A woman of mixed race appears to be the third person ever to be cured of HIV, using a new transplant method involving umbilical cord blood that opens up the possibility of curing more people of diverse racial backgrounds than was previously possible, scientists announced on Tuesday.

Cord blood is more widely available than the adult stem cells used in the bone marrow transplants that cured the previous two patients, and it does not need to be matched as closely to the recipient. Most donors in registries are of Caucasian origin, so allowing for only a partial match has the potential to cure dozens of Americans who have both HIV and cancer each year, scientists said.

The woman, who also had leukemia, received cord blood to treat her cancer. It came from a partially matched donor, instead of the typical practice of finding a bone marrow donor of similar race and ethnicity to the patient’s. She also received blood from a close relative to give her body temporary immune defenses while the transplant took.

Researchers presented some of the details of the new case on Tuesday at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Denver, Colo.

The sex and racial background of the new case mark a significant step forward in developing a cure for HIV, the researchers said.

“The fact that she’s mixed race, and that she’s a woman, that is really important scientifically and really important in terms of the community impact,” said Dr Steven Deeks, an AIds expert at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the work.

Infection with HIV is thought to progress differently in women than in men, but while women account for more than half of HIV cases in the world, they make up only 11 per cent of participants in cure trials.

But Dr Deeks said he did not see the new approach becoming commonplace. “These are stories of providing inspiration to the field and perhaps the road map,” he said.

Powerful antiretroviral drugs can control H.I.V., but a cure is key to ending the decades-old pandemic. Worldwide, nearly 38 million people are living with H.I.V., and about 73 percent of them are receiving treatment.

A bone marrow transplant is not a realistic option for most patients. Such transplants are highly invasive and risky, so they are generally offered only to people with cancer who have exhausted all other options.

There have only been two known cases of an HIV cure so far. Referred to as “The Berlin Patient,” Timothy Ray Brown stayed virus-free for 12 years, until he died in 2020 of cancer. In 2019, another patient, later identified as Adam Castillejo, was reported to be cured of HIV, confirming that Mr Brown’s case was not a fluke.

Both men received bone marrow transplants from donors who carried a mutation that blocks HIV infection. The mutation has been identified in only about 20,000 donors, most of whom are of Northern European descent.

In the previous cases, as the bone marrow transplants replaced all of their immune systems, both men suffered punishing side-effects, including graft versus host disease, a condition in which the donor’s cells attack the recipient’s body. Mr Brown nearly died after his transplant.

Mr Castillejo’s treatment was less intense, but in the year after his transplant, he lost nearly 70 pounds, developed a hearing loss and survived multiple infections, according to his doctors.

By contrast, the woman in the latest case left the hospital by day 17 after her transplant and did not develop graft versus host disease, said Dr JingMei Hsu, the patient’s physician at Weill Cornell Medicine. The combination of cord blood and her relative’s cells might have spared her much of the brutal side effects of a typical bone marrow transplant, Dr Hsu said.

“It was previously thought that graft versus host disease might be an important reason for an HIV cure in the prior cases,” said Dr Sharon Lewin, president-elect of the International Aids Society, who was not involved in the work. The new results dispel that idea, Dr Lewin said.

The woman, who is now past middle age (she did not want to disclose her exact age because of privacy concerns), was diagnosed with HIV in June 2013. Antiretroviral drugs kept her virus levels low. In March 2017, she was diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia.

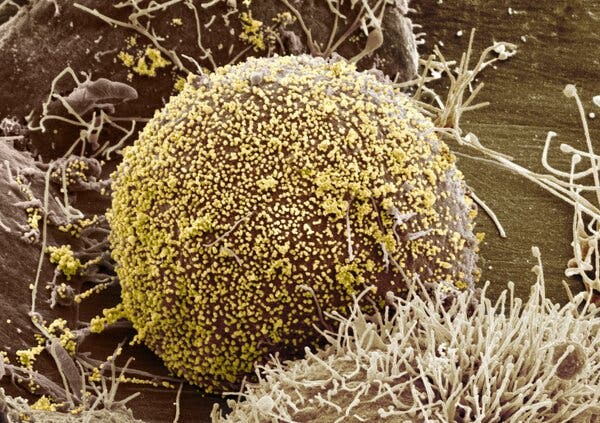

In August of that year, she received cord blood from a donor with the mutation that blocks H.I.V.’s entry into cells. But it can take about six weeks for cord blood cells to engraft, so she was also given partially matched blood stem cells from a first-degree relative.

The half-matched “haplo” cells from her relative propped up her immune system until the cord blood cells became dominant, making the transplant much less dangerous, said Dr Marshall Glesby, an infectious diseases expert at Weill Cornell Medicine of New York and part of the research team.

“The transplant from the relative is like a bridge that got her through to the point of the cord blood being able to take over,” he said.

The patient opted to discontinue antiretroviral therapy 37 months after the transplant. More than 14 months later, she now shows no signs of HIV in blood tests, and does not seem to have detectable antibodies to the virus.

It’s unclear exactly why stem cells from cord blood seem to work so well, experts said. One possibility is that they are more capable of adapting to a new environment, said Dr Koen Van Besien, director of the transplant service at Weill Cornell. “These are newborns, they are more adaptable,” he said.

Cord blood may also contain elements beyond the stem cells that aid in the transplant.

“Umbilical stem cells are attractive,” Dr Deeks said. “There’s something magical about these cells and something magical perhaps about the cord blood in general that provides an extra benefit.”

- A New York Times report