Ranked-choice voting (here called instant-runoff voting) can also be used for contests that decide several seats at once, such as races for city councils or school boards. The counting is more involved, but the goal is to produce a slate of winners that roughly matches the partisan makeup of the electorate.

For example, if there were five seats at play in a district that was divided 60-40 between Democrats and Republicans, the current system would usually elect five Democrats – effectively leaving two-fifths of the electorate with no representation. The ranked-choice system would come closer to three Democrats and two Republicans.

But ranked-choice voting’s promise of reducing division and extremism is quite real, says Reilly; he found compelling evidence for the effect with his thesis work in Papua New Guinea.

“The place is extremely fragmented along ethnic lines, with all these micro-clans and tribes,” he says. Yet back in the 1960s, when the area was under Australian colonial administration and used its ranked-choice rules, elections were surprisingly civil. “The studies from that period all talked about how there were these deals being done between tribal and clan groups to get second votes” from one another’s supporters, Reilly says.

But with independence in 1975, he says, Papua New Guinea adopted US-style plurality voting instead. By the time Reilly started his research there in the 1990s, he says, “the incentives to do deals and trade-offs had completely disappeared. People were winning elections with five and six percent of the vote, because there were 60 candidates standing sometimes.”

And with officials taking office with almost no support, he says, “that was leading to a lot of tribal violence, and other problems.”

Things calmed down a bit after 2003, when Papua New Guinea went back to ranked-choice voting and the dealmaking re-emerged. It remains a deeply troubled country, says Reilly, who has found comparable alliance-building in Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Fiji and other divided regions that have adopted ranked-choice voting. “But it was a really interesting natural experiment of what can happen under two different electoral systems.”

Similar, if less dramatic, alliances have already started popping up in Maine, San Francisco and other US ranked-choice jurisdictions. A particularly well-publicised example came late in the New York primary campaign, when candidates Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia seem to have tried to counter front-runner Adams by appearing together, with Yang asking his voters to rank them first and second.

It didn’t work: Adams won anyway. But even so, says Richie, look for more such collaborative campaigning as politicians get used to the logic of ranked-choice voting. In his own town of Takoma Park, Maryland, where it’s been used since 2007, “I’ve seen candidates walk past a yard sign for their opponent and knock on the door to talk to someone anyway,” he says. Getting one more second-choice ranking can matter.

That said, however, there remains one crucial question that only time can answer.

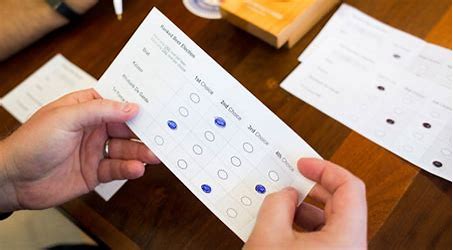

Although Eric Adams had the most votes after the first round of counting in New York City’s 2021 Democratic mayoral primary, most voters preferred someone else. But his support proved broad enough to keep him in the lead as trailing candidates were eliminated and their votes redistributed. After eight rounds, Adams could claim majority support.

There is still ample reason for skepticism on that score – not least because ranked-choice voting has already failed here once. Versions of the system were used for local elections in some two dozen US cities during the first half of the 20th century, only to be repealed almost everywhere as party bosses fought back against their loss of control.

By 1962, the sole survivor was Cambridge, Massachusetts; it would stand alone until 2004, when San Francisco became the first city in the modern era to start routine use of ranked-choice voting.

The current wave of adoptions hasn’t always gone smoothly, either. In 2020, for example, Massachusetts voters rejected ranked-choice voting by close to a 10-percentage-point margin.

“Voters didn’t see a clear problem it was solving, says Tyler Fisher, senior director of policy and partnerships at Unite America, a Denver-based non-profit that supports a variety of electoral reforms.

Then, too, today’s revival of ranked-choice voting comes at a time of profound mistrust in our election system in general – by both sides.

- A Knowable Magazine report