Wajir Resident Magistrate Vincent Mugendi has a lot to reckon with concerning Sexual and Gender Based Violence cases at the Wajir Law Courts.

“I have handled several cases of sexual offences since I was posted here two years ago with defilement being the most common among girls aged between 10 and 17 years,” says Mr Mugendi.

According to the magistrate, the high number of defilement cases in Wajir County and north-eastern Kenya in general can be attributed to early marriages among the Somalis, the predominant community occupying the region.

Kenyan law defines defilement as having carnal knowledge with a person under the age of 18 years. Most of the survivors who report the cases are school-girls while others are drop outs due to circumstances beyond their control.

Due to the high number of cases, several interest groups have launched an aggressive civic education and empowerment programme within the county.

Civil society and stakeholders like members of the Wajir Court Users Committees (CUCs) have made a big difference by reporting cases and ensuring prosecution of sexual offences in the county.

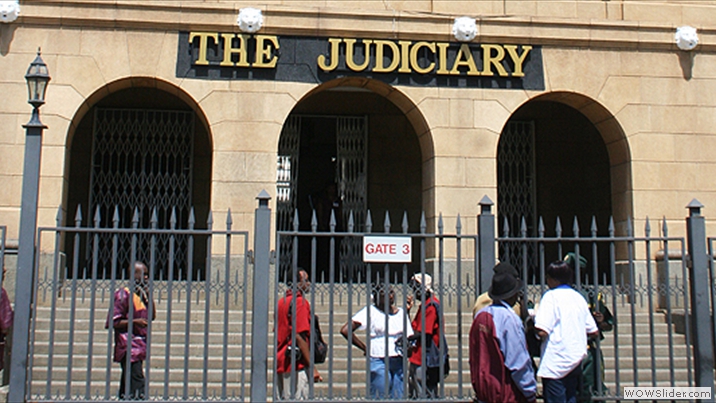

In the recent past Wajir County has been in the spotlight following focus by the media, paralegals, the police and judiciary creating more confidence and trust between all the stakeholders, members of the public and the affected community.

This has resulted in arrest and successful prosecution of suspected perpetrators leading to handing of deterrent sentences on conviction.

According to court records at the Wajir Magistrate’s Court, 20 sexual offence cases were recorded in 2017 out of which 18 were concluded while two are still pending.

As of June 2018, 16 sexual offence cases had been filed with seven having been concluded while nine are pending.

“The numbers have increased because of the confidence that the public has in the judiciary and greater awareness of the criminal justice system,” explains Mugendi.

Looking back to his two years in Wajir County, Mugendi says one of the most memorable case was one where an accused person defiled a 16-year-old. As a result of the incident the girl became pregnant and dropped out of school. In that particular case all the witnesses were cooperative.

They attended court on time and testified leading to expeditious conclusion of the matter. The accused person was jailed for 20 years.

The sentence was billed as a deterrence to the accused person and would-be offenders. The magistrate noted that the investigators did a good job in the case in procuring the witnesses and ensuring that all the exhibits including medical records, birth certificate and age assessment forms were in order.

Turning to rape cases, Mugendi said he has only handled three cases. One of them was of an elderly woman who was assaulted and raped by a young man. The perpetrator was later arrested and charged with the offence. He was convicted and sentenced to serve 10 years in jail.

Mugendi identified some of the challenges they face in dealing with sexual offence cases as lack of cooperation by the survivor, parents and witnesses to record statements, attend court and testify.

Mugendi gave an example of a case where proceedings stalled after the prosecutor informed the court that the P3 Form signed by a clinical officer could not be produced due to some technicalities and that the complainant had fled to neighbouring Somalia with her parents. The witnesses were also noted to be at large and could not be traced.

The case was mentioned severally and the investigating officer bonded the witnesses but it was all in vain. The magistrate later had to close the case and acquit the accused.

That case is not an exception but the norm in Wajir County where another big headache for stakeholders in the campaign against gender-based violence and violence against women and girls is the Maslahah, the Somali criminal justice system of alternative disputes resolutions.

The Maslahahsystem of alternative dispute resolution among the Somali often derailed conclusion of sexual assault cases in Wajir.

According to Mugendi, most sexual assault cases start well with the support and cooperation of the complainant and her parents, but things change as the case proceeds.

Often, the survivor, her parents and the clan change their mind after negotiating with the suspect in a maslahah and agreeing to settle matters out of court.

To address that challenge, the judiciary, through the Court Users Committee under chairman Amos Kiprop, who is the Wajir Senior Resident Magistrate, has been expediting sexual offence trials, especially of defilement.

Another strategy that has been successful has been to withhold bond or bail to the accused until the trial day after the minor and key witnesses have testified.

“So far I have found the Court Users Committee to be very active and vibrant. It has helped us to make progress, especially in sexual offence cases. Our conviction rate now stands at between 60 and 70 percent where there is no interference,” says Mugendi.

The Somali traditional justice system of Maslahah that is recognised as an alternative dispute resolution mechanism has seen the elders mediating in criminal offences such as sexual offences and murder, contrary to the laws of Kenya.

“This set up poses a challenge in sexual offences because women and girls are barred from attending such hearings. They are represented by their parents. If the parents protest, they are treated as hostile witnesses or outcasts,” explained Mugendi.