While someone could technically have played the code as music, it would have sounded less like a tune and more like a cat walking across piano keys, says American saxophonist Merry Goldberg, who duped Russian spies with musical codes.

“I picked a note to start, and then I created the alphabet from there. Once you know it, it ends up being pretty easy to write things. I taught my friends on the trip the code, too,” saxophonist Goldberg, who led the musicians, says. “We used it in order to take in people’s addresses and other information we would need to find them. And we coded things while we were there so we would be able to take out some information about people and their efforts to emigrate, as well as details we hoped could help other people ask to leave.”

The US musicians got their bearings in Moscow before heading to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. There and on their next stop in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, they successfully met members of the Phantom Orchestra, many of whom spoke some English, and spent time getting to know each other, playing music together, and even staging small, impromptu concerts.

During eight days of travel, the musicians were tailed constantly by Soviet agents and were repeatedly stopped for questioning. Merryl Goldberg says that members of the Phantom Orchestra, all of whom faced similar treatment in their daily lives, gave her and her colleagues advice and encouragement. When the Americans would express concerns that their presence was endangering the activists, Goldberg says the Phantom Orchestra members were resolute about the importance of spending time together. She adds, though, that some of the activists were later arrested and even beaten, because of the interactions.

“On the second night, we were playing together and the KGB came in and everything got shut down. The electricity was turned off; it was a scary situation,” Goldberg says. “And yet, when we’re playing music no one can take away that sense of freedom and empowerment. Playing together and communicating with people through music is like nothing else. I was amazed by the strength it brought the people there. Music can be very comforting, but it also conveys a sense of feeling powerful.”

After their time in Yerevan, the American musicians had planned to go to Riga, the capital of Latvia, and then to Leningrad, now St Petersburg in Russia. Finally, they were set to stop in Paris before returning to the United States. Instead, they were stopped and questioned again.

The musicians were supposed to be placed under house arrest in Yerevan, but Goldberg says that Armenian officials bristled at the KGB intrusion and let them continue their trip. Eventually, though, the musicians were picked up and escorted back to Moscow, where Soviet agents confiscated their passports. Goldberg says the group was driven around Moscow for several hours, perhaps as a scare tactic, before finally being allowed to stay together in a dormitory room guarded by young Soviet men with machine guns.

“At that point, you’re thinking they’re going to take us to Siberia or something,” she says. “We were super freaked out. So, we kept playing music for each other that night. And we played a beloved Russian folk tune, but out of tune, to annoy the young soldier outside our door. It gave us a sense of humour and empowerment.”

Finally, officials said the group would be deported to Sweden. They were heavily guarded and brought to a plane that had come from Sweden and was going to return without passengers. While officials searched their possessions again before letting them on the plane, no one ever flagged the sheet music. Goldberg points out that she even got the film from her camera back, perhaps thanks to a sympathiser.

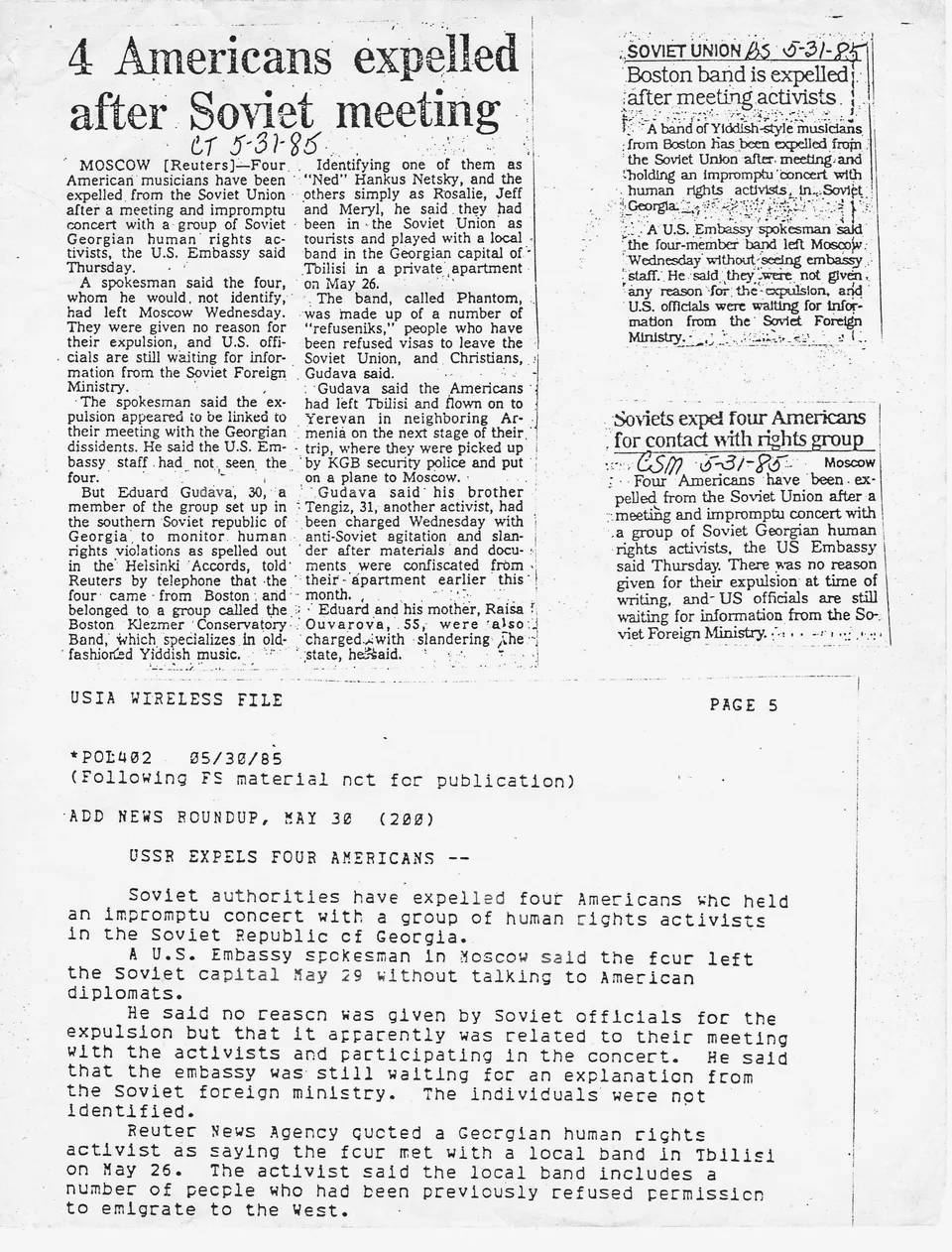

“They were given no reason for their expulsion, and US officials are still waiting for information from the Soviet Foreign Ministry,” Reuters reported in a wire about the situation on May 31, 1985. “The spokesman said the expulsion appeared to be linked to their meeting with … Georgian dissidents.”

Goldberg says that while she later learned that some of the Soviet activists faced consequences for the visit, some of the people the musicians met on the trip were eventually able to permanently leave the USSR. She notes that while her musical code wouldn’t have been very difficult to crack if someone were focused on it, the obfuscation served its purpose, making it both an elegant and harmonious encryption scheme.

- A Wired report