Haematologist Mitesh Borad at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Arizona, and his colleagues have analysed the structure of the chimpanzee adenovirus used in the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and determined that it has a strong negative charge.

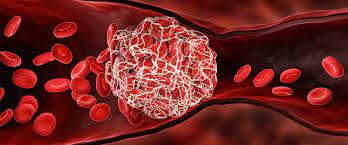

Molecular simulations suggest that this charge, combined with aspects of the virus’s shape, could allow it to bind to the positively charged PF4 protein. If so, it could then set off a cascade much like the rare reaction to heparin, says Borad, although it remains to be seen whether this happens.

Even if the adenovirus is to blame, Borad says he would not advocate that vaccine developers stop using adenoviruses in vaccines. Some adenoviruses could be engineered to reduce their negative charge, he says, and some are less negatively charged than others; the Ad26 adenovirus used in the J&J Covid-19 vaccine does not have as much of a charge as the chimpanzee virus, which might explain why VITT seems to be less common in recipients of the J&J vaccine.

And so far, no link to VITT has been reported for the Sputnik V Covid-19 vaccine, which uses both Ad26 and another adenovirus called Ad5 that has still less negative charge, he adds.

Then there’s the spike protein itself. One team of researchers wondered whether the antibodies that bind to PF4 in people with VITT are an unintended by-product of the body’s immune response to spike. But they found that the PF4 antibodies can’t bind to it, suggesting that they are not part of the immune response to the viral protein.

But cancer researcher Rolf Marschalek at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany and his colleagues have shown that the snippets of RNA that encode spike can be cut apart and stitched back together in different ways in human cells; some of these forms, called splice variants, can generate spike proteins that get into the blood and then bind to the surface of cells that line blood vessels.

There, they cause an inflammatory response that is also seen in some SARS-CoV-2 infections, which in severely affected people can lead to the formation of clots.

And the lower rate of clots in J&J’s vaccine compared with Oxford-AstraZeneca’s could be because the version of spike generated by the J&J vaccine was engineered to remove the sites that allow the RNA to be processed into splice variants, says Marschalek.

Marschalek thinks that if this idea is borne out, then the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and other adenovirus-based vaccines could be rendered safer if their versions of spike were similarly engineered.

There are reports that the teams behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines are working to develop safer adenoviral vectors, and Marschalek says he would be surprised if companies abandoned adenoviral vectors altogether. Others agree.

“I think they are very popular and will remain popular,” says Othman, citing the ease with which the vaccines can be produced and manipulated, and the wealth of data suggesting that, for most people, the vaccines are safe. Instead of abandoning them, she says, “we should study more about the immune responses to them.”

One possible factor affecting the safety of adenoviral vaccines is how they are administered. The Covid-19 vaccines are given as injections into muscle, but if the needle happens to puncture a vein, the vaccine could enter the bloodstream directly. Leo Nicolai, a cardiologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, and his colleagues found in a mouse study that platelets clump together with adenovirus and become activated when the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is injected into blood vessels, but not when it is injected into muscle.

It’s possible, says Nicolai, that on rare occasions, a vaccine is inadvertently injected into a vein – as was done in the earlier mouse studies that found that adenovirus could bind to platelets. If so, many cases of VITT might be avoided by asking vaccinators to first draw a small amount of fluid from the injection site with the syringe to check for blood before they actually push the plunger to administer the vaccine.

This is already standard practice in some countries, and Denmark has added it to its official guidelines for Covid-19 vaccine administration.

Better treatments are still needed for VITT, which according to a UK study killed 49 of the 220 people who were diagnosed with the condition between March and June 2021. Currently, doctors treat VITT by giving anti-clotting treatments other than heparin, and administering high doses of naturally occurring antibodies from blood-plasma donors. The antibodies compete with the anti-PF4 antibodies for binding sites on platelets, and reduce the latter’s ability to promote blood coagulation.

“The hope is to try to confuse the body and hide the dangerous antibodies within a huge fog of normal antibodies,” says Kelton. “That’s a very, very blunt tool.”

In Birmingham, Nicolson has been working to develop more-specific approaches. He has tested blood serum from people with VITT to see whether he can repurpose drugs developed for other conditions to treat it.

In particular, he is focusing on treatments that interfere with a protein on platelets, to see whether any drugs can prevent platelet activation and the cascade of events that leads to clots in VITT.

But even if he were ready to launch a clinical trial of these therapies, there are few people in whom to test them. Since he saw the first cases in March, the United Kingdom has changed its vaccination policy, and now recommends the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine only for people over 40.

VITT is more frequent in younger vaccine recipients, possibly because of their more-robust immune responses.

It is unclear whether other countries will have the same luxury of restricting Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines to older people, given that it is relatively cheap and widely available compared with the mRNA vaccines, for example.

Until now, VITT has primarily been reported in Europe and the United States, but researchers don’t yet know whether this reflects regional differences in susceptibility to VITT, or differences in reporting systems that gather data on potential vaccine side effects.

In Thailand, for instance, researchers reported in July that there had been no cases of VITT after 1.7 million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine were given12.

Nicolson says the number of people referred to his hospital with VITT has declined drastically: “We’re not seeing it any more, it’s almost stopped happening.”

- A Nature report