Six million people or 40 per cent of the population in Somalia is “acutely food insecure”, according to data captured by United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The number includes 81,000 people already at a “catastrophe” level of hunger, with a real risk of famine in multiple areas of the country this year. Yet the humanitarian response plan is only 18 per cent funded.

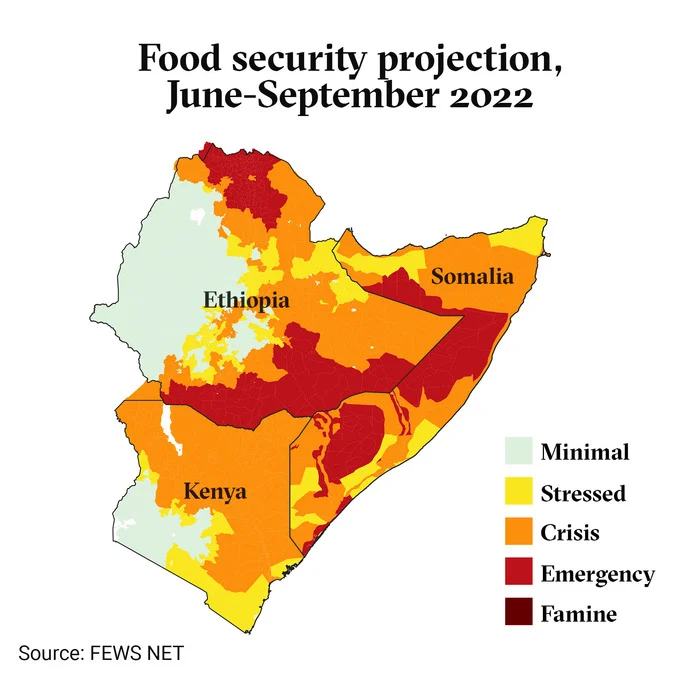

Areas particularly badly affected include pastoralist regions in the northeast and the centre of the country, as well as the informal displacement camps around the capital, Mogadishu and the towns of Baidoa in the southwest and Dhusamareb in the centre.

There has also been a sharp rise in child and adult mortality rates in the south, despite it being relatively accessible for aid deliveries.

More than 770,000 people have abandoned their homes in the current drought, looking for water and pasture for their animals, or help for themselves. That’s double the number displaced during the 2016/17 drought emergency, and could reach 1.4 million people in the next six months.

Ethiopia is facing two food emergencies: One is the conflict in the north, which has left more than nine million people in Tigray, Afar and Amhara in need. The other is the drought in the eastern and southern lowlands, affecting 6.8 million people.

A humanitarian ceasefire between the federal government and Tigray rebels agreed in March has not translated into the flood of food aid needed to ease “famine-like” conditions.

Meanwhile, the arid regions of Somali, Oromia, and Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ (SNNP) have struggled with two years of back-to-back droughts that have left pasture conditions among the driest on record.

An estimated 2.5 million livestock died between late 2021 and mid-May 2022. It’s not only a significant knock to household prosperity, it also removes milk – a key source of nutrition for children – from people’s diets.

There has also been a drastic fall in terms of trade for remaining animals. The sale of a goat last year would have covered a family’s food needs for 23 days – now it’s down to just six days.

In Kenya, more than four million people – a quarter of the population in the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASAL) in the north and eastern – are acutely food insecure. The numbers in need could rise to five million as conditions deteriorate.

Staple food prices have continued to rise, with maize 12 to 46 per cent above the five-year average. Mass screening by UNICEF in Marsabit county in February found a child malnutrition rate of 23 per cent – well above the 15 per cent standard emergency threshold.

With an anticipated failed harvest in June, and worsening pasture conditions for livestock, hunger levels are set to deepen.

As is also the case in Ethiopia, the government’s welfare safety net programme has been overwhelmed by the scale of the crisis. But political attention has also wandered, diverted by upcoming elections in August this year.

More than 70 per cent of South Sudanese are dependent on food aid – the consequence of conflict, under development, and a poorly performing government. Three consecutive years of floods have also eroded people’s ability to produce or purchase food.

As a result, three million people are facing a food emergency. In eight counties, households are already at “catastrophe” levels of hunger, with a strong likelihood of famine in some of the most vulnerable areas.

The most dangerous period will be July to August, coinciding with the traditional lean season and the height of the rainy season.

Sudan is struggling with the convergence of conflict, economic and political crisis and a poor harvest, with as many as 18 million people or 40 per cent of the population projected to be short of food by September.

Conflict continues to drive displacement and food insecurity in western Darfur. But there have also been poor harvests in South Kordofan, Blue Nile, Kassala, Red Sea states, and North Kordofan, depressing overall cereal production.

In April, staple food prices increased on average by 10 to 15 per cent compared to March – and up 200 to 250 per cent more than in 2021. Devaluation of the local currency, and higher transportation costs, helped fuel inflation. Sudan is also particularly dependent on now-blocked wheat imports from the Black Sea region.

Sudan’s economic woes are unlikely to ease soon. Western financial support was frozen when a beleaguered military government, challenged daily by pro-democracy protesters, seized power last year.

- The New Humanitarian report