Regardless of government intentions, the problem with Nigeria failure to hammer out permanent peace agreements with insurgents is that the accords negotiated so far are badly flawed and amateurishly executed.

The running theme in all conflicts in Nigeria – as is the case elsewhere in Africa – equitable access to and distribution of natural resources. In multiple interviews with insurgents and mediators – be they local or international – the rebels and bandits lament about marginalisation and exclusion from the economy. The government does not listen; neither does it keep a record of the agreements reached.

These are some of the key issues getting in the way of workable deals:

Nothing in writing: There are usually no documents that outline terms and conditions, and no legal framework to guide implementation. That’s why, one bandit leader told The New Humanitarian, he considers them a “deal”, not an “agreement”: They are essentially transient and non-binding.

Lack of consultation: The peace deals are further weakened by the lack of involvement of farming communities. As a result, the farmers believe the interests of the aggressors are prioritised over the rights of the victims. The Yan Sakai – who farmers see as vital community defenders – complain that they hear about peace deals over the radio, just like everybody else.

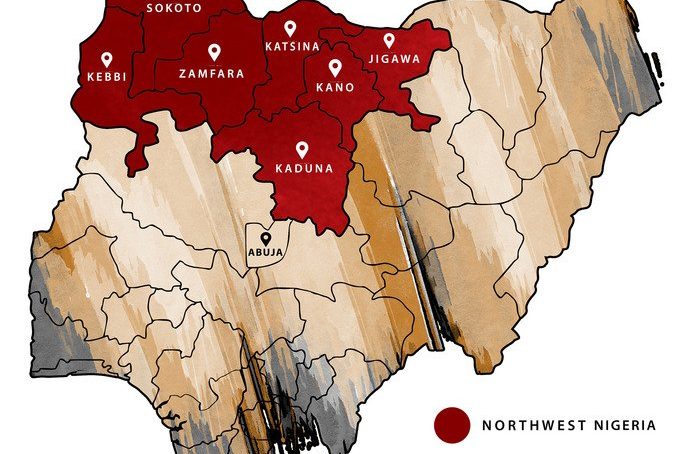

Bandit proliferation: It’s estimated that there are at least 80 major gangs operating in the northwest. No chain of command unites them, and they act in their own individual interests. This means a complicated series of negotiations are needed to bring them all on board – if that’s even possible.

Weapons are readily available in the northwest, flowing in from the jihadst conflict in the Sahel, or manufactured by local gunsmiths.

Hungry lieutenants: Negotiations are also complicated by the power dynamics within each gang. Deals are made with leaders, who have grown rich from banditry. They then need to sell the accord to their men, some of whom may not yet be ready to retire from a life of relatively easy money. Some deals have failed due to the overestimation of a warlord’s influence.

Guns galore: Media-friendly disarmament ceremonies don’t tell the full story. There are a lot of weapons in circulation, and it’s the village-based Yan Sakai that are at a disadvantage when it comes to surrendering them. The more mobile bandits can cache their weapons out of sight in the forests. And even though they are known to possess RPGs and anti-aircraft guns, those are usually not handed in – a lack of monitoring means they are likely to stay hidden.

No DDR: The lack of a formal disarmament, demobilisation, and rehabilitation (DRR) programme to support the reintegration of repentant bandits is also a challenge. Its absence compromises empowerment and psycho-social support programmes – which can leave surrendered bandits stranded and frustrated, vulnerable to re-recruitment.

Left and right hand: The lack of policy cohesion between the federal and state governments adds to the challenges of making peace. For instance, at the same time that Zamfara was offering an amnesty in 2018, the army was on an offensive, undermining the process.

The failure of the formally negotiated deals has seen the rise of hyper-local agreements between individual communities and the gangs, with villagers paying a tax in return for peace. In some areas, bandits now act as the law, settling local disputes and dispensing “justice”.

Smarter warfare: Nigeria must adopt a whole-of-government approach, with an emphasis on a military strategy that is holistic rather than piecemeal. In the immediate term, to establish peace, the government must first gain legitimacy by protecting the people.

Coordination: Peace deals alone are not a silver bullet in the fight against banditry: But they can be managed far better than the current ad hoc approaches: They need to be part of a “joined up” strategy that involves states and the federal government.

Incentives: A formal DDR programme needs to accompany any peace arrangement, similar to what is being implemented for surrendering jihadist fighters in the country’s northeast. Many of the bandits are young pastoralists without formal education. To leave the bush, they will need incentives, in the form of training and support.

No impunity: DDR should target the low-ranking foot soldiers, but the warlords must be held accountable for their actions. Given the sclerotic and frequently corrupt formal justice system, Nigeria should consider establishing special courts to try them.

Reparations: The success of any peace deal will depend on how the victims of the banditry are treated – including compensation for losses incurred during the conflict. For peace to be seen to be just, it needs to include reparations.

Reserves: To end pastoralist encroachment on farms – and farmer encroachment on grazing lands – reserves need to be gazetted, with water points, veterinary services, and schools also provided: an ongoing plea from pastoralists.

The government has drafted a National Livestock Transformation Plan that aims to curb the movement of cattle by encouraging pastoralists to switch to sedentary livestock production – more mechanisation and less transhumance. It’s a good start, but it is yet to be implemented – and faces financial, technical, and political challenges.

As this list of suggestions shows, for there to be any hope of ending the banditry in the long run, Nigeria must address the root causes of the conflict, and that requires far-reaching reforms in governance, and real accountability for all those associated with the insecurity.

- The New Humanitarian report