. Poor sleep can affect people’s metabolism and even the hormones that regulate appetite, leading to further unhealthy weight gain.

Stress is an additional impediment to sleep – and socially and financially disadvantaged people, not surprisingly, tend to have more of it. Financial problems, a relative lack of control over one’s life, and systematic racism can all interfere with getting sufficient rest, Troxel says.

Blacks, for example, consistently report more job-related stress than whites. On average they are more likely to work in jobs with little sense of control, work at more than one low-wage job at a time and live in poverty even when employed, research shows.

In a sad irony, however, even as whites tend to sleep better as they advance in their careers and become more responsible at work, the opposite is true for Blacks. The specific reasons remain unknown, but some researchers cite “John Henryism” – named after the legendary Black “steel-driving man” – in which Black people overwork to prove they can succeed.

As Jean-Louis and other researchers have found, Blacks tend to spend less time than whites in slow-wave sleep, the deep slumber that supports physical and mental health. In a longitudinal study involving home and lab studies of 210 elderly people, including 150 African Americans, Jean-Louis is exploring the degree to which this deficit may contribute to higher rates of heart disease and dementia.

Whatever its causes, the sleep divide creates a devastating vicious cycle. Poor sleep makes people less healthy, which in turn may further trouble their sleep. And in yet another malicious feedback loop, poor sleep can contribute to more vehicle accidents and reduced productivity and income. All of which, of course, create more reasons to toss and turn.

Two photos. Upper panel shows a noisy urban scene, with apartment blocks above an elevated subway track and large road. Lower panel shows an aerial photo of a quiet, green suburb.

Not surprisingly, people in wealthier neighbourhoods sleep better, at least partly because poorer neighbourhoods tend to be noisier and have less green space. Upper image shows a noisy urban neighbourhood near Coney Island, New York. Lower image shows a middle-class suburb in San Antonio, Texas.

Some of the reasons for the sleep divide are profound and depressingly familiar, having bedevilled policymakers for decades. There’s frankly little hope that any of the huge issues researchers cite, such as poverty, racial discrimination and environmental injustice, will be solved anytime soon.

Still, Troxel and other scientists say the new attention to sleep is a major step forward, guiding them to imagine smaller “socioecological” steps to improve sleep health and its cascade of consequences.

“In many cases sleep health is modifiable,” says Rebecca Robbins, a sleep researcher at Harvard Medical School.

Troxel, Robbins and Jean-Louis have all been focusing on strategies to do just this. In New York City, Jean-Louis has been recruiting barbers and church leaders as local ambassadors to spread the word about sleep health. “The patients just aren’t coming to the clinic or the hospital,” he says. “We have to go to them.”

Jean-Louis has teamed up with Robbins and other researchers to adapt videotaped educational materials about sleep apnea that featured older white men to include narratives from Black people. They’ve installed these videos on iPads that they distribute to local barbershops and churches.

Poorer people, and racial minorities, are more likely to hold shift-work jobs that prevent them from getting a normal night’s sleep. Here, paper-mill workers in Maine head home mid-morning at the end of a shift.

Sleep hygiene education is sorely needed, Jean-Louis adds, given the depth of public misunderstanding about common sleep disorders. He says he’s often been dismayed, for instance, to hear people insist that snoring is a healthy sign of deep sleep, when in fact it often signals a problem such as sleep apnea. His usual response is to say, “This is God’s way of saying there’s something wrong.”

Changes in laws and regulations could also go far to improve sleep health, according to Jean-Louis and Troxel. Improved local noise ordinances, building codes for reducing light pollution, and more humane schedules for overnight shift work, which is more prevalent among African Americans, could all help reduce the sleep divide.

Major national debate has focused on one relatively straightforward change, which scientists contend could help tens of millions of Black, white, rich and poor children and their families sleep better: namely, delaying school start times by as much as an hour. The science is solid. For their physical and mental health, teens need a lot more sleep than they’re getting.

Many school districts that have moved back their starting clocks have seen benefits including more alert students, better academic outcomes and fewer car accidents. So far, however, fewer than 20 per cent of US middle and high schools have made the change, Troxel notes.

When schools closed for the pandemic, many set their remote schedules later, and some surveys of students suggest that this has allowed students more sleep.

A paradigm shift is implied in all of these sleep strategies. Sleep has traditionally been seen as a purely individual responsibility: Don’t drink coffee at night; keep the room dark; don’t look at your phone in bed, etc. Troxel, Jean-Louis and other scientists argue that we need to widen our perspective to reimagine sleep as a public health opportunity.

“We need to think of population-level interventions,” says Troxel, “including policies to ensure that healthy sleep is not merely a luxury for those who can afford it.”

- A Knowable Magazine report