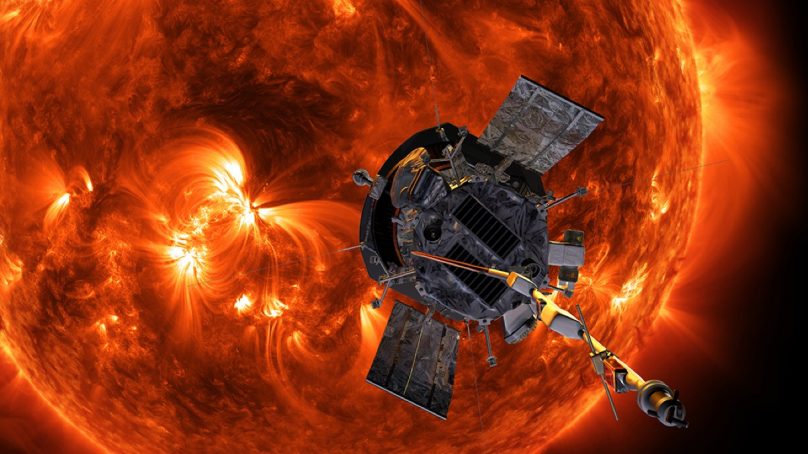

A NASA spacecraft has entered a previously unexplored region of the Solar System – the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. The long-awaited milestone, which was reached in April but announced on 14 December, is a major accomplishment for the Parker Solar Probe, a craft that is flying closer to the Sun than any mission in history.

“We have finally arrived,” said Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, located at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC. “Humanity has touched the Sun.”

She and other team members spoke during a press conference at this week’s American Geophysical Union meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana. A paper describing the findings appears this week in Physical Review Letters.

In many ways, the Parker Solar Probe is a counterpoint to NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft. In 2012, Voyager One travelled so far from the Sun that it became the first mission to leave the region of space dominated by the solar wind – the energetic flood of particles coming from the Sun.

By contrast, the Parker probe is travelling ever closer to the heart of the Solar System, flying head-on into the solar wind and our star’s atmosphere. With this new front-row seat, scientists can explore some of the biggest unanswered questions about the Sun, such as how it generates the solar wind and how its corona gets heated to temperatures more extreme than those on the Sun’s surface.

“This is a huge milestone,” says Craig DeForest, a solar physicist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, who is not involved in the mission. Flying into the solar corona represents “one of the last great unknowns,” he says.

The Parker probe crossed into the Sun’s atmosphere at 09:33 universal time on April 28. Mission scientists needed several months to download and analyse the data the spacecraft had collected, and to be sure that it had indeed crossed the much-anticipated boundary, known as the Alfvén surface.

This surface marks the interface between the Sun’s atmosphere and an outer region of space dominated by the solar wind. Swedish physicist Hannes Alfvén proposed the underlying theory behind the boundary in a paper published in Nature in 19422, and scientists have been looking for it ever since.

Total solar eclipse with the sun’s inner corona (atmosphere) visible around the disc of the moon. But it took the $1.5-billion Parker Solar Probe to finally get there. Since its launch in 2018, it has been orbiting the Sun: with each pass, it loops ever closer to the solar surface.

A carbon-composite heat shield protects its instruments from temperatures that will eventually soar to 1,370 °C. The spacecraft crossed the Alfvén boundary when it was around 14 million kilometres, or just under 20 solar radii, from the Sun’s surface. That’s about where team members had expected to find the interface, says Nour Raouafi, the mission’s project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

Some researchers had speculated that the boundary would be rather ‘fuzzy’ – but, instead, it was sharp and wrinkly. The spacecraft’s trajectory took it into the corona for nearly five hours and then back out; and it might have briefly crossed into the corona twice more. Inside the corona, the solar wind speed and plasma densities dropped, suggesting the boundary had indeed been crossed.

“We are learning new things that we did not have access to before,” Raouafi says.

As it crossed the Alfvén surface, the Parker probe flew through a ‘pseudostreamer’ of electrically charged material, inside which conditions were quieter than the roiling environment outside of it. While inside the corona, the spacecraft also studied unusual kinks in the magnetic field of the solar wind, known as switchbacks.

Scientists already knew about switchbacks, but the probe’s data have enabled the researchers to trace where the switchbacks come from, all the way down to the solar surface.

Knowing how such features form on the Sun, and how they influence the solar wind and other eruptions of charged particles, will help people on Earth to prepare for disruptive space weather, such as solar storms that can knock out satellite communications.

The discoveries will also help researchers to understand the forces that power stars other than the Sun, said Kelly Korreck, a solar physicist at NASA’s headquarters, at the press conference.

The Parker Solar Probe ultimately aims to make 24 close passes of the Sun. It crossed the Alfvén surface on the eighth of those fly-bys, and might have done so again during its ninth pass in November – a manoeuvre for which the data have not yet been fully downloaded and analysed.

The mission’s closest approach is scheduled for 2025, when it will be only 6.2 million kilometres from the solar surface, well within the orbit of Mercury. Each visit will continue to reveal new information about processes in the corona, said Justin Kasper, a solar physicist and deputy chief technology officer at BWX Technologies in Washington DC, who works on the Parker probe.

“Being this close to the Sun is allowing us to make really interesting and new connections we wouldn’t be able to do from afar,” he said.

- A Nature report