A message in the visitors’ book in Maralal National Museum serves as a reminder that Kenya President Uhuru Kenyatta knows where he was conceived: the detention house where his father had been transferred rehabilitation as they colonial government prepared him to take over the reins power at independence.

He is now in his last 11 months before he hands over the baton to the next president. He celebrates his sixtieth birthday next month. He remembers the story of his conception through the visitors’ book.

President Uhuru Kenyatta visited Kenyatta House, where he was conceived as his father Jomo Kenyatta waited to be released from detention. On his visit to the facility, he noted in the visitors’ book in 2007: “Conceived in this house in the Year of Lord 1961; a pleasure to be back using my own two feet.”

As I enter the gate to the iconic compound, I am welcomed by giant blue myrtle cactus on both sides of the driveway leading to a white three-bedroom bungalow surrounded by trees where Kenya’s independence was brokered.

The 59-year-old building stands firm on a 20-acre piece of forest land on a hillside overlooking Maralal town, Samburu County.

Kenyatta House – as it is referred to – is where Kenya’s first president Mzee Jomo Kenyatta was partly detained by the colonial government from April 1, 1960 to October 1961.

At the door entrance, John Rigano, the curator informs me that there are charges one has to pay before taking a tour of the house.

Kenyan adults are charged Sh100 and children Sh50, while other East Africans part with Sh400 and their children pay Sh200. Other foreigners pay Sh500 and children bellow age 16 years of age pay Sh250.

With a receipt in hand after settling the required fee, Rigano says that one of the reasons why Kenyatta was airlifted from Lodwar to Maralal was because fellow detainees had planned to assassinate him after learning that he was holding independence negotiations with colonialists.

He explained that those behind the assassination plot discredited Kenyatta as an incapable, senile and a leader unto darkness to discredit him. They were unanimous that Jomo Kenyatta was incapable steering independence talks.

During the prison transfer, a senior colonial administrator had to vacate to a smaller government building to pave way for Kenyatta.

“A few days after arriving here, Jomo held an international press conference outside this house to clear the air about the allegations against him that he was incapable, senile and a leader of darkness,” Rigano says.

Rigano clarifies that Kenyatta was not detained at the Maralal house but it is where Kenya’s independence was brokered after the colonialists chose Kenyatta to steer the talks over then political heavyweights Oginga Odinga, Tom Mboya, Ronald Ngala and Masinde Muliro.

According to the curator, a white settler by the name Sir Michael Blundell acted as a go between Jomo and the colonial government and it is believed that he facilitated Kenyatta’s move from Lodwar to Maralal.

“Blundell recommended Kenyatta over Ronald Ngala who was seen as only popular to his small (Luo) ethnic group. Odinga had Russian ties and battled for supremacy with Mboya in Luo land, therefore leaving Kenyatta who he believed would unite all the blocs headed by Odinga, Ngala, Mboya, Masinde Muliro and Daniel Moi,” the curator explains.

Blundell came to Kenya when he was 18 and later served as member of the colonial Legislative Council (Legco) and twice as minister for agriculture. He owned huge tracts of land in Solai in the present Nakuru County. In the countdown to Kenya’s independence, he defied white settlers and led a movement of moderates in support of Africans’ agitation for internal self-rule.

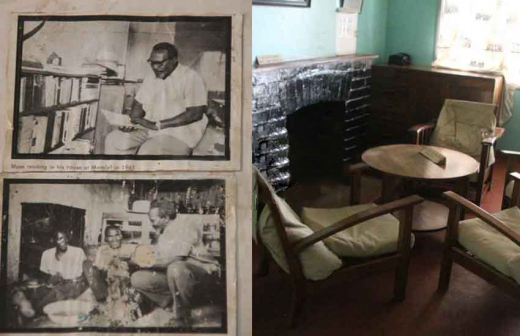

In the sitting room, besides the fireplace, there are four wooden couches covered with converse pillows with a round wooden table at the middle and a four-seater dining table set besides a window next to the kitchen door.

Prominently sitting at the corner of the sitting room next to the chimney is a black extension landline telephone equipped only with a receiver and a turning knob. It was operated from the colonial District Administration office. Its orange label, which reads ‘MILL 5, EXTN 2, JOMO KENYATTA’ is still intact.

There are a number of Kenyatta’s photos on the wall some taken with friends he made in Maralal during his short stay towards the end of his detention since 1953 for alleged involvement with Mau Solia freedom fighters.

“He was allowed to walk to Maralal to town to mend his shoes and do some shopping in the company of two armed policemen. Since he had many admirers, he was not allowed to speak to more than ten people at a time,” the curator says.

Rigano reveals further that one of the two policemen who guarded Kenyatta was Kipchoge Keino who moved with Kenyatta to State House and later won Kenya’s first Olympic gold medal.

During his stay in Maralal, his wife, Mama Ngina Kenyatta and their two children Christine Wambui (now Christina Pratt) and Jane Njeri were allowed to live with him and even started their elementary schooling at Maralal DEB primary school.

After getting all this information, while standing, you are not allowed to seat on the furniture because they need to be preserved for future generations. Rigano leads me to the guest bedroom where Kenyatta’s visitors slept.

Before seeing him, his visitors had to get clearance from the colonial authorities. Among the visitors were: Oginga Odinga, Tom Mboya, Ronald Ngala, Daniel Moi, Mbiyu Koinange, Masinde Muliro, Margaret Kenyatta (daughter) and John Keen.

Everything in this house is well preserved and appears as it was. Though the house has been repainted twice by the National Museums of Kenya, the curator is only allowed to paint red oxide on the floor and wash the premises on a daily basis.

In the master bedroom we find a wooden study desk facing the window and from it one can see the semi-hilly terrain of Maralal town.

“On a clear morning, one can see the snow-capped apex of Mt Kenya. It is on this hardwood desk that the founding father edited his book Facing Mount Kenya that was first published in 1938,” Rigano tells me.

Apart from a wardrobe and a wooden chest there is a dressing-table with a full-length mirror with a charcoal iron box atop it. The two-by-six feet bed is made of wood and metal and a sisal mattress rests on the silver springs.

“Is it true that Uhuru Kenyatta was conceived in this room,” I ask Rigano. He smiles and opens a visitor’s book with impeccable accuracy to a page where the President signed and wrote when he visited the house.

It reads, “Conceived in this house in the year of Lord 1961; a pleasure to be back using my own two feet.”

The writing in black ink signed by President Uhuru Kenyatta himself on July 1, 2007 confirms that this house indeed bears important connection to the country’s independence and its former and current leadership.

We next tour the children’s bedroom, which has two beds, next to them is a flushable toilet and a bathroom equipped with a bathtub. Rigano tells me that water to the house has been disconnected to avoid spillage in the house and corrosion of the iron pipes.

“We try to keep this place as original as possible as you can see there is no electricity inside the house apart from outside for security purposes,” he points out.

The kitchen comprises of a firewood oven that could barbecue meat, bake bread, cook and at the same time warm the house and heat water for bathing.

The house which receives about 2,000 visitors annually was gazetted as a national monument by the National Museums of Kenya in 1977.

– A Tell report/ Robert Gitau