Rising obesity rates have set off alarm bells for years. In 2018, 42 per cent of US adults were obese, up from about 30 per cent two decades earlier, and prevalence is climbing rapidly in other countries, as well. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines obesity as having a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30, a calculation made by dividing weight in kilogrammes by the square of height in meters.

Although the value of BMI has been questioned, it remains a common metric in medicine and scientific studies.

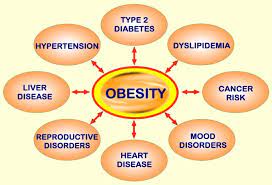

Scientists have long explored links between obesity and health problems. For example, according to a 2020 study in Obesity Science and Practice of almost three million UK adults tracked for an average of 11 years, people with a BMI between 30 and 35 had a risk of type two diabetes five times higher than that of people whose BMI was defined as normal.

For a BMI of 40 to 45, the risk was 12 times higher. Obesity is also associated with a higher risk of heart disease, stroke, sleep apnoea, certain cancers and osteoarthritis.

Differences in where and how fat is stored can affect underlying health. Excess visceral fat, deep in the abdomen, is associated with more inflammation and fat build-up in certain organs (inset), and is more harmful than subcutaneous fat, which is stored under the skin and can promote health.

There is no agreed-on definition of metabolic health, but one research team’s definition, applied to two large cohorts, showed that it becomes less common with obesity but is still present.

Yet many people with obesity have healthy cholesterol and blood glucose levels, whereas many lean people do not. “You go to an obesity clinic, [where] people weigh 120 kilogrammes, 140 kilogrammes. Some have problems and some don’t,” says Antonio Vidal-Puig, who studies and treats metabolic disease at Cambridge.

Conversely, he notes, patients who weigh 70 or 80 kilogrammes might be insulin resistant and have diabetes. Trends also vary by ethnicity. People of South Asian ancestry “develop diabetes without the levels of obesity in other populations,” Farooqi says. “We’re not all the same.”

Philipp Scherer’s mice offered a clue to the variation: Their fat was stored under the skin rather than in muscle or in organs such as the liver. That pattern aligned with what obesity researchers and doctors have observed in people. Scherer is a researcher at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Large population studies have shown that people with excessive visceral fat, deep in the abdomen, are at higher risk of health problems than people with high volumes of subcutaneous fat, under the skin of the thighs, arms, and backside.

When someone has high visceral fat, “that’s when metabolic disease occurs,” says Bernard Zinman, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto. Visceral fat generates inflammatory molecules, and imaging studies have shown it’s associated with fat build-up in the liver, pancreas, and muscle.

By contrast, subcutaneous fat can nurture good health, serving as a store of energy and helping cushion muscle and bones. Some evidence indicates people with ailments such as heart failure or cancer fare better if they are modestly overweight than if they are lean.

In 2005, a CDC and National Cancer Institute research team reported that overall, people who were overweight but not obese had slightly lower mortality rates than people whose weight qualified as normal. “Fat is our friend, and we need it,” Scherer says. “If you don’t have adipose tissue, you really are in big trouble.”

Subcutaneous fat is also a safety valve: Without such a zone for stashing extra fat deposits, they travel to the visceral region. Rare disorders called lipodystrophy syndromes illustrate this vividly. Affected people cannot accumulate subcutaneous fat and appear thin, yet they develop diabetes and fatty liver disease.

“Do you have all these walk-in closets” for healthy fat storage, Zinman asks, “or do you live in a condo where you have just one cupboard? Some people have tremendous ability to store calories, and others don’t.”

Another clue about the value of fat storage capacity – and subcutaneous fat itself – comes from a class of diabetes drugs called thiazolidinediones introduced in the late 1990s. Intriguingly, while reducing blood glucose levels they also caused patients to gain weight.

Several studies reported that the drugs help convert fat precursor cells into mature fat cells in subcutaneous regions. Patients added fat subcutaneously, which appeared to reduce inflammation and improve the body’s response to insulin.

“It’s not how fat you are, it’s what you do with it that counts,” Vidal-Puig titled a commentary he co-wrote in 2008. At the same time, Vidal-Puig expresses a quandary he and colleagues face: He is reluctant to use the term MHO, which he worries could mislead people into thinking, “it’s OK to be obese.”

“We are not saying that,” he says. Rather, some people “are healthy because they are resilient to obesity.” Vidal-Puig wants to stick to the science of that resilience by exploring how obesity can coexist with measures of health. “We are explaining how it works.”

- A Knowable Magazine report