Some cases of sexual abuse in Malakal refugee camp in South Sudan are sometimes covered up by men paying money, proposing marriage, or giving the family a dowry, said Josephina James, assistant head for the women’s group in the camp that holds regular meetings to discuss such abuse and other concerns.

“Many humanitarians…caught many times in sexual exploitation in the Protection of Civilians (POC) sites during night patrol,” according to a report from the UN Population Fund sent to humanitarian organisations in Malakal on October 5, 2020.

“It’s the consequence of men with money,” the girl’s mother told reporters.

MSF said its worker was suspended for a month while it conducted an internal assessment. The man was then allowed to return to work. Leaders in the community – South Sudan’s society is largely patriarchal – took the side of the man, who accused the mother and girl of lying, the mother said.

“Our primary concern was for the wellbeing of the child, and MSF offered immediate medical care and psychological support,” Malika Ait, ethics and behaviour lead at MSF, told The New Humanitarian. “We then quickly opened an internal investigation, but we did not find any evidence to substantiate the allegations. Throughout the process, we provided support and communicated all steps to the family. If new information surfaces, MSF will immediately reopen an investigation into this case.”

Three of the victims who spoke with reporters said they were minors when the events occurred, between 2017 and 2021. One was the 15-year-old – 17 when reporters spoke to her in January – who said she was raped in 2019 by a local World Vision worker.

She said once the man was alone with her, he covered her mouth so she wouldn’t make noise during the rape. She said her economic circumstances were dire, so she continued having sex with him, four more times before she became pregnant. Feeling trapped and desperate, she tried to hang herself before finding the courage to leave the camp to seek a better life for herself and young daughter.

“Concerns have been raised by humanitarian NGO staff that a ‘turf war’ between UN agencies on the ground over leadership of PSEA initiatives and the Task Force has hampered effectiveness and coordination.”

“What went through my mind was that my mother had no work and no money, and so I decided to continue sleeping with him to help support the family,” she said, adding that the man refused to take any responsibility for her daughter.

Many women said they had sex because the men promised to marry them. Others said they were afraid that if they refused, the money and gifts that were often used to help their families – such as mobile phones – would stop.

“Based on an initial review, no allegation of this nature in this location has been made to us before,” World Vision Country Director Mesfin Loha said in a statement emailed to The New Humanitarian on July 12. “The investigation will be conducted with global oversight, given the seriousness of the claim that a staff member may have sexually abused a child.”

That investigation is still ongoing. The mother who said she was putting her eldest daughter on birth control also recalled her own pregnancy by a local WFP worker in 2019.

World Food Programme (WFP) told The New Humanitarian that since 2019 it had received six allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse against WFP staff in South Sudan – two in 2019, one in 2020, and three in 2021. It was unclear whether the case of the woman becoming pregnant was among them.

“Perpetrators are mostly by the humanitarians, UNMISS (the UN peacekeeping mission) and companies…some of them are already known to have HIV, hence spreading it in the community,” according to the report from the UN Population Fund sent to humanitarian organisations in Malakal on October 5, 2020.

“Investigations are ongoing and we are unable to comment on specific cases,” said Badejo, the country director and co-chair of the UN-led taskforce. She said there had been no cases against WFP staff in 2022.

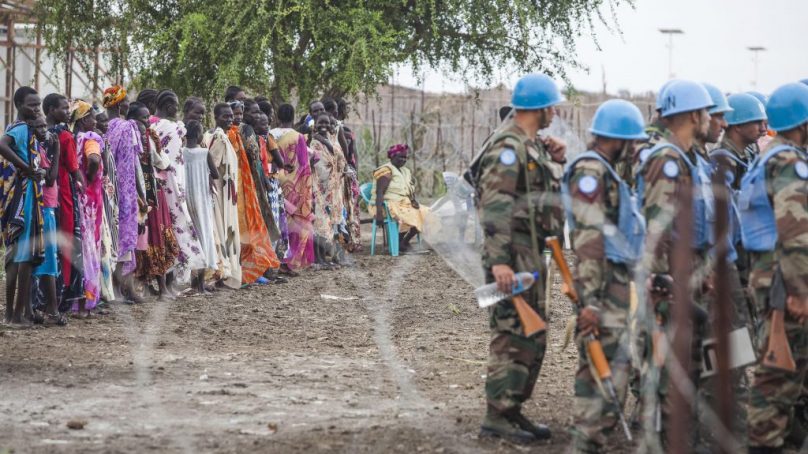

Tensions have been high for years in the camp, where locals compete for scarce jobs in the aid industry – a reality compounded by poverty, an outsized dependence on aid, and a lack of government investment in addressing the country’s many humanitarian problems.

In a recent UN report, South Sudan was ranked as having one of the lowest life expectancies in the world, at just 55 years. Some women who used to cultivate land before the war told The New Humanitarian and Al Jazeera they’re still too afraid to leave the camp for fear of being raped by soldiers or militias.

Those who are able to find work can spend 12 hours a day earning little more than $1, serving tea in shops, braiding hair or selling charcoal. Those who can’t find work are reliant on family members and the aid sector, making them even more vulnerable to sexual exploitation.

“UNMISS have refused to allow larger scale support to livelihoods in the PoC in recent years as they have articulated at field level that they believe the PoCs to be temporary in nature.”

One 25-year-old woman said she became pregnant in 2017 by a South Sudanese aid worker who said he worked for the UN’s migration agency, International Organization for Migration (IOM).

When the man abandoned her after she gave birth, she said she reported the case directly to IOM. But since a meeting in August 2021 with an IOM representative who took DNA samples, she said she hasn’t heard anything.

“They asked where and when I met him, how much he paid, and if [he was taking care of] the child,” she said. “But I’ve had no contact since then.”

Another woman, now 21, said that when she was 16, a man who said he worked for IOM offered her necklaces and gifts in exchange for sex – items her father, who worked at a school in the camp, couldn’t afford. She said he cut all ties months after she gave birth to his child.

“I forced myself to have sex with him so he wouldn’t question why he was giving me gifts and money,” said the woman.

IOM, which said it had received 11 allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation against its workers in Malakal since 2017, said two of them involved paternity claims but that it couldn’t comment on the women who spoke to reporters, due to having insufficient information.

IOM also adheres to strict policies to protect complainants when dealing with paternity complaints, according to IOM spokesperson Safa Msehli. In two cases, in 2021 and 2022, one allegation was closed for lack of evidence, while the other was referred for potential disciplinary action, Msehli said, adding that sexual relations between UN staff and beneficiaries are prohibited.

*In both of the paternity claims, IOM staff voluntarily submitted DNA samples, and tests were negative, IOM said.

- The New Humanitarian report