Twenty years ago, cardiologist and stem-cell scientist Piero Anversa published an exciting paper. He was then a prominent researcher at New York Medical College in Valhalla, and his data in mice showed that injured hearts could regenerate with the help of stem cells taken from bone marrow – contrary to prevailing wisdom.

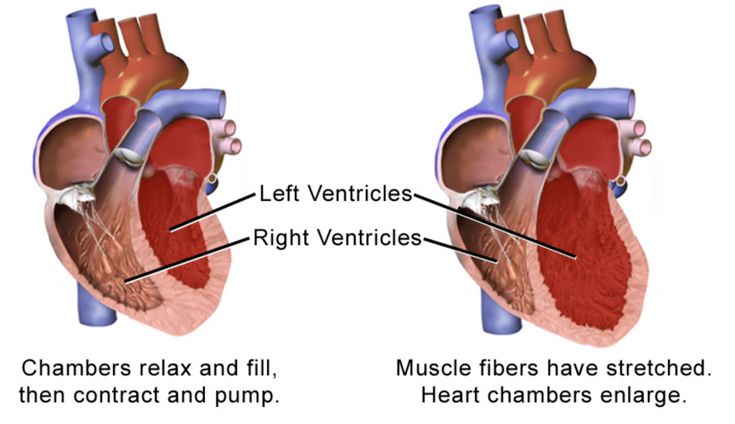

Myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack, deprives cardiac muscle cells of oxygen, causing them to perish. The human heart responds by laying scar tissue over lost muscle. But these reconstituted areas don’t pump blood as competently as before. In time, this can lead to heart failure – particularly if other heart attacks follow.

The implications of Anversa’s work were clear: stem cells, through their growth and proliferation, had the potential to reverse the damage caused by heart attacks and thereby prevent heart failure.

But other researchers who attempted to replicate these mouse studies found themselves coming up short. Allegations of faked results eventually began to surface, and Anversa, who had since joined Harvard Medical School, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, was forced to leave his posts in 2015.

Two years later, Brigham and Women’s Hospital paid the US government $10 million to settle allegations that Anversa and his colleagues had used fraudulent data to apply for federal funding. And a 2018 investigation conducted by Harvard called for 31 of Anversa’s papers to be retracted.

This saga has dampened the enthusiasm that once surrounded research into stem-cell therapy, says Michael Schneider, a research cardiologist at Imperial College London.

“The controversy, overt scientific misconduct and evidence against Anversa’s claims has cast aspersions on the field more generally,” he admits. That’s unfortunate, because many other stem-cell scientists are conducting legitimate research.

Meanwhile, another heart-healing strategy has emerged, drawing inspiration from species that, unlike humans, can regrow cardiac muscle after trauma. Researchers are seeking to learn more about the molecules produced by zebrafish (Danio rerio) hearts as they heal themselves – and are investigating whether injectable drugs containing the same substances could also yield reparative results.

The question is now whether it will be stem cells, small-molecule drugs or a combination of the two that achieve the goal of convincing the heart to heal instead of scar.

In the wake of the Anversa scandal, there has been an important evolution of thinking on the stem-cells front. A 2019 literature review pointed out that newer studies tend to show the most significant impact from stem-cell therapy comes from the substances the cells secrete, rather than their proliferation.

“After many years of work, we find that when we deliver cells into the heart, the benefit of replaced damaged cells is only minor,” says the review’s author Javaria Tehzeeb, an internal-medicine specialist at the Albany Medical Center in New York. The real work of regeneration happens, she explains, when the cells produce growth factors, which in turn affect heart repair by reducing inflammation and stimulating the development of new heart muscle.

That means stem-cell therapies share some similarities with the drug strategy – essentially it comes down to molecules secreted by the stem cells versus molecules that are directly injected. But they also have important differences.

First, part of the stem-cell therapy benefits might still come from the cells’ proliferation, even if that bonus is relatively small. Second, there’s little control over what substances the stem cells produce once they’re injected, whereas specific molecules can be administered at known doses. And finally, the logistics of scaling up and delivering these two therapies will be very different.

A study published in 2020 showcased the importance of stem-cell-produced molecules by looking at the structural integrity of proteins found in infarcted mouse hearts. The scientists artificially induced heart attacks in eight adult mice.

Four weeks later, they administered stem cells to half the rodents. After a further four weeks, their hearts were removed and washed with a series of buffer solutions and chemical reagents to extract the proteins, which were then analysed.

“We essentially did a massive scan of every single protein in the heart,” says Andre Terzic, lead author of the study. The authors were able to identify almost 4,000 proteins, and showed that heart attacks distorted the structure of 450 of them. But with stem-cell therapy, that number fell to 283.

“Proteins are the intimate components that make our hearts work properly and when the heart is diseased, they become damaged,” says Terzic, who is director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota. “The ability of these stem cells to secrete healing signals is probably a key element to what we’ve observed.”

- A Nature magazine report