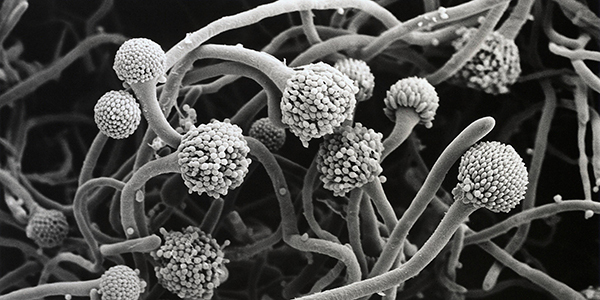

As rates of antibiotic resistance grow alarmingly among disease-causing bacteria, dangerous fungi also are evolving stronger defences, with a lot less fanfare.

Every year, infections of moulds and yeasts such as Aspergillus and Candida kill more than 1.5 million people globally, more than malaria and on a par with rates for tuberculosis. And new drug-resistant strains are emerging, such as Candida auris, first detected in Japan in 2009 and since then reported on every continent except Antarctica.

Between September 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021, the number of reported C. auris cases in the United States has soared to over 1,100 in 21 states, up from 63 cases in four states from 2013 to 2016.

With Covid-19 cases stressing healthcare systems, changes in hospital infection control have given drug-resistant fungi a leg up, too. In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention listed C. auris as an urgent threat; it was the first time the agency had done so for a pathogenic fungus. In December 2020, the CDC reported increased spread of C. auris during the pandemic.

Put simply, “fungal infections are a massive public health problem,” says Johanna Rhodes, a genomic epidemiologist of fungal infections at Imperial College London. There are few drugs to fight them, and the pipeline for development of new ones has been frustratingly slow.

Today, though, a few novel antifungals are moving through clinical trials and researchers are developing new approaches to drug discovery that may ultimately strengthen the antifungal arsenal. In the meantime, healthcare organisations are working on improved practices to help stall the development of resistance in these problematic microbes.

Fungal pathogens become life-threatening when they get inside the body, infecting the bloodstream and internal organs. Such invasive infections have become more common due to the evolution of drug resistance as well as life-saving medical advancements such as organ transplants and cancer therapies that have created a growing population of immunocompromised people. The armamentarium of drugs to fight them is limited – and dated.

The first antifungal for treating invasive infections, amphotericin B, came out in 1958 and works against a variety of fungi. A member of the antifungal class known as polyenes, amphotericin B binds to key molecules – ergosterols – and extracts them from the fungal cell membrane, thereby damaging the cell’s functions. The drug’s toxicity to patients limits its use.

Beginning in the late 1970s, doctors also had a new, less toxic class of antifungals to turn to: azoles, which prevent fungal cells from making ergosterol. Then, in the early 2000s, a third class, the echinocandins, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for medical use. These drugs act by blocking production of a carbohydrate called beta-D-glucan, a vital part of fungal cell walls.

Resistance to azoles slowly emerged in the 1990s, due in part to agriculture. The industry had begun using azole fungicides to protect crops from fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus, a common mould in the 1970s. Later, azole-resistant A. fumigatus infections in people began cropping up, becoming more common after 2003.

People with no previous exposure to medical azoles were turning up with resistant infections, a telling sign that they had picked up A. fumigatus from the environment, for example from gardens or soil.

Medical use of antifungals has also pushed pathogens to evolve new defences. Problems include the failure of patients to finish a course of drugs, as well as improper prescribing – for example starting antifungals in someone with an asymptomatic infection, prescribing the wrong drug or dose, or prescribing too long a course.

Physicians must also strike a delicate balance between preventing deadly infections in immunocompromised patients and trying to limit opportunities for fungi to evolve resistance. They often prescribe antifungals as a preventive measure in such patients which, though protective, also encourages resistant fungi if use is prolonged.

In hospitals, invasive fungal infections featuring drug resistance are increasingly problematic. C. auris infections, almost always acquired in healthcare facilities, increased by over 100 cases each year from 2017 to 2019, when 469 cases were reported, jumping to 746 cases in 2020, according to the CDC. And in the 12 months from September 2020 through August 2021 there were 1,156 reported cases.

Catheters, intravenous lines and ventilators provide ample opportunities for pathogens to enter new hosts. “These are absolute highways for these environmental agents to get into the human body,” says Rodney Rohde, a microbiologist at Texas State University.

Covid-19-associated invasive fungal infections have cropped up too – most commonly pulmonary aspergillosis (generally Aspergillus fumigatus), but also black fungus (caused by soil fungi called mucormycetes) and infections with Candida, including C. auris.

According to the CDC, overstretched healthcare facilities have struggled to uphold normal infection control procedures, such as cleaning medical equipment and rooms and screening for C. auris.

Today, 90 per cent of C. auris samples from infected patients are resistant to at least one antifungal drug, typically fluconazole, and 30 per cent are resistant to at least two. But during the pandemic, C. auris infections that are resistant to all antifungal drugs also have been detected – the first examples of pan-resistant C. auris transmission in US health care facilities.

People with invasive fungal infections “are very sick patients and we don’t have very good diagnostic tests. We don’t have very good treatment options,” says Jose Lopez-Ribot, a medical mycologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio. And this isn’t just a risk for people with compromised immunity.

“Any of us, even the general public, can go in for a routine surgery and can end up sick in a hospital – that’s when you’re going to be at risk for these infections,” says Tom Chiller, chief of the CDC’s mycotic diseases branch. “You want there to be drugs available for you to use.”

Candida auris is a dangerous yeast, first identified in 2009, that is often resistant to multiple antifungals and sometimes to all three classes of those drugs. This chart shows how known cases of invasive C. auris have risen in the United States. C. auris cases are usually found in long-term health care facilities.

- A Knowable Magazine report