Fresh fruit and vegetables, sold commercially in the camps’ markets, are largely unaffordable for most Western Sahara refugees. Cheaper, processed food is available, but that has contributed to a “double burden of malnutrition”, which includes obesity among women and under-nutrition in children.

Thirty-one-year-old Fatimalo Mustapha Sayed manages a community vegetable garden in Camp El Aaiún, approximately 30 minutes’ drive from Camp Smara, says the refugees health is compromised by quantity and quality of availability.

Sayed’s vegetable project – funded by a UK charity – sells the harvest to the Polisario, which distributes it among the camp population. It also donates a portion to local charities, including a school for children with special needs, helping to fill gaps left by aid agencies.

But while her days are busy tending to the garden, it’s difficult to avoid the topic of war. Sayed’s brother is also a soldier, and she is the daughter of Bachir Mustapha Sayed, a senior Polisario official and the brother of El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed, who co-founded the organisation in 1976 before being killed in combat later that year.

“Thirty years with no war really impacted [us],” Bachir Mustapha Sayed says, referring to a 1991 ceasefire agreement. “Morocco kept maintaining their forces, and they improved their technologies. So we are disadvantaged. But… we have motivated people.”

Thirty-six-year-old Fadili Malainin was among the thousands of men to enlist in the Sahrawi People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) back in November 2020 when the Polisario relaunched its armed struggle. Military service is voluntary, but many soldiers – veterans and new recruits – have been eager to join the fight.

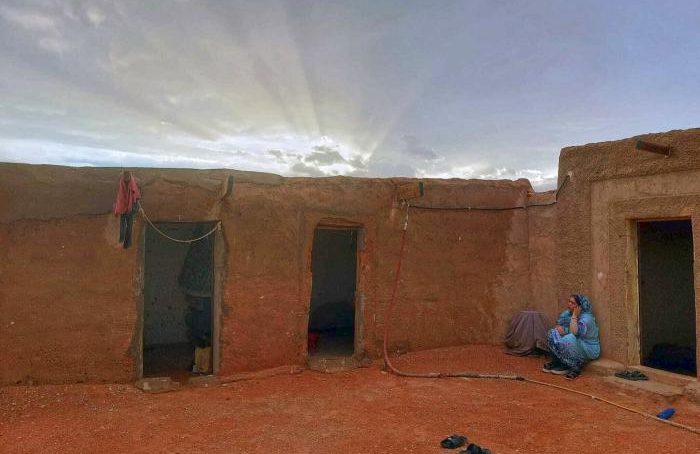

Malainin lives in Camp Boujdour – the smallest of the five camps – in a home he shares with his wife, Fatimetu, and their toddler son, Bachir. Malainin spends several months a year working at a restaurant in Spain to earn money to send home to his family, while Fatimetu works as a music teacher for primary school children in Boujdour.

Together, they earn enough to enjoy simple luxuries like air conditioning. UNHCR supplies water, shelter and cooking gas. The Algerian government provides electricity and internet connectivity to all the Sahrawi camps.

Algeria, one of Polisario’s few international backers, also supplies military equipment, including kamikaze drones from Iran. Since the return to war, tensions with Morocco have been particularly high, culminating in Algiers cutting diplomatic ties with Rabat in August 2021.

SPLA soldiers serve months at a time on the frontlines, returning to the camps only to receive medical treatment or to stock up on supplies.

“I know it looks like we’re living here more permanently,” said Malainin, gesturing around their modest living room as he prepared traditional Sahrawi tea over hot coals. “But we’re just doing it to make ourselves more comfortable. It’s not about staying here.”

Malainin explained that, for him, the camp can never be home – returning to a free Western Sahara is the dream he is fighting for.

Malainin served three months in the SPLA in 2022 and will return to the frontlines later this year. Asked if she worried about her husband’s safety, Fatimetu paused as he calmly interjected: “I would give up my life for my family to be free.”

For women like Fatimetu, who care for large extended families in the camps, there’s a constant fear of losing loved ones. The Sahrawi Ministry of Defence releases daily communiques detailing the attacks from both sides, and Fatimetu says several of her close friends and neighbours have been killed since fighting resumed. She says the children she teaches are also traumatised by the war.

“It’s hard for us as a society to express our feelings, so, for the children, it comes out in all sorts of ways,” she told The New Humanitarian. “There was a boy who got in a terrible fight during class, and we later found out that his brother had recently died in the war.”

While the Polisario Front has reported heavy fighting in recent weeks, Morocco refuses to acknowledge the war in what it refers to as its “southern provinces”.

The SPLA operates under a significant military disadvantage. Much of its equipment dates from the 1970s and 1980s, when Libya was a major supplier. Morocco’s armed forces, on the other hand, are trained in modern warfare and Western-equipped.

“It’s hard for us as a society to express our feelings, so, for the children, it comes out in all sorts of ways.”

Morocco has also acquired tens of millions of dollars’ worth of Israeli-made drones after normalising ties with Israel in December 2020. This was part of a deal that saw the United States, under then-president Donald Trump, become the first country in the world to recognise Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Speaking in an interview just days after her brother was nearly killed, Mohamed-Lamin, whose three other brothers and stepfather are also fighting on the front line, said she has no option but to be hopeful for the future.

“Hope doesn’t guarantee if you are going to reach something, but it makes you keep going,” she said.

- The New Humanitarian report