After Twitter drew world attention to schoolgirls abducted by Boko Haram terror group, Nigerian security forces began to arrest protesters and later deployed armed police and water cannons onto the median. That scene would only provide more arresting footage to help drive the story further up the Twitter algorithm.

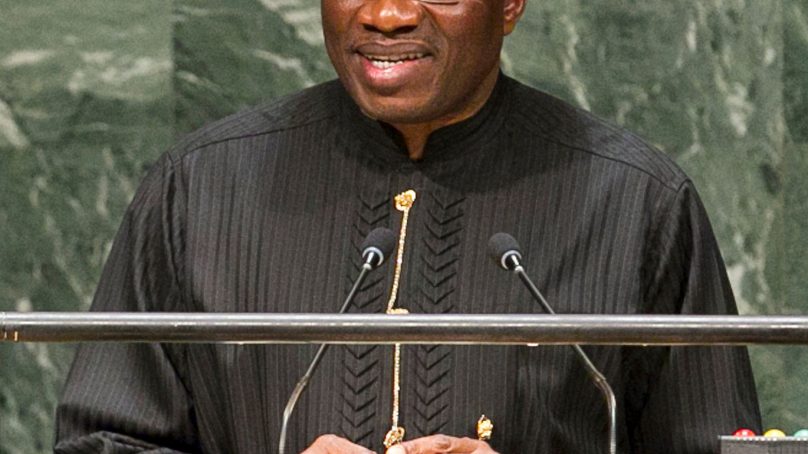

Nigeria President Goodluck Jonathan’s officials were not going to silence Ezekwesili, a formidable former education minister, who had called support from her 128,000 Twitter followers, easily.

Quietly, Oby was deploying other, less public strategies to outmanoeuvre them. As the story gained traction in US media, she typed out a series of messages to John Podesta, a colleague she had known from her time working in Washington who was now a senior counsellor in the White House: Do you think Hillary Clinton could tweet about this?

Podesta forwarded the request to Cheryl Mills, the former secretary of state’s long-time adviser. At 12:05 pm on May 4, in Chappaqua, New York, @HillaryClinton posted a tweet: “Access to education is a basic right & an unconscionable reason to target innocent girls. We must stand up to terrorism. #BringBackOurGirls.”

Twenty-five thousand retweets quickly followed. Jonathan was bringing analogue weapons to a digital fight. After Clinton’s tweet, some of America’s most influential political figures joined the campaign. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi held a moment of silence on the steps of the Capitol, joined by Republican senator Tim Scott.

“What has happened in Nigeria is outside the circle of civilised human behaviour,” Pelosi said. Civil rights hero John Lewis added his voice. Inside the chamber, Miami congresswoman Frederica Wilson, famed for her collection of sequined cowboy hats, convinced dozens of members of Congress to dress in red every Wednesday in solidarity until the schoolgirls came home.

For President Jonathan, the host of a summit now ruined before it began, the story could not get any bigger or worse. And then, shortly after 1 pm on May 5, a video appeared on YouTube.

“I abducted your girls,” said Boko Haram’s leader Abubakar Shekau, grinning in combat fatigues, his chin raised triumphantly. Standing in a forest clearing, flanked by six masked gunmen, Africa’s most wanted man had finally captured the world’s attention and he was elated.

The lens zoomed in to show his rifle swinging in front of his bulletproof vest as he chopped his arms in the air. “I will sell them in the market, by Allah! I will marry off a woman at the age of twelve. I will marry off a girl at the age of nine.”

This was petrol for a Twitter fire. The story now had a ticking clock and a clear villain. Within minutes, screenshots and article previews bearing Shekau’s menacing grin were flying across Twitter and it was trending, sparking new convulsions of outrage and millions more endorsements for #BringBackOurGirls.

Footage of the warlord played on loop on cable news, a pantomime TV villain that helped highlight a six-year-old insurgency as a contest of good versus almost unfathomable evil. Anchors choked up as they presented packages on the madman who had taken our girls.

In London, hundreds of demonstrators thronged the Nigerian embassy, holding matching “No child born to be taken” placards. Another crowd swarmed the United Nations in Manhattan. British parliamentarians wrote to Prime Minister David Cameron to ask what action the UK would take in its former colony.

In a letter to the White House, 20 women in the Senate wrote, “The girls were targeted by Boko Haram simply because they wanted to go to school and pursue knowledge. The United States must respond.” None of them seemed aware that the insurgency had been trying to steal a brickmaker.

Condemnations of Boko Haram were morphing into the language of a military intervention. Conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh was lambasting the White House for being soft on terrorism, asking, “Is the United States really this powerless?

And then if you answer yes, we are really this powerless, then isn’t Obama to blame?” Senator Dianne Feinstein was demanding that US special forces stage a rescue mission and if the Nigerian government didn’t approve one, then ordinary Nigerians should lift their voices and demand that their leaders open their soil up to American troops. Whatever it took, she said, to locate, capture and kill the men who’d done this.

In a meeting in the White House’s John F. Kennedy Situation Room, deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes had been watching the hashtag’s metrics and asking what precisely the endgame was.

“Even if it hits a billion tweets, do we think Boko Haram is going to throw up their hands and say, ‘Ok, we let the girls go’?” Within days of landing in America, #BringBackOurGirls had vaulted onto the screens of some of the Obama administration’s most senior figures.

Rhodes and other officials for foreign policy, intelligence, and defence held hourlong Chibok sessions in the underground complex where the president had once live-monitored the killing of Osama bin Laden. Other meetings took place in the nearby gray-panelled Eisenhower Executive Office Building. Diplomats in West Africa tuned in on a video conference line, juggling the time difference.

The question was how the world’s most powerful government planned to help find and free the schoolgirls. With the hashtag migrating from Hollywood to Capitol Hill, it was inevitable that the kidnapping would appear on the president’s morning intelligence summary, compiled at the CIA’s Virginia headquarters. The president would want to know what policy options were available.

Formulating an answer fell to the National Security Council, the academics and intelligence officials who sketch out strategy for the White House. Al Qaeda allies in Africa had become a rising concern for the NSC, just as Twitter had also begun to shape its preoccupations.

Two of its staff had recently been appointed the NSC’s inaugural Twitter monitors, tasked with pasting five or six interesting or popular tweets into daily emails to relevant officials.

As those monitors watched the analytics on #BringBackOurGirls soar, the NSC staff began summoning top officials at defence, state, and other departments, to discuss the kidnapping. What could America do? Each department needed to reach into its capabilities and present assets it could offer.

The room was debating the deployment of more than a quarter of a billion dollars of sophisticated matériel, to look for teenagers held by a group that had never attacked the United States, on a mission ordered up by Twitter.

The Justice Department could send FBI agents with experience defusing hostage crises. The State Department had medics and psychologists it could fly in from neighbouring embassies to treat the girls upon their release.

But nobody around the table had anything approaching the resources of the Department of Defence, whose $614 billion discretionary budget for the preceding year was significantly larger than the entire Nigerian economy. Their answer to the problem was drones.

The US had satellites and propeller planes that could scan the Sambisa area. But for daylong flights of continuous intelligence gathering, they could use the “workhorse,” an RQ-4 Global Hawk drone, gunmetal gray with a bulbous head like a dolphin, which could surveil a South Korea–size acreage daily. A few weeks later, the US might be able to rotate in another drone, named the Predator

- A Wired report